To say nothing of the ones who walked in and saw Alice and just lost it.

Once, at the end of a catch-up coffee, Jeremy said he and his significant other were praying for Alice. Oliver answered with the same Grinchy statements he used when Blaine, breezing in with magazines, casually asked whether he needed anything. “If you want to actually be helpful, contact the bone marrow donor registry.” Sometimes he launched into a public service lecture: At the very least you’d increase the odds for someone out there .

This day, Alice was unfortunate enough to be around. Placing her hand on Jeremy’s arm, she did her best to short-circuit Oliver’s vitriol.

“Thank you. Any good thoughts have to help.”

—

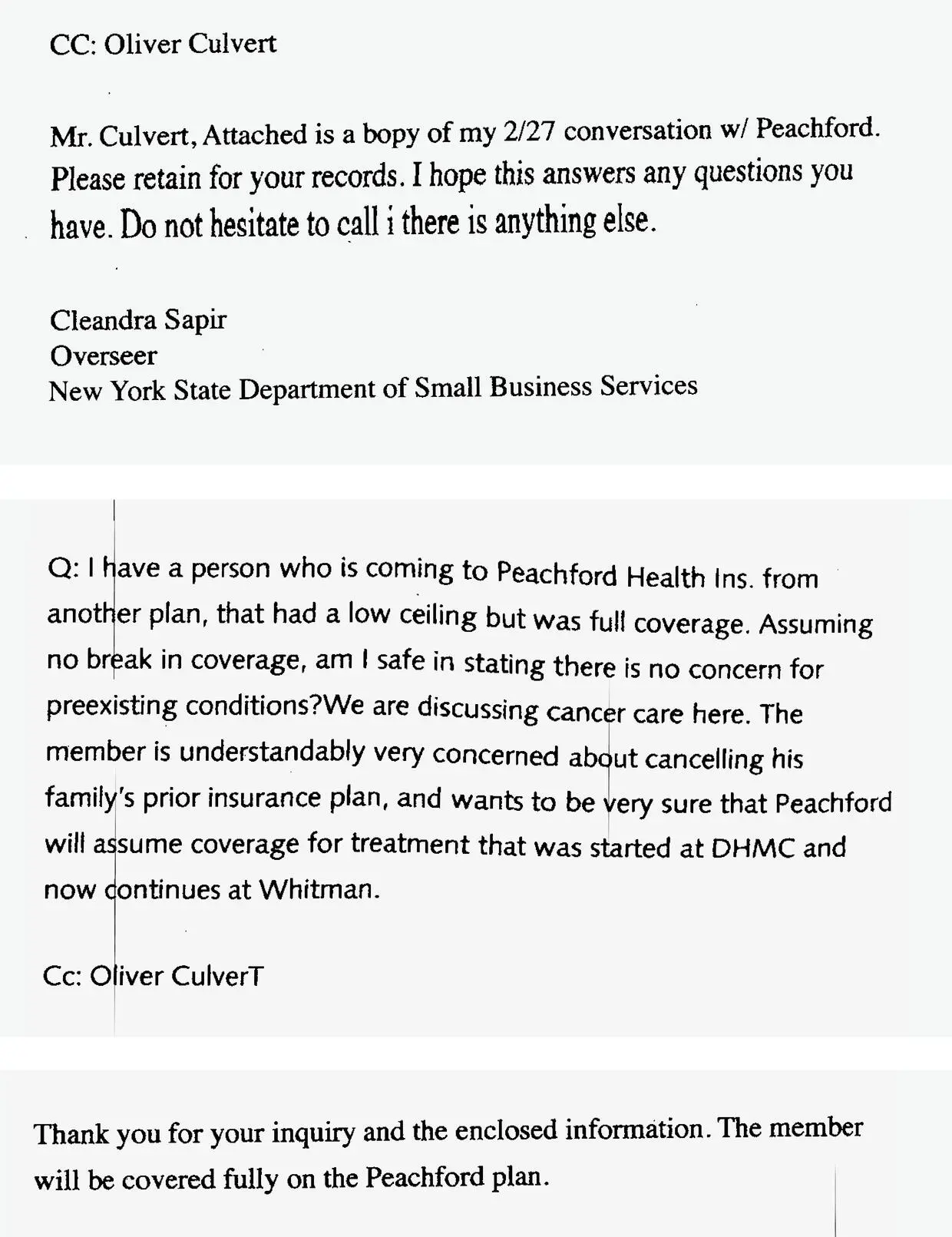

Alice was still asleep; Oliver picked up the phone on the third ring. “Yo?” The line went dead. Later that afternoon, he was on hold to ask a question to an official at the small business department, and switched over to the call waiting, and promptly became a punch line yet again, hung up on once more.

