He loped over while Topsy stood on the patch of earth where his house had been. He closed his eyes and imagined the crosshatched honeycomb on the boxes — bugs and marigolds, hawthorn and snakes-head, hummingbirds, cabbage and eglantine that took weeks to evoke. He sighed; his enormous chest heaved skyward. He would not go to Misery House tonight. There was another place he knew, with rooms towering high above the city. As he set out, Half Dead barked halfheartedly while his master ranted against Sanitation and all Departments thereof.

Dusk: a zealous menagerie of untouchables traversed the bridge in a parody of corporate commuting. Where were they bound? Some gesticulated, some nearly loitered, most just rushed along. At least they might take the same direction — but this was a dystopian crusade, all fervor and no cause. At night they built fires at the curbs; by day, they were ticketed for jaywalking by latex-gloved police.

It was close to suppertime and he waded past Misery House and the Midnight Mission with their long lines of the wretched of the earth. A daffy civic-center sign — TOY DISTRICT — loomed on a sidewalk pole, the city’s lame, futile proclamation of a “famous” area. A few of the disenfranchised called hello from their boxes, for the man in tweed was well regarded on the street, and respected for his prodigious physical strength.

Someone-Help-Me gave a shout. Hassled by cops, he had abandoned his stint at the Hard Rock Cafe. He needed a new sign; Will’m made the last, a real crowd pleaser. The vagrant wanted it spruced and was not pleased his greeting went unreturned.

The hulking figure rounded the corner of St. Vibiana without glancing at the notice on the wall: CATHEDRAL CLOSED.

Darkness fell as he reached his destination, a beleaguered ten-story sandstone-finished façade, vacant for decades — brass knobs and piping long since purloined, with shardy windowpanes whose twisted blinds looked as if they’d gone mad before dying; a smell that knocked at the solar plexus, then gusted low over a hellish carpet of syringes, diapers and tampons, soiled to a man, gracing the once illustrious entrance of the Higgins Building, put up in 1910 by the eponymous Thomas H. — who’d made his fortune in copper, as, we may remind, had the father of the original William Morris. Our Will’m arched his neck to read the spray-painted legend

Isa 23—Howl, ye ships of Tarshish; for it is laid waste,

so that there is no house, no entering in

then closed his eyes and imagined: saw women in high collars pass to and fro and bowler’d men from trolleys they called Red Cars: then buggies, bustle and Arrows (Arrows he had gathered from library visits). The main entry, reluctant to admit squatters who blackened marble and checkerboard mosaics with casual fires and human waste, had been welded shut, but Will’m knew another way — the alley.

Only a cat could slip through the twisted iron; so he twisted it more with brute hands, and took a minute to shimmy his large body through. Like a circus strongman, he closed the metal back behind him and went in, letting eyes adjust to the dark.

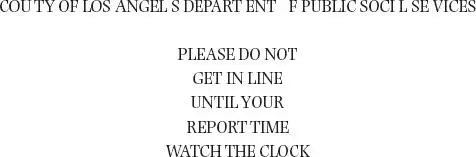

He made his way to the lobby, where the remnants of an announcement from a previous incarnation was glued to a long faux-wood slat:

Debris, shit and more shards. Tumbleweeds of newspaper flecked with concrete dust amid tangle of fluorescent tubes in cool dead brittle bunches. A gang of sullen, sleepy pigeons as he took the stairs, their panicked population increasing on the upper floors, where he headed. Perhaps they were the ones he’d find strutting on lintels in bowlers and high collars — then he’d know once and for all he was truly mad.

What did this place remind him of? Rather, to what place did he let himself drift back? The ruins of the gabled “old stone Elizabethan house” he called Kelmscott Manor … that place was near a bridge, too — Radcot Bridge, on the baby Thames. He thought of the estate as he climbed the littered steps, conjuring drawing room and attic, with rugs and upholstered furniture of his design: motifs of rose and thistle, corncockle and windrush, lily and pomegranate. His blood boiled recalling his dear friend Rossetti’s carryings-on with Janey … dear friend! Beautiful wife! That rankled him and, losing his footing on a droppings-slick landing, he stepped into a crowd of hot, feathered bodies and roared, sloppily killing two with a swat as they rose to escape.

He found a room on the ninth floor he had once used when the night was inclement. Will’m stood by the window a moment, peering at St. Vibiana’s battered cupola; wearily, he lowered himself onto scarred tiles. He heard voices of faceless old cohorts on the telephones and for a moment was not himself. I might yet work myself back , he thought — but what did “back” mean? From what? His duties as Chairman of the Disembodied? And to what? He puzzled, then something stirred behind a closet of besmirched and frosted glass — he would have to rout the animal out before sleep. He stood, opening the warped door to let it scamper: there crouched a wild-eyed girl. She saw his face and dissolved.

“Topsy!” She smiled, then began to laugh. “I was so scared —”

He reached out, and she tumbled to his arms. Her laughter turned to sobs. He held the orphan to his tweedy breast as she cried and cried, and (to his surprise) he along with her.

After a storm of tears, they laughed and wept until laughter won out, and were forever bound.

Amaryllis told him how her mother had been a dead person all this time and how she had been afraid to tell anyone, even Topsy himself, who had been so kind and with whose food she had nourished the babies. How she was going to tell him but was sidelined by a strange troupe of children who were making a movie — a know-it-all girl, a crippled tall-headed boy with mask and gloves, and a wisecracking flaxen-haired star — the orphan waved All About You! before him to prove the celebrity’s pampered, extolled existence. (Amaryllis wasn’t sure why, but she withheld mentioning the boy who on first introduction called himself Toulouse, and Tull ever after.) Then she told him how the police took the precious ones and the Korean gave her away and she’d only managed to escape by dint of what she now felt to be a miracle — or hoped would eventually be recognized as such. And how, because St. Vibiana’s was impregnable, she had come to this place for sanctuary instead …

Topsy listened, moved to sweet astonishment, running oversize fingers through friendly tangle of beard. He had in his vest pocket, visible through a foggy Ziploc’d window, some crushed notes of almond and pomegranate seed, residue of croissant plucked from a dessert song. He spread the sack open and the starved thing dipped in two nail-bitten fingers.

Suddenly, her voice broke. Where did they take the babies? she asked plaintively. They’d be so frightened without her! She sobbed again and couldn’t catch her breath.

“There, there,” said Topsy, patting her shoulder. “They’ll be fine — just fine. And right along, and right along.”

He made her tug from a tap-water canteen, then watched as she cried herself to sleep.

Hours later, Topsy started to a ruckus: someone coughed, stumbled and cursed in the adjacent hall. A shout and filthy flurry of sleep-drunk birds roused the girl, who shrieked as he stood like a colossus to repel the invader. Whoever it was had candlepower, and that meant official trouble. As the beam pierced their room, Topsy snatched the flashlight, punched the interloper’s stomach (which gave the giant no pleasure), hoisted Amaryllis up and fled. The night was moonless; once recovered, the guard would be slow to leave.

Читать дальше