“Well, you’ve gotten so much praise, and she’s gotten a lot of criticism.”

“No she hasn’t,” I snapped back. “What criticism?”

“Well, the Bridge review and the one in the L.A. Times and then the blogs. And Martin’s got a review coming out today or tomorrow.”

I’d avoided learning that much about movie criticism; I didn’t even know what blogs she meant. But I did know that Ben Martin was the movie critic for the Star and that his review would be more important than any other.

“A bad one?” I asked.

But she just waved her hand vaguely, took another bite of tofu.

“Look, I’m not trying to say anything bad about the movie. I loved it. I’m just curious about how you’re handling the response as a couple.”

I wondered if they’d taught her this in her journalism classes, what to say if a subject got upset. I wondered if she’d thought that I’d be easy to interview, that I’d give up all kinds of dirt because I didn’t know any better. I promised myself I’d disappoint her.

“We don’t care what other people say about us,” I said. “Especially Sophie. The only important thing is making good movies and making each other happy.”

“So she’s supportive of your career, even if it doesn’t involve her?”

The idea that I would do movies without Sophie really hadn’t occurred to me until right then. I had no idea how she’d feel about that. But I was on a good track now, and I was going to stay on it.

“Of course,” I said. “We’re behind each other a hundred percent. We don’t have any choice. We’re each other’s everything.”

On the train ride home, I was proud of myself for what I’d said. I’d tell Sophie, and she’d be proud too. We’d both do a lot more interviews, I thought, and we’d keep saying the same things, and eventually we’d have no choice but to live by them.

At the motel Sophie had her suitcase out on the bed. She was carefully folding her clothes into it.

“Where are you going?” I asked, smiling even though I was already scared. “Maine?”

“No,” she said.

She folded up a boy’s button-down shirt that I recognized from our old days together.

“Sophie,” I asked, “what’s going on?”

“The Star review came out,” she said. She pointed to her laptop.

I’d been so worried about what to say to Lucy that I’d almost forgotten the review. But once I started reading it, I couldn’t look away. Ben Martin started by talking about Sophie’s career, calling her movies “deeply unsentimental.” Then he said, “There’s a fine line between unsentimental and outright unfeeling, and Isabella has crossed it.” I had the thought that I should stop, go comfort Sophie, tell her that what that asshole said didn’t matter. But I kept reading. He talked about Sophie’s “fundamental flaw.” He compared her to a robot. He said the only good thing about the movie was me.

I still think that after I read the review, there was a chance for us. If I’d told myself it was bullshit, if I’d slammed the laptop shut, and looked at Sophie with all the love and respect I’d felt when we were first together, and gone to her and told her she was so much better than he said, and believed it, I think we would’ve come through. But instead I believed him. Not completely — I didn’t think Sophie was a no-talent loser who would never make a good film again. But looking back, I did think the movie was drab and ugly. And I did think I was the best thing about it. It felt good to let myself believe that — after letting Sophie convince me that she was the only one who could make a movie good, that sometimes she had hurt me to do it and that had to be okay, I wanted to feel like actually I was the one her movies couldn’t live without.

So I did go to her and rub her shoulder and kiss her cheek, but all I said to her was, “What do you care what that guy thinks?”

“I care if it’s true,” she said. Her voice was flat and dull.

“Of course it isn’t true,” I said, but I didn’t sell the line, and when she turned to me, she saw I didn’t really believe it.

“I’m going to go stay with my brother for a while,” she said.

Sophie didn’t talk about Robbie much, but still I’d always been jealous of him. She’d once said he was the only person she could talk to without feeling bad about herself — when I asked her if I made her feel bad about herself she said no, but it sounded forced.

“How long are you going for?” I asked.

She shrugged. She was doing something that always scared me, moving like she had almost no strength in her body, like she was about to fall right down on the floor.

“A month,” she said, “maybe longer.”

“A month?” I almost yelled. “I thought we were going to look for a place together.”

“I thought so too,” she said. “I thought that would help. But I don’t think so now.”

I hated when she talked like that, like she was so mysterious. I thought she was being petty, so I was petty right back.

“You’re so mad that I got a good review and you didn’t that you don’t want to live with me anymore? Maybe you need to grow the fuck up.”

She didn’t flinch, just sat down on the bed and looked up at me.

“You know,” she said, “when I met Veronica, I knew she was fragile in all the right places. I knew I could break her down. But I couldn’t do that to you again. Once you came on, I just had to let it be your movie.”

“That’s the only way you know how to make a movie?” I asked. “By making other people miserable?”

She just gave me a sad laugh and one of those huge shrugs I used to find so charming. But I’d given up my life for her and I didn’t have any sympathy.

“Fine,” I said. “Go rest somewhere else. Get the fuck out of here.”

“I’m sorry,” she said, standing. I turned to face away from her, like a little kid.

“Jump off a fucking bridge,” I told her.

I didn’t feel guilty when I said it or when I heard her close the door on her way out. I was sure I would see her again.

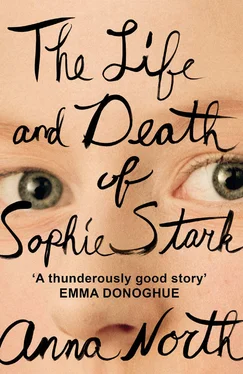

A Queen Dethroned

By Benjamin Martin

The story of Queen Isabella of Castile — the persecution by power-hungry elders, the secret marriage to her first love, the transformation into ruthless monarch and early architect of imperialism — is long overdue for the biopic treatment. Sophie Stark, whose films have long focused on strong, unusual women, would seem like the ideal director to steer this story away from period schlock and toward the truly revelatory. She has accomplished the former, but not the latter.

Stark has always been a deeply unsentimental filmmaker. But there’s a fine line between unsentimental and outright unfeeling, and Isabella has crossed it.

The film looks like it was made by a robot. Stark has always had an acute visual sense, so there must be a reason she chooses to set Isabella in modern-day New York City and to show us the flat, ugly interiors of motel rooms and apartments and industrial Brooklyn at its most dull and gray. It’s impossible to determine, however, what that reason might be. Isabella was reportedly conceived as a much larger-budget film than it eventually became, and the more expensive version might have been more entertaining — maybe Stark’s sensibility would have subverted the tired conventions of corsets and throne rooms. Here it’s just removed them, replacing them with nothing.

Читать дальше