Missus Dotsy took the bicycle on the drive and went off down the road.

Forty-five minutes later she was back. Joe was gone wild with distress again, pacing two steps back and two steps forth in the small space of the parlour. Missus Dotsy snatched the bottle of dew off him and hid it for the time being inside the dresser. The two children were frightened. Jean was under the table in the kitchen, crying. Patrick, normally so fearless, sat at the table shaking his head and saying, ‘Mammy, I’m sorry I ever met that mad cowboy on the bog.’

Not long after, Mister Dotsy’s car rolled into the drive. With him were the two officers of the Local Security Force. Their arrival seemed to pacify Joe.

‘Okay, Joe, okay,’ said Mister Dotsy, easing coyly towards the young airman, all the time holding his gaze as the officers formed a pincer guard on either side. ‘Why have you returned?’

‘I’m just stopping by, sir. I was at the moor again.’

‘But you’ve come all the way from the Curragh?’

Joe took a step back and said, ‘Mister Dotsy — can we have a drink, all of us?’

Missus Dotsy jumped in: ‘There’s some stout left under the stairs.’

In this moment Mister Dotsy put his hand on Joe’s shoulder.

‘What’s the bother, boy?’

Joe sank back into a chair and said, ‘Goddamn.’

He put his arms on the table and flexed his fingers from purple through to white in front of him. He looked downwards and far away.

The three men pulled out the remaining kitchen chairs. Missus Dotsy opened five bottles of stout.

‘How did you escape?’ said Mister Dotsy.

‘There was no escape. I could come and go as I pleased. They gave me a cottage on the camp. All of the prisoners had cottages. I shared mine with three homosexual English sailors who’d jumped from the deck of the HMS Pluck . We had a little picket fence around our cottage, and behind the fence, a little privet hedge. There was a little squeaky gate right in the middle of the hedge and fence. There was a rose bush in the garden — there were two rose bushes. We used to go into the town whenever we wanted. Goddamn.’

‘That’s the second time you’ve said that,’ said the diminutive officer. ‘Mister Dotsy won’t have it.’

‘It’s all right, Marky,’ said Mister Dotsy. To Missus Dotsy he said: ‘Will you build up the fire inside, Mammy?’

‘Nobody sees it,’ said Joe with a snap. ‘There’s no urgency. It’s all rose gardens, all privet hedges.’

‘Now, now,’ said Mister Dotsy. ‘The Curragh Camp is based on the English Quaker model, don’t let it fool you. The ordinary Irishman is hardened by toiling with stones and is ready, believe you me, for Herr Hitler when he lands his jackboot.’

‘Or the English, if they come again,’ said Marky. ‘We’ll be waiting down on Bannow Strand, begad.’

‘God, no, damn, nobody gets it, Jeece! Hitler will blow himself out within a year. He’s not the enemy we gotta worry ourselves with right now. There’s a worse enemy waiting in the wings.’

‘The communists,’ said Marky, emphatically.

‘No!’ said Joe. ‘Not the communists! The communists aren’t even in Poland yet!’

‘That’s not what Father Hannigan says,’ said Marky. ‘He says the communists are everywhere.’

‘ This enemy’s everywhere! They’re here — now — in Ireland. Maybe even just out there,’ said Joe, pointing to the back door.

He turned to look at the door, and sat silently in this way for a few seconds.

He said, ‘Can we take this into the other room?’

‘Now, you’ll just sit here and answer our questions! You’re under interrogation!’ said Marky.

‘You’re not under interrogation,’ said Mister Dotsy, already rising from his chair.

‘Anything you’d like to ask him, Rory?’ said Marky to the taller but still-short officer.

‘Nothing,’ said Rory.

‘Come on inside,’ said Mister Dotsy.

By the fire, Joe told a strange story:

‘Since our unit came to Northern Ireland we’ve been running into trouble with our machinery. Have I told you, Mister Dotsy, that we have some very experimental engineers working alongside us? Engineers and pilots, and technicians from the Lockheed company, all side by side. But there’s another bunch of something in there too. I don’t know what to call it — or them. A couple of spark plugs went missing, that’s the first thing we noticed. This we could handle, to begin with. But then a lot of spark plugs started to go missing, and we stopped cursing about it, and the less we cursed about it and the more spark plugs that went missing, the more ominous it seemed. The even stranger and more ominous-seeming fact about all of this is that the spark plugs were also being replaced faster than our engineers could replace them. In tandem with this activity, certain parts of electrical circuitry would go missing. Often this would not be discovered until our planes were in the air. Then they would immediately return to base, and before the engineers could create replacements these parts were replaced too. Then parts related to top-secret projects started to go missing and be replaced. Stuff to do with radio-controlled flights. Every new item that went missing and went on being replaced brought a greater intensity of ominous silence around the base. The more that was carried on out of sight the less would be discussed within range. Within us all an unfathomable feeling of unease took hold. Among us all a clear idea of the new threat was communicated. I am a test pilot on the radio-control programme. We are to pilot old bombers fitted with explosives to a safe altitude and then parachute out, after which the planes will be remotely piloted to target. That plane in that moor is one of our test planes. We have her stripped of non-essential equipment and fitted with a fake payload. The radio equipment lies mainly under the cowling. While in the air the week before last I noticed the cowling lift. In flight, gentlemen, there is a phenomenon whereby fast-moving air appears to take on a black edge. You see this black air when it hits the solid mass of your airplane, running over its surfaces. But where the black air should have flowed smoothly into and over the raised panel of cowling, it rose well before this, up and around an invisible human-like form. I could make this human-like form out, you see, by the black air flowing around it. I could see it pulling the cowling further away. I had no option then but to quickly down the plane. Once it was on the moor, my priority was to hide the plane as best I could. Evidently your son and I, Mister Dotsy, failed to hide it well: this afternoon I discovered that the mud over the plane was undisturbed but that the plane itself was completely hollowed out of all its internal equipment.’

The officers and Mister Dotsy, who was fascinated by stories about technology, listened to Joe’s story intently. Silence remained for a few moments after Joe had finished.

Then Rory, the taller officer, said, ‘For many centuries the sheeha or deenie ooshla were known in this district for the fixing of wheels. They have a control over the working of things. The fixing of wheels was a way in which they would do you a favour, but sometimes they would spoil things for mischief. They have an understanding of materials but they never use it for real harm. They are pitiable beings. They are like prisoners of our world. They are pitiable for their needs and often they find their needs in us. They have adapted to the world of men and changed with it through all of its ages. If what you say is true then what we could be seeing is a new phase.’

‘A new phase,’ said Joe quietly. ‘Well, I sensed that.’

After they had finished their stout Joe was given his still-filthy clothes from the laundry sack and brought away by Marky and Rory. He did not return again to the Dotsys’ house, but his name was heard once more, years later, after the war, when news came back that some time during the war, probably after the Dotsys had encountered him, he had been killed when the aeroplane he was piloting exploded over the Blyth estuary, GB.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

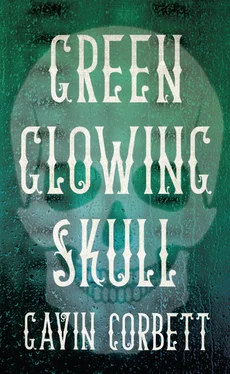

Купить книгу