Frequently asked questions about Living with Bookworms

Q. My community has been infested with strange words! What do I do if I see one?

A. Pray to the Mothers! Send them the page number and locale. Then stop reading in that direction and read the other away as fast as you can.

Q. Is metaphoring contagious?

A. Not that we know of, no. Metaphoring is not an illness or virus; rather, it’s the bookworms’ way of making themselves seen and known. Human beings show no tendency toward metaphoring.

Q. What have we done to deserve this invasion?

A. Nothing. The bookworms have chosen your story at random, in the same way that termites infest a house or typewriters attack smaller typewriters. It’s a question of narrative survival — nothing more.

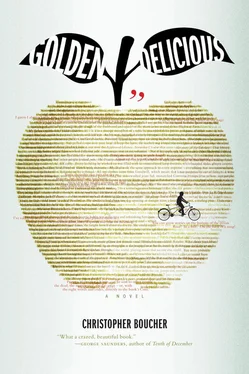

Q. Do the bookworms have anything to do with the disappearance of apples (the blight)?

A. The current theory says yes, that the apple trees — which draw nutrients from the page — were not able to sustain the growth of appletree groves because of bookworm-inspired page-rot. This is one of the reasons that we’re aiming to stop, or at least curb, bookworm infestations. And with your help, we will!

Thanks for doing your part to help save Appleseed from bookworms!

I heard the Fart in the driveway and I put down the brochure. A minute later, my Mom walked in with her reading goggles over one shoulder and her nunchucks over the other.

“How’d it go?” I said.

“O K ,” she huffed, but I knew it went great; her face was as happy as I’d ever seen it. And just two days later, I came home after school and saw two duffel bags by the door.

“  ?” my Mom hollered.

?” my Mom hollered.

“Yeah,” I said, staring at the bags.

“We’re in here,” she said.

I walked into the kitchen and saw my father, mother, and sister sitting at the table. “Sit down,  ,” my Mom said.

,” my Mom said.

I sat in one chair and the Reader sat in the other. “No,” said my Mom to the Reader. “This is for family only.”

“Mom,” I said, embarrassed.

“She can go sit in the TV room,” said my Mom. Then my Mom looked at you.

“Go,” she said.

You got up and went into the TV room. The TV stared at you. “What do you think they’re talking about?” the TV asked.

“I don’t know,” you said, even though you did.

The TV made a face. “What’s the luggage for?”

Then you heard crying in the kitchen. That was me — I was the one crying. “This isn’t fair!” you heard me say.

“  ,” said my Dad.

,” said my Dad.

“It’s not , Dad!” I shouted.

Then you heard the slam of someone’s fist on the table, followed by Diane’s voice. “There are bigger problems in the world than what you’re going to have for dinner ,  ! Appleseed needs me more than you do.”

! Appleseed needs me more than you do.”

Then there was more crying, and the sound of running feet and slamming doors.

“Sheesh,” said the TV. “ That didn’t sound good.”

You sat in the TV room for a while, being watched, and watching others being watched, and finally you clicked the remote and walked quietly out into the living room. Diane was smoking a six-foot cigarette and looking out the window. You opened the basement door and went downstairs. I was sitting on the floor in the middle of a paragraph.

You wanted to say something to me, but you didn’t know what. You already understood what would happen next — you’d read the story about Diane flying away to join the Mothers and the missing that followed/would follow.

“You OK?” you asked. When I looked up and you read my face, you knew the answer.

Reeling from a loss of meaning, thunderous debt, and my Mom’s sudden absence, my Dad turned to get-ideas-quick scams: long-shot prospects, wheelsanddeals, outlandish trades. First he tried trapping and selling memories, but no one would buy them. Then The Ear convinced him to invest some socked-away meaning in a new, virtual kind of reading—“People won’t need pages at all!” The Ear promised — but he disappeared two days later with my Dad’s investment. When my uncle heard about The Ear’s scam he came by the house to check on my Dad — he brought my Dad a Kaddish Fruit, and the two of them shared it outside on the back step. I was out there, too, sitting on the lawn with Sentence.

“Found you a job,” said my uncle, biting into the blue fruit.

“Can I have some of that?” I said, meaning the fruit.

“No,” my Dad said. Then he turned to my uncle. “What job?” he asked, spitting out a seed.

Joump just looked at him.

“ Not Muir Drop,” my Dad said.

Muir Drop Forge, where my uncle worked, huffed on the Kellogg River a mile or so from our house. Muir Drop made work — most of the labor in western Massachusetts was forged there, in fact. In those days, work was all the rage in America — people couldn’t get enough of it — and so Muir was always looking for people. It was backbreaking work, though — the labor they made was grimy, tar-like, pulled from deep in the page. My uncle worked twelve-hour shifts, six days a week, repairing equipment. The injury rate was high at Muir Drop; there were accidents all the time. One day Joump came over with a big burn across his arm where he’d been splashed with toil. Plus, his hands were permanently black from labor that wouldn’t wash off.

“I can’t think of any place I’d rather not work,” my Dad said.

“No shit,” Joump said. “But somanabitch, Ralph. Look around. Just you and the kids now. The banks aren’t just going to stop calling.”

“Thanks but no thanks,” my Dad said. “I’ve still got a few tricks up my sleeve.”

“Tricks,” Joump said. “Like what?”

We found out two days later, when my Dad rounded up me and my uncle in the ropetruck and drove south across Page Boulevard and over Old Five. “OK, I give up,” said Joump. “Where we going?”

“To find the Memory of Johnny Appleseed,” said my Dad.

“Ah, Christ, Ralph — is it too late to turn around and take me home?”

“Yes,” said my Dad, and he drove on.

Since the blight began six months earlier, the Memory of Johnny Appleseed had become a pariah. The Memory didn’t help his cause, either, by proclaiming to anyone who’d listen — at Town Hall meetings, outside the Why — that salvation was just a harvest away; that he’d had dreams and visions of trees shaped like hands holding giant apples, the biggest fruits Appleseed had ever seen. “The blight is not Appleseed’s, but ours!” he’d preach to passerbys outside the Hu Ke Lau. “It’s a failure of imagination! A blight in our own minds!” Most people would ignore him. “And I have found the way forward,” he’d shout after them. “The new soil. We must shed our fears. Boldly move into the unknown. Only then will the apples return.”

We found the Memory of Johnny Appleseed further down Five, walking with his thumb out. My Dad pulled the truck over beside him and rolled down the window. “Where’s your treebike?” he shouted.

“It has—” the Memory of Johnny Appleseed paused, blinked, and sniffed, “—been apprehended.” Then he hoisted his satchel higher on his shoulder.

Читать дальше

?” my Mom hollered.

?” my Mom hollered.