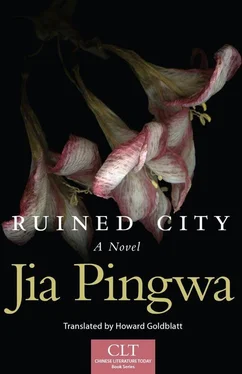

“You wrote the letters, but now you’re referring to her, the woman. It was fake, but it’s become real to you. If you had it published, I’m sure people would gossip. Haven’t you learned your lesson from the Jing Xueyin incident? I hate to say it, but it seems you’ve lost your head since Zhong’s death.”

“You don’t know what you’re talking about,” Zhuang retorted impatiently.

“You’re right, I don’t. I don’t know a thing. But I’m afraid you know too much.”

Tang was on her way over with the ginger tea, and when she heard their harsh voices, she coughed and waited until they fell silent before she walked in.

Zhuang’s head still ached on the day of the viewing, so he took a painkiller before leaving for the memorial site. An unusually large number of people showed up. Wreaths filled the site and overflowed all the way outside. When the memorial was over, Zhuang insisted on accompanying the coffin to the crematorium. It took several people to stop him. One of them who knew massage techniques worked on Zhuang’s head on the steps outside. Li Hongwen walked up.

“There’s such a long line at the crematorium,” he said, “he may have to wait until the day after tomorrow. They told us to put his body in the freezer for now.”

“That won’t do,” Zhuang said. “Folks in the countryside can’t be at peace until the body is in the ground, and for us in the city, it has to go in the crematorium. So many people came today that it would be terrible if the cremation wasn’t carried out. Besides, you know your colleagues at the Department of Culture very well. If the cremation isn’t done today, who will take care of it later?”

“That’s what I thought. I kept telling them that, but all they said was, ‘Go line up.’ You’re famous; why don’t you go talk to them?”

Meng Yunfang came running over from the crematorium. “Problem solved,” he said.

Zhuang asked how he had managed to talk the people around.

“I saw a red sign saying ‘Special treatment for intellectuals.’ You see, the government is promoting respect for knowledge and talent. This place knows to respect intellectuals.”

Saying that he hadn’t seen the sign, Li complimented Meng on his sharp eyes. The three of them went over and said that Zhong Weixian was a highly regarded intellectual who should be moved ahead of others.

“Intellectual?” the man in charge said, “Can you prove it?”

“He was editor-in-chief of Xijing Magazine ,” Zhuang said.

“Got any proof?”

“What proof? Do you mean you have to bring an ID for a person to be cremated? Can’t we vouch for him?”

“This is Zhuang Zhidie you’re talking to,” Li said.

“What does he do? There are one-point-one billion people in China, and I can’t remember all their names. What office do you work for?”

“You mean you don’t know who Zhuang Zhidie is? He’s with the Writers’ Association,” Li said.

“Riders’ Association? There are intellectuals among riders? We only accept IDs for high-ranking positions, like professors or chief engineers.”

“It doesn’t matter what I ride, but the deceased did have a high-ranking position. He was a senior ‘editor,’ not a ‘creditor,’” Zhuang said.

“You’ve got more of a temper than me! I need proof.”

They could only stare wide-eyed. Zhuang told Li to get the head of the Department of Culture, who came to tell the man that the deceased was truly an editor, a high-ranking intellectual who died before he got his ID. He would vouch for him, leaving his name and phone number for the man to check. The man told him to write a memo. When that was done, he asked for the seal from the Assessment Office, saying that since there was only one crematorium in Xijing, people sometimes posed as leading cadres or intellectuals when there were too many bodies waiting to be cremated.

“I’ve sent too many like that into the fire. You can’t put anything over on me, because I know what the Assessment Office seal looks like.”

Left with no choice, Li Hongwen and Gou Dahai raced off in the department head’s car to have the memo stamped with the Assessment Office seal. About an hour later, they came back happily, one of them waving a red plastic certificate holder. “The Assessment Office made an exception and issued the certificate as soon as they heard about the problem.”