When he checked their messages, he began noticing those quick clicks, the line going dead as soon as the answering machine started its greeting. Oliver checked the times of the calls — always that low middle of the afternoon, perfect for taking a break from your responsibilities, that dull stretch when you’re just trying to get through.

Why don’t your friends say anything to me? he asked Alice.

She assured him it wasn’t them. She’d mentioned it. Nobody knew a thing.

“What about your little troubadour? From the hallway — weren’t you counseling him on the phone for a while?”

Did she flinch? No. Her breathing stayed even. “I don’t think so. He’s harmless. It has to be a crank call,” Alice continued. “Teenagers get a number and won’t let up. Believe me, I’m annoyed, too.”

Oliver nodded. He’d given this enough attention. And there were bigger fish already on his plate.

—

“Something I want to run past you, Ruggs, if that’s all right.”

Forgoing small talk, or even a greeting, Oliver started in.

“This lawyer who’s been helping me, well, he pointed me to this city program. It offers small businesses employee health insurance. But get this, spouses are eligible. And in-network costs don’t have a ceiling.” Oliver waited. The silence implied consent. “Thing is, we switch Generii onto this plan, it’s going to cost. Which is kind of why I’m calling. We have some money in reserve, but there’s still a ways before the demo’s up and running. Fucking who knows when we hit market. Meaning, you know, joining this plan? On the one hand, it gets Alice that policy and that’s big. But for the business, purely from that perspective, ah—”

“Who do you need me to kill?” Ruggles answered.

When it was Jonathan’s turn to hear the plea, he said, “It’s nice of you to ask, Oli. But really?”

