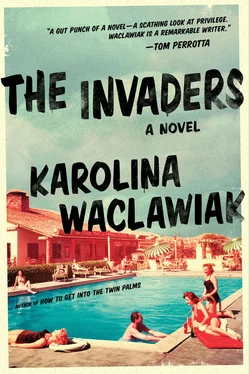

Karolina Waclawiak

The Invaders

SO LONG AS I PERCEIVE THE WORLD AS HOSTILE,

I REMAIN LINKED TO IT: I AM NOT CRAZY.

— ROLAND BARTHES, A LOVER’S DISCOURSE

CHERYL

WHEN JEFFREY’S FIRST WIFE told me he had a voracious appetite for women, I assumed she was just trying to be vindictive. Now, as I walked up and down the beach on my insomnia prowl, I tried not to think about all the things he had loved about her. The list seemed short to me, but it was always long to him. Why couldn’t you love her like that when she was around? I had asked once. He had no idea where the love had gone then, but it was revived after she died. Perhaps that was when I should have left, but I kept hoping we could get back to the before-time — when we felt lucky to be near each other. On mornings like this the sunrise would come up over the Long Island Sound and the neighborhood streets would be quiet and empty. Each beach house had an incredible view of the winding Connecticut shoreline, and if you squinted, you could see Long Island in the distance. Four a.m. would hit and I would find myself walking by windows trying to see what everyone was up to, hoping to see a blue wash of TV screens and peering around for something indecent. But the houses would be dark and quiet, everyone long asleep. It was the kind of neighborhood that was full of children, their soccer balls and plastic bats lingering in the streets, toy trucks lost in the manicured lawns of American flag-adorned clapboard homes. I looked down at a dirt-caked Barbie doll with kite string wrapped around her plastic arms and wondered if all these children were destined to become troubled teenagers who were shipped off to college with a sigh of relief, as we had done with Jeffrey’s son, Teddy, three years before.

Without people, Little Neck Cove was one of the most breathtaking places I’d ever seen. I’d ignore the No Trespassing signs and climb down neighbors’ stairs onto their beaches to walk and unwind before Jeffrey woke up. I’d pace the rocks and the beach, looking for shells, mating horseshoe crabs, or seagulls floating through the dawn sky. The beach was covered in smooth, flat stones, hidden quartz and oddly shaped bloodstones. I’d pick them up and inspect the strangest ones, dropping them into my pocket one by one. There was always snapped pieces of seashells and kaleidoscope sea glass all for the taking. These small objects that flipped and swirled along the ribbed floor of the sea would outlast us all. The soft, small waves made a hypnotic sound that would relax me into bliss. The sky would turn gray first, then light blue and finally explode with oranges and yellows. There was nothing to obscure my view here, just sky as far as I could see. I could sit on the beach for hours, listening with my eyes closed, sometimes falling asleep completely. It was the only place I didn’t feel shut in, claustrophobic, unwelcome.

Hours before the humidity became unbearable, I would watch the fishermen out on the jagged rocks that jutted out into the sound, their lines glistening in the early morning glow. I knew they had been there all night, drinking and fishing as the waves lapped around them. One, an old man with a shaggy terrier, had come every summer since I met Jeffrey. He drove a beat-up truck with a raccoon tail on the antenna. Seeing him always meant the start of the summer for me. Lately, though, there were more men wandering around than usual. There was talk that we had made some online list for the best place to clam and fish. People were angry at the intrusion.

We were far away enough from New York to feel like we were in a different world, but close enough to have successful commuter husbands. In the evenings, I’d see a row of pursed-lipped wives idling their cars in the parking lot of the commuter rail station, watching their bar-car-riding husbands stagger off the train. The Connecticut shoreline was full of small towns like ours, each with an old Congregational church and a large town green at its center. Homes with plaques stating their Revolutionary age stood next to tasteful shops and cafés along Main Street. And along the water were hidden coves and snug blocks of beachside cottages. People from New York would grab them as soon as they came on the market, trying to turn this swath of Connecticut into the Vineyard or the Cape.

I passed the anchor of our little neighborhood, the Little Neck Cove Yacht & Country Club, just as the grinding daily cacophony of lawn mowers began. The decorations from last night’s Gatsby party were still up. Jeffrey and I had always gone when we first got together — looking silly in a seersucker suit and a flapper dress, but it was fun. We hadn’t gone in years. That’s what happens: tiny adjustments and contractions to your needs because things are fun and you believe they will never stop being that way. We used to go to all the themed parties and find ourselves making out on the beach, my dress all sparkly in the moonlight. We didn’t care who saw us then. We had always been the last couple dancing, full of life, our hands all over each other, sweat beading everywhere. Now I had to stanch the flow of happy memories to survive our current state of indifference toward each other. If I brushed against him, he seemed startled. I had taken the laughing and groping and desire that seemed endless for granted.

After I watched the sun rise this particular morning, I didn’t feel like sneaking back into my bed, pretending I was waking up alongside Jeffrey. He didn’t appreciate my attempts at normalcy and never asked where I had been when he woke up to an empty bed anyway. It was as if he was somehow grateful for my absence.

I decided to keep walking to the neighborhood’s nature trail. Built into the saltwater marshland of tall cattails, the trail traversed inlets and thick labyrinthine channels connected to the next hidden cove of homes. It was Connecticut postcard-perfect here, full of painted turtles and tiny crabs and unexpected sprays of beach roses. Whenever the tall grass was flattened back after a storm, I could see the teenager-forged trails into the hidden parts of the marsh. I’d follow the trails until they led me into a small grove with beer cans and burned-out wood piles. I’d collect the cans and clean off the wax from tree stumps, trying to erase the damage created by the late-night parties. I wanted to find them in midswing during one of my walks, see who was lusting after whom, feel what it was like to be young again, nervous and hopeful, but I only ever found the remnants of their drunken joy.

• • •

I was enjoying the bright sparkle of the water, training my binoculars on the hatching birds’ nest beds staked high above the sea grass. The hiss of locusts and summer beetles filled the air, a clucking that I missed all winter long. As the sun rose, the humidity felt like a bath and I was already soaked through my shirt. I had a thin, small bird book that Jeffrey had given me in my back pocket. Now was the time when the plover birthings were in full swing and it was exhilarating. Their call notes, plaintive, bell-like whistles, filled the air around me. It was a sound unlike any other and I preferred it to humans talking. The whistles flitting around me made me feel calm yet alive. These birds were unencumbered. They just lived and flew, and most of all, they didn’t betray. I tried to follow their calls and considered going off the bridge to walk along the shore, a no-no in the bird-sanctuary rule book. I wanted a closer look, so I looped one leg over the rope of the boardwalk and looked around to make sure no one was watching. Then I heard a moan, almost a groan really, and looked down. Three feet below me were two legs with sneakers and an arm feverishly moving. I pulled my leg up and backed away from the edge of the boardwalk, not wanting to disturb anything. I didn’t want to be caught watching. I didn’t want a confrontation.

Читать дальше