Zhuang walked up to get the certificate to show the man, who wordlessly wheeled Zhong’s body to the front and pushed it into the furnace with a long hooked pole. Zhuang gritted his teeth as he watched, then abruptly tossed the little red pamphlet into the furnace before spinning around and walking out of the memorial auditorium, getting on his motor scooter, and tearing down the street without a word to anyone.

. . .

Zhuang did not feel like seeing anyone for two weeks. Tang Wan’er sent several notes with her pigeon; he caught the pigeon and took off the notes, but sent the bird back without a response. But his plan to stay home was disrupted by so many visitors that he got on his motor scooter to roam the lowland redevelopment area early each morning after drinking milk from the cow. He wasn’t really sure why he was there, but he watched a group of old-timers squatting on a dirt mound chatting, accompanied by the roar of a bulldozer razing crumbling walls. They talked about the lowland, where there had been several brothels, one of which was called the Duck Pit. The prostitutes at the Duck Pit were cheaper than those from Yingchun Pavilion, who could sing and dance. Visitors to the Duck Pit were usually horse grooms, colliers from Mount Zhongnan, or manual laborers from north of the Wei River transporting touch paper, porcelain ware, cotton, and tobacco on the backs of mules. The women were so cheap they could be bought with a bowl of wontons, and the men could satisfy their needs and warm their feet in the women’s arms all night long. The old-timers also talked about a cotton fluffer who used to live around there somewhere and pounded used cotton with a club, his back bent all day. He was so poor he couldn’t afford a hat, so he wrapped a colorful headscarf of his wife’s around his head, leaving the tips of his ears to freeze, to the point that they shriveled up. But he seemed quite content. He would bang the strings on the cotton-fluffing frame while his feet tapped along with the rhythm his hand created. The man and his wife were the perfect match: a cracked wok with a dented ladle. She had been with a performing troupe from the midwestern loess, playing the clappers, which was known as banging the pigskin. Once she was married, she stopped doing that, but the moment her husband started fluffing cotton, she sang a piece from The Butterfly Lovers in a creaky voice: “Squatting to pee, the women write essays; standing to pee, the men wet walls like dogs.” The old-timers also gossiped about the Lu Family Spicy Noodle Shop, a small place renowned for its pure Yaozhou peppers. Old Man Lu was a hunchback who had produced a beautiful daughter who was later taken by an army officer as his concubine. Her father got rich and stopped selling noodles; instead he brewed a pot of tea early every morning to sip at his lane entrance. For some reason the officer’s concubine came home one day and hanged herself from the red toon tree in the backyard, a great loss of face for the father, who then sold the house and moved away. Three more families moved in, one after the other, but within two years the wives had all hanged themselves. Zhuang listened to them without going up to ask for details or inquiring whether there were other unusual events or people in the area; instead, he was curious about why these old-timers were so interested in these stories. Why did they appear so attached to the place now that the redevelopment was underway, though they might have complained about the lack of progress before? Later, when they started a game of mahjong, he saw them shuffle the tiles and swat their heads and faces; one of them grumbled, “What’s going on here? Why am I itchy all over? How did my skin become so delicate in my old age? I’ll have to buy a scratcher tomorrow.” Zhuang was amused, but then he began to itch; there were no mosquitos around, and the itch was worse than a mosquito bite, creating such a burning pain that he decided to go home. He went out again the next day; there were noticeably fewer people on the street, and the faces of nearly all of them were covered with scarves, like people in Beijing protecting themselves against a sandstorm in March. He stood there and watched with a smile until he was itching all over. He rolled up his sleeve and saw patches of red bumps on his arms. When he took a closer look, he discovered two white specks on his arm, like dandruff, but the spots itched and ached as the dandruff turned red and three-dimensional. Some kind of insect, he saw. He took off, scratching himself all the way home. Niu Yueqing, who had come home early, blocked him at the door and told him to take off everything but his underwear before coming in. Once he was inside, she disinfected him in a tub.

Читать дальше

![Matthew Vincent - [you] Ruined It for Everyone!](/books/216429/matthew-vincent-you-ruined-it-for-everyone-thumb.webp)