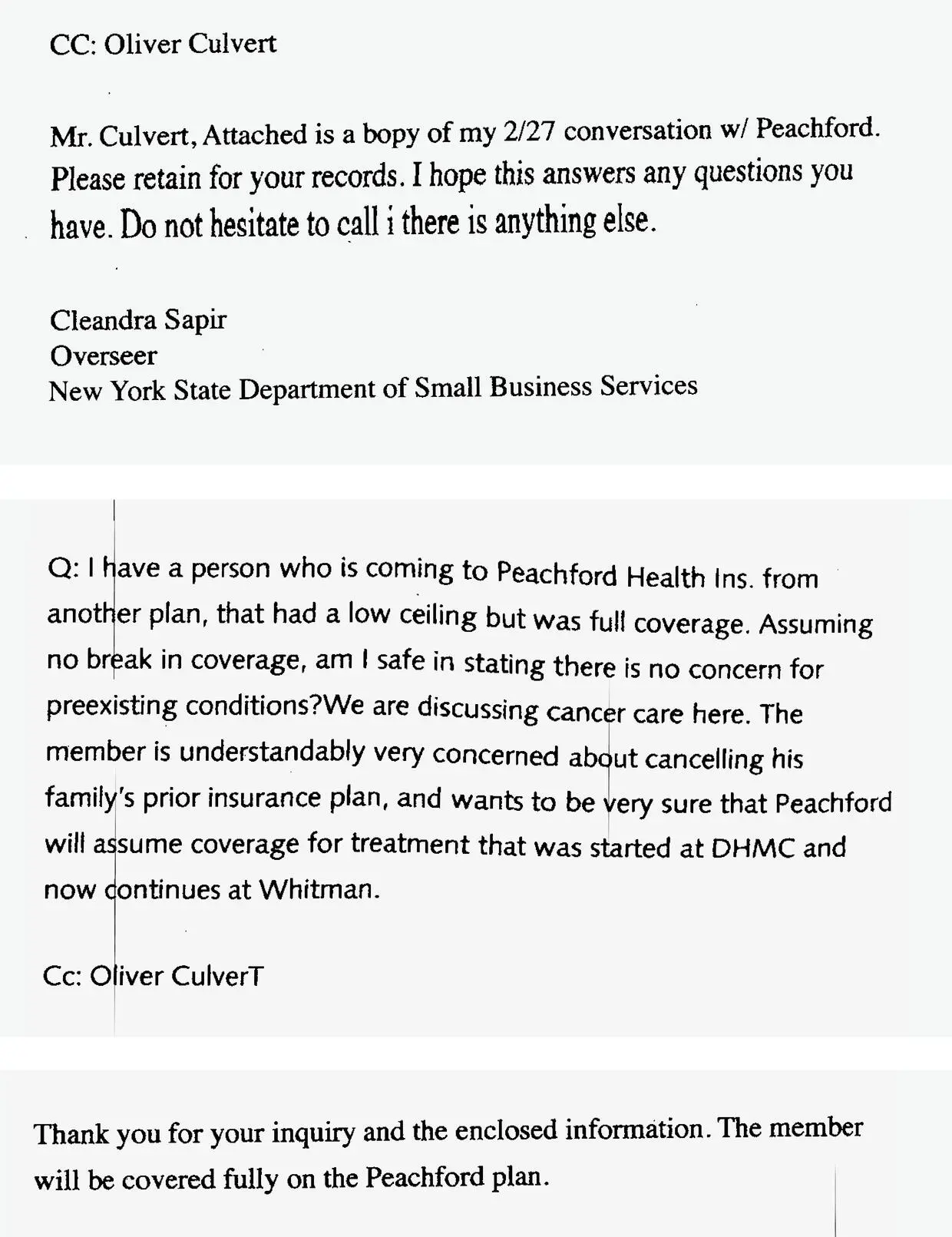

So the fax machine belched, pages curling out, dropped from off the tray, onto the floor.

Like that. The weight of a planet. The member will be covered fully.

They allowed themselves to breathe. He recounted for her the sequence of fax exchanges, suspense escalating through his progression, Alice clasping his hand in both of hers at the moment of truth. Cackling, she drew him to her, touched the front of her head to his, held her hand on the back of his neck.

He made copies of the fax, as Blauner had said he should for important papers. Put these copies in separate safe places.

Of course there were more fires on the horizon — aside from just figuring out which bills could wait on for another month.

First was basic and unavoidable: the chief goddamn programmer behind this whole Generii thing remained indisposed, distracted, or missing in action for prolonged stretches.

Nobody with a heart would begrudge Oliver, or question his priorities, but it was still an issue, their original touchstone deadline long in the rearview.

Second problem: while Alice was getting her consolidation, the Brow had taken over the workspace, programming round the clock, crashing on the couch. It hadn’t reached the level of young Bill Gates — who, according to legend, used to fall asleep at the terminal when writing the first Windows code, then jolt awake and, without a hiccup, pick back up where he’d left off. But the Brow was basically chained to a desktop. And progress was being made; everyone remained hopeful. At the same time, Alice was home now, and her immune system wasn’t safe around the floating biological circus of unwashed programmer detritus.

Meanwhile, every minute those terminals were vacant meant wasted time, the pissing away of definitively finite resources.

An afternoon’s search uncovered a building around the corner. On the third floor, just above a storied meat locker, a small office was available. According to lore, twice a week for twenty-five years, a navy vet staggered up the death-trap stairwell and unpacked from his leather satchel needles, inks. Rumor had it he’d once beaten a murder rap in military court, which was why he called his three machines kits or rigs, as opposed to guns, growling to those who made the mistake: “Guns kill people. That’s the diff.” Cops, firefighters, and paramedics were foremost among his steady drip of visitors, who treated the city’s ordinance against tattooing with as much regard as its laws against smoking dope on the sidewalk.

The space was cramped, dusty, hot as a furnace, its windows flooding with light from dawn to dusk. It smelled like an assignation spot for hoboes. When Oliver asked, the realtor explained that the tattoo artist had passed away at his desk, and baked in the sunlight until his assistant finally came and discovered the corpse. Workers below had thought that one of their deliveries had been left out of the freezer.

So there was a new monthly rent, fumigation and cleaning costs, and new phone lines for a new Internet connection that would allow their computers to receive streams of information at an updated, previously unheard-of rate of 54,000 bits per second. He’d also need new secondary lines for faxes and calls so their fragile new state-of-the-art Internet connection didn’t get interrupted. Electricity bills would spike. Throw in some new desks and ergonomic chairs because he employed a bunch of entitled, whining bitches. Clothespins for all offended noses.

“My fucking cousin wants to be an installation artist. What the fuck that is, I got no clue,” Ruggles told him. “Kid got into RISD though. He’s struggling but hanging in there. Know why?”

Oliver started to answer; Ruggles held up his finger.

“Kid lives on rice and air. Steals paper from Kinko’s. The whole starving artist thing. Any baby bird, like our fledgling venture here, you need as little overhead as possible, capisce?”

Oliver apologized. “Right.”

His friend’s pupils widened: Do you really?

Ruggles had spent an afternoon during Alice’s consolidation at her bedside, deftly goading her into a conversation about the upcoming Oscars. He had delivered, hands down, the best toast at Oliver’s wedding.

Indeed, Elliot Ruggleschmierr had been key in Oliver’s life since orientation weekend of their freshman year, a pair of mismatched majors joined together by their encyclopedic knowledge of Star Trek trivia. But as Oliver waited for his old roomie to render a verdict, he couldn’t tell whether Ruggles might have taken umbrage at the possibility that all he cared about was money.

Maybe Ruggles had been touched by the fiscal concerns that Oliver was showing for the company, even in the middle of this ordeal? Was he simply calculating added costs?

Читать дальше