“That’s good,” I said. “He should. It’s great.”

“Thanks. Most people seem to like the movie, actually. It almost makes it harder.”

And before I could ask her what she meant by harder she was out of her seat, throwing away her empty cup, buttoning that expensive coat.

I wanted to say something about how much she meant to me and how I hoped we could see each other again, but she took my hand and shook it firmly and said, “I’ll e-mail you,” and walked out onto the street.

THE NEXT FEW WEEKS were kind of hazy. Both Lauren and my therapist asked if I was feeling worse — my therapist even said I should think about taking medication. But I wasn’t worse. It was true that I hadn’t gotten to ask Sophie any of the questions I wanted to ask her, and I was disappointed about that. But more than anything I just felt quiet, like when you first go outside on a winter day and let the cold start waking you up. Lauren and I went to Emma’s dance recital and even though I’d been bored and fidgety at every other recital I’d ever been to, this time I just watched. I went for another drive out to the quarry, but I didn’t stop there. I drove on deep into the country so I could look at all the old houses and the women outside planting bulbs in the thawing ground and the mixed-breed dogs, and when it got too dark to see anymore, I drove home.

A week after I got back from Chicago I got an e-mail from Sophie. The subject line was “I thought you might like this,” and there was no text in the body, but there was a video attached. I waited until Lauren was asleep to watch it, and there I was, spinning and spinning. The video was shaky; Sophie must still have been learning then. But she kept zooming in on my face, like that was the important part. I was spinning so fast at first that it was blurry, but as I slowed down, right before I charged at her, she got a good, clear shot, and there I was, red-faced and crazy with joy. I paused the video and looked at my face a long time. I could see how someone might have loved me like that, and I didn’t know if I could ever look that way again, but I thought I could try. “Thank you,” I wrote back, and then I turned the computer off and got into bed.

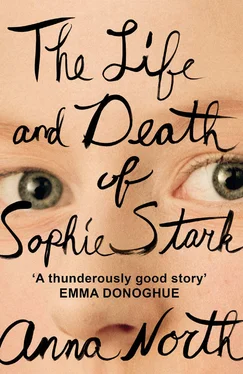

Into the Woods with Sophie Stark

By Benjamin Martin

There are some directors who care a lot about whether you have seen their movies. I know this because as a young reporter for the Burnell College Mongoose , I had the bizarre good fortune to meet indie film god William Cockburn, all of whose films I happened to have seen. On learning this he took me under his wing and spoke only to me the entire evening, causing my already overinflated 21-year-old ego to swell nearly to bursting. (I did not tell him that I found all but one of his movies tired and obvious, and indeed this fact faded from my memory as he praised my intelligence and discernment.) Sophie Stark, whose hotly anticipated second feature, Woods , will be released in March, is not one of these directors. When I told her I was pretty sure I’d seen everything she’d ever directed, including the short film Daniel and the music video she directed for singer-songwriter Jacob O’Hare, she said only, “Good.”

When I asked her to elaborate, she said, “Well, you’re writing a thing about me, so it’s good you’ve seen my movies.”

We were talking in the small but light-filled living room of the Brooklyn apartment she shares with O’Hare, now her husband. Stark is 28, but she moved with the economy of an old person, or one conserving energy. She wore a light gray dress with loose sleeves like wings, and she perched on the edge of the couch as we talked, carefully picking clean a chicken leg. She seemed by turns oblivious and hyperaware of my presence — when I asked to use the bathroom, she ignored me, but when I paused on the way back to examine a photograph on the wall behind her, she turned around to stare at me. The shot was of a young boy eating an ice cream sandwich, and it had a certain quality I associate with Stark’s films — an attention to framing that seems to convey a subject’s emotional state almost by accident. Stark confirmed that she’d taken it.

“It’s my brother,” she said, “when he was nine.”

The boy in the photo looked less serious than Stark, a little nerdy and put upon, but the resemblance was striking. Stark wouldn’t talk much about her brother — asked if the two were close, she narrowed her eyes at me as though it was a strange question. She was willing, however, to talk about how photography led her to film.

“I used to feel kind of isolated a lot of the time,” she said, “like I was in a box and the rest of the world was outside the box. After I started taking pictures, I felt less like that. But I started getting really interested in how people move, and you can’t really show that in still photos — or you can, but it’s difficult, and you can only get little pieces of it. So I decided I wanted to make movies, and I made Daniel .”

Daniel is a fascinating, if flawed, first film, but noncompletists probably became aware of Stark after Marianne , the hyper-low-budget feature debut that won Stark the Cleveland Fellowship and the admiration of a number of critics. Even Stark gets animated, in her way, when she talks about it.

“I wasn’t sure I could do it,” she told me between chicken bites. “ Daniel was a documentary, kind of, and I wasn’t sure I could write a whole movie and film it and have it be anything like life.”

Really, Marianne is almost more like life than life itself. Over the course of her career, Stark has been perfecting a particular wide shot, with the camera placed slightly above the actors and giving a nearly 180-degree panorama. It’s not a viewpoint any human being could actually achieve — Stark seems less interested in reproducing life than in transcending it, showing us what it would look like if we were able to step back beyond the bounds of what’s humanly possible.

When I floated this theory to her, she seemed unimpressed.

“Mostly I just try to make what I see,” she said.

Stark’s eyes are huge, and she never seems to blink; it’s possible that she’s able to see a wider angle than most people can.

Marianne was also notable for introducing the unconventional but strikingly talented Allison Mieskowski, who will not be appearing in Woods . Rumor has it that the two were lovers and broke up during the production of Marianne ; Mieskowski did not attend the premiere. Stark would not comment directly on these rumors:

“Jacob wants me to get a publicist so they can tell me what to say to questions like that. But I’d probably still forget and mess up, and then they’d get mad at me. I guess what I want people to know about Allison is sometimes you see someone and it’s like, ‘There, that’s the face, that’s what I’ve been looking for all this time.’ And then everything they do becomes interesting. It’s not always the face though — it could be the way they move, or the way they stand, or even just one of their ankles. It’s like someone walking over your grave when you meet that person, and after that it’s the best feeling, like fitting puzzle pieces together.”

I asked if she was talking about movies or love.

“It’s hard for me to talk about love,” she said. “I think movies are the way I do that.”

Читать дальше