Lately, everything that came out of her mouth sounded cryptic.

I told her how to start the motor because I needed two hands to do it. She pulled the string a few times really wimpy, so I told her to really pull and on that last turn she pulled with all this anger and exhaust spilled out from the motor. We were ready to go.

“Are you sure you want to do this?” I asked, really trying to say Can you handle this on your own, because I’m kinda scared that I won’t be able to jump in to help if shit goes awry.

She said, “I want to learn,” and we set off together as she kept saying, “This is going to be fun.”

Trapped on a sailboat together heading out to the Long Island Sound and I started thinking that maybe this was nuts. What were we going to talk about for all these hours? Maybe she’d be okay with staying silent except for when we had to move the sail. Because this was feeling kind of therapeutic right now and my physical therapist had told me to find therapeutic things to do.

I put my bad hand in the water, letting it drag off the side to try to feel things, while staring down into the water.

The wind changed direction and I told her to change the tack. I had to keep it simple, even though I’d explained some sailing terms to her when we got on the boat. It was almost hilarious, Cheryl and I sailing.

CHERYL

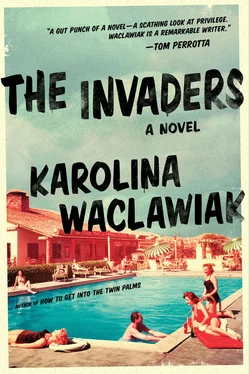

TO TAKE THE BOAT out without even asking, without even mentioning to Jeffrey what we were doing, felt like we were making a run for it. The view of the homes from the water was something to marvel at. A row of muted tones faced out, with the slimmest breaks in between each house, the lawns blending into each other in one manicured line. Nearly every home had a flagpole with not only the American flag flying, but small, narrow yacht club flags as well. No one shied away from their nautical convictions here. When Teddy and I boarded Jeffrey’s boat, I tried to ignore the Joanne in big letters staring back at me. Jeffrey and Teddy’s grief was an infection that would not budge. The fear of loss kept them from really trying with anyone else. I had taken that burden on myself, though. I was in the shadow of a dead woman, a flawed, beloved woman here. There were remnants of her everywhere: long-forgotten boxes in the garage, half-finished airplane bottles of liquor jammed in the back of drawers and cabinets, a monogrammed washcloth stuffed behind our daily-use set in the linen closet. She was everywhere and nowhere. Sometimes I wondered if things would have been different if I had met Jeffrey well after her death rather than having it infect our marriage during its honeymoon stage. It made us feel guilty for our happiness. It made us feel watched and scrutinized.

“Tack left.”

We both leaned down under the sail, and I swung it over us, and we sat on the opposite side.

“You’re much easier to sail with than your father.”

“Oh yeah, he takes the joy out of anything.”

“He’s not all bad.”

“Say it like you mean it, Cheryl,” Teddy said, laughing.

We stared at the waves, the water bright and shiny in the distance, and the islands that dotted the landscape.

“Where do you want to go?” I asked.

We both stared out at the stretch of water and then Teddy said, “I don’t know. Far away. As far as we can go.”

I looked down deep into the water and wondered what was under us, the murky gray-green water. The jellyfish weren’t out yet, floating like implants along the face of the water. It was still safe to put your hands in.

“Whatever you want.”

He leaned his hand into the water and we sailed forward and I felt in control for the first time in a long time. We sailed away from the houses, the long fence being erected, Lori’s sand, and the club.

“What a beautiful day. We’re so lucky,” I said.

“Speak for yourself,” Teddy said. “Speak for yourself.” He stared down at his hand as the water slid through his fingers.

“I’m sorry,” I said.

“It’s not your fault,” he said. “It’s just the way things happen sometimes.” If I don’t say anything now, I thought, he might never know. “Did you ever sail before you met my dad?” he asked.

“Once, and we capsized,” I said.

“That’s the worst. My dad used to capsize us just to see how well I fared under pressure.”

“How could your mother let him do that?”

Teddy laughed and said, “She was always jumping around the shore, pissed. She loved to sail, though. That’s where I get it from. That, and you know, she thought it was a super important part of networking. Starting in kindergarten with golf and yachting and private schools and shit. Get in line with your kind.”

“I wish I’d had that when I was your age,” I said.

“You grew up here, too, didn’t you?” he asked.

I told him that I had grown up not far from here, in the northeastern corner of the state, where farms and chickens outnumbered people. It was amazing that a few dozen miles could create such a distance in lives. The shoreline was a dream and in the summers we’d pack up and drive to Hammonasset, the one public beach we could find, and pretend we belonged by the water. We’d stare down the shore toward the private beaches and wonder how you could own something like that, the sand and the water.

He asked me who the “we” was and, trapped on this boat, I felt like I was telling him too much.

He pressed me further, asking where they were. I didn’t know, I told him. We had lost touch. It was not untrue. I hadn’t spoken to my sisters in so many years. We had detached from one another somewhere along the way and never thought to realign, come together, remember who we were or where we came from. We had been too busy surviving to feel any sense of closeness from our shared history. I wondered if they thought about my mother, reached out to her, or forgave her for anything.

“All this,” Teddy said, waving toward the houses and club, “doesn’t amount to much if you don’t care or try, you know? You gotta want to put on your armor of seersucker, get out there, and make the connections. I don’t really care, so the tennis lessons and sending me to Kent and Dartmouth were probably worthless.”

“Those things can never be taken away from you. You’re privileged.”

Teddy looked at me with disgust and said, “If I was, I’d still have my mom.”

We sat quietly and stared out at the water.

“I’m sorry,” he said after a while.

“I’m sorry you don’t have your mother anymore,” I said.

The boat hit a wave and rocked violently. Teddy scrambled to grab hold of the loose ropes of the mast.

“It’s fine,” he said. “Calm down. Tack right.”

I leaped forward, barely missing Teddy as we slid under the mast.

“You did a beautiful job cleaning the boat, Teddy,” I said, fingering the top of the letter J on the back of the boat.

“She would be sick to see how he’s let it go to waste.”

“He just can’t look at it,” I said.

“Then sell it.” He turned toward me and said it again, “Then sell it.”

“He knows you would never speak to him again.”

“Let it go or keep it and take care of it. Don’t make her an eyesore. Something to be whispered about and mocked. Fuck him.”

“He’s trying,” I said.

“Yeah, with you, me, and everyone. Really well. Where the fuck is he, anyway?”

“Grief hits people in different ways,” I said.

“How long is it supposed to feel like this? Forever? I can’t take forever .”

I didn’t know how to answer him. Jeffrey couldn’t shake it, I could see it. The guilt radiated off him. She wouldn ’ t be drinking so much all the time if… It always came back to if they had just been better. The fact that she died so visibly and tragically — her drunken fall off the docks in the middle of the night — brought the community together and kept me out. They martyred her without all the facts. Sometimes I wondered if it was a conscious decision or the accident everyone believed it to be. I never expected Jeffrey to get over his love for her. Or maybe I did, at first, naively.

Читать дальше