“Your father didn’t die in a snowmobile accident.”

“Then why did you say it?”

“Your father was … the most amazing man I ever met.”

“Then why did you say he was dead?”

“Because — I was so hurt. And I’m sorry. I should have told you the truth.”

“But why? Why were you so hurt?”

“He was … older.” The declaration was meaningless, but Trinnie knew not where to begin. “I thought I’d found — I had found the person I wanted to be with. To spend my life with. And after a little while — a week or two — I moved in. He had a place in West Hollywood, on Alfred. We were so happy . Papa met him — Bluey too … I never introduced my boyfriends to them.”

He turned to his grandfather. “Did you like him?”

“Marcus was a good man,” he said without taking his eyes from Mr. Gehry’s metal gefilte fish. “But I wasn’t glad about what he did to your mother.”

“What did he do?”

The more conversational things became, the more Tull’s anxiety mounted.

“He asked me to marry him. I thought it was a mistake — we’d been having such a good time! See, I wasn’t the marrying kind. I was already twenty-eight and had plenty of offers. I guess I was … superstitious. He wanted to elope, but I said, No, if we’re going to get married, we’re going to get married . Let’s have a big wedding, I said — like a fool. We did. It took ten months to plan. Papa built us a house.” She looked wistfully at her father. “A beautiful house. A strange and beautiful house.”

“The boy should see it.”

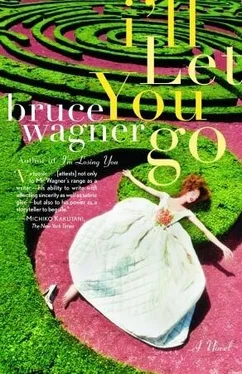

“It was a copy of a real place — an eighteenth-century garden outside Paris, where your father and I had once been. Though ‘copy’ doesn’t sound quite right, does it, Papa?” The old man smiled humbly. “Your dad and I came upon it during our meanderings and fell absolutely in love with the place — and Grandpa built a … re-creation , right in the middle of Bel-Air. The most beautiful wedding present anyone could ever—” Again, she looked toward her father, eyes swollen with tears. Her pain was lancing, and the old man steadied himself against the vitrine that held a knockoff of Le Corbusier’s chapel at Notre-Dame-du-Haut. “But Grandpa kept it a secret. He had artisans from all over the world working around the clock. I used to complain, didn’t I, Papa? ‘What is going on down there on Carcassone?’ That’s what I used to say. The whole neighborhood was in an uproar, but Grandpa kept smoothing things over. God knows who and how much he had to pay to keep everyone happy!”

“I never spent a dime on that sort of thing,” he said, letting loose a gentle chuff or two.

“I’ll bet you didn’t,” said Trinnie sardonically, the smile returning to her face, along with some color. “Six hundred people came to the wedding … I bought my wedding gown last minute, do you remember, Papa? At Christie’s—”

“Oh yes.”

“—Cristóbal Balenciaga himself had cut the material. Everyone arrived in horse-drawn landaus. La Colonne Détruite —that’s ‘the broken column’—it was so beautiful, there was no reason to leave for a honeymoon.”

“They threw rice,” said the old man, prompting.

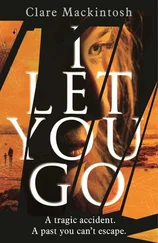

“We stood on the steps and threw rice on the guests as they left.” She gathered herself, nervously smoothing the lap of her gown. “That night, you were conceived. I fell asleep in your father’s arms.” Now her face darkened as the life went out of it. “When I woke up, he was gone.”

“Where — where was he?” asked Tull, trembling.

“It was so quiet! I’ll never forget that. It was the first time — the only time! — we slept there overnight. So you have that funny sleepover feeling — vulnerable. You don’t really … you know that disoriented feeling where your body — where you don’t really know where you are? And nothing’s familiar? The grounds were so huge, so you really did feel like a trespasser in a park … We didn’t have staff, because no one had even been hired. I listened for sounds of him — nothing. I don’t know what I thought at first. I was still floating from the night before! I thought he was in the bathroom or the kitchen. I waited awhile, then went out to find him. I was certain he’d be walking around, but he wasn’t … maybe he’d gone to Nate ’n’ Al’s for deli, to surprise us — breakfast in bed — he used to love that — but the cars were all there. I went back to our room to wait. His wallet and pants were in the upstairs bath, and a book too, thrown facedown on the floor like he’d been snatched off the toilet! I laughed — oh, I thought he was just being evil, evil. Hours and hours and hours went by. I started to feel trapped, like I was losing my mind … I was afraid to call anyone. Then I got angry and then I got scared and then I got mad —at myself— for being mad — and then I got angry and scared all over again and finally called your grandfather.”

The old man wandered closer now. “I had a feeling.”

“You loved him!”

“Yes, Katrina, I loved him. But I had a feeling when you called.”

“What kind of feeling?” asked the boy.

His grandfather’s chest expanded as he took in a long breath. “I knew we would never see this man again.”

Tull nearly swooned with the drama of it.

“Grandpa called an old friend of the family, a detective. I was — I was worried , of course I was worried, that something terrible had happened to him — but in the back of my head — this thing , this jilting thing — I was ashamed to even think it possible this man who I loved and just married had actually disappeared —”

“What did the detective do?”

“Looked for your father,” she said.

Before Tull could ask, his grandfather said: “The gentleman was unable to find him.”

The old man sighed, settling into the Louis XVI.

“But where did he go?” Tull could do nothing about the pleading whine in his voice; he was at their mercy.

“That, my dear grandson, we were not able to ascertain.”

He turned to his mother. “Did — did my father give me my name?”

She smiled. “When we came back from France, he began calling himself Toulouse — demanded everyone at work do the same. He was quite serious about it. Said he was going to get a tattoo: NÉ TOULOUSE. Do you know what né means? ‘Born.’ That was your father’s little joke: Born Toulouse . But you were named after Grandpa too—‘Louis’ is in ‘Toulouse’—”

He wished he were someplace else; remembering his ghostly peregrinations on Carcassone Way, he felt the chill of the profane; he wished Cousin Lucy dead. Yet he no longer felt a fist in his chest, though the weight of the world seemed upon him. His jaw ached from being stuck out, and he dug his fingers into the points beneath each ear for relief.

“Do you know why we were in France?” his mother asked rhetorically. “We were there to visit a film set. One of your father’s clients was a famous actor. We were in a beautiful train station there.”

“The Gare de Lyon,” offered the old man.

“They were shooting a scene where two people say good-bye. We hid behind the camera, watching. It was drizzling— très Parisienne . The actress stood on the platform while her ‘boyfriend’ boarded the train. The cars were already moving. You know: a real movie good-bye. She put her hand on her heart and ran along the track as he waved. He was standing in the door, on a step. No one smiled — the director didn’t want them to. She stopped running and the train kept going. They held the shot until the car was out of sight. The director called, ‘Cut!’ and everyone waited until the train came back to the station to its original mark. After a while, someone yelled, ‘Last looks’—that’s what they say when they’re about to shoot again. ‘Last looks! Final touches!’ The last chance for wardrobe and hair and makeup. Then the scene began again and the actress ran after the train and he waved and no one smiled and then she stopped just where she did before, and put her hand over her heart. Again, the train came back to its original position. ‘Last looks!’ More waving and chasing and chasing and waving, again and again and again. Finally, it was over and your father looked at me and smiled and squeezed my hand. I didn’t remember that until years later.”

Читать дальше