The Librarians put their hands on me, turned me around, and led me back into the lobby.

“Roundhouse-kick them!” said violence. “Pull out their esophagi!”

The Librarians stared at me. “Sorry about that,” said the discoer. “Scanner picked something up.”

“Not checking out any books tonight?” said the discoess.

“N — no,” I said.

“We’ve had problems with that thing,” said the discoer, pointing to the scanner.

“What’s your name?” said the discoess.

“Don’t tell them!” said a thought.

“Make something up!” said another.

“Head-butt the big one and sweep the leg of the small one!” said the thought of violence.

I tried to think of a name — any name. I gave them the first one I could come up with: “Chris,” I blurted. “My name is — Chris.”

“Chris what?”

“Chris B-ook,” I said. “Book.”

“Chris Book ? That’s funny,” said the discoer. “Mr. Book? In a Library?”

“Can you hold out your arms, Mr. Book?”

I stretched out my arms and the discoess patted my shirt and my pant legs. In my mind, meanwhile, my thoughts were scrambling to hide. I could feel them ripping up pages from the book and cramming them wherever they could: in the empty channels and caverns in my skull, in my spinal column, behind my eyes, in my ear canals. The pain was terrible. I tasted words on my tongue, saw words in my eyes: there were letters on the male discoer’s face; the discoess had a W for an ear and her arm was a noun.

The discoess frisked me, stepped back, and looked to the discoer. “Nothing,” she said.

The discoer tapped his head.

“Bend down, please,” said the discoess.

“Everyone act natural !” shouted a thought.

I bent down. The discoess unlatched the lock on my skull and opened it at the seam. The hinge on my skull creaked as she lifted the lid.

I felt her eyes on my brain and I prepared for the worst. They would know that I stole. And then what? “They’ll interrogate you,” whispered the thought of violence. “Torture. Torture like only a Librarian can deliver.”

The female Librarian sighed. “I don’t see anything,” she said. “Just a bunch of thoughts sitting on a couch and watching television.”

“No books?” said the discoer.

“No books, no ideas, nothing,” said the discoess. “It’s like a tomb in here!” She stooped so she could see my face. “Is this place for rent?”

The discoer guffawed and slapped his knee.

“Hardy fucking har,” whispered the thought of violence, from wherever he was hiding in my mind. “I’ll kill both of you motherfuckers.”

The discoess closed up my skull. “My apologies, Mr. Book,” she said. “The alarm must have gone off by mistake.”

“No problem,” said my thought of speech.

“No problem,” I said.

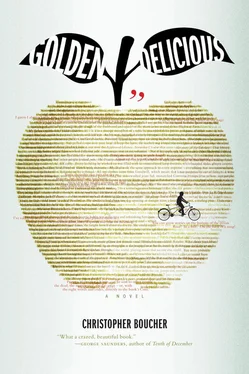

I rushed out of the library and down to the bike racks, where I unlocked the Bicycle Built for Two. I started pedaling away, but I still couldn’t see; the whole world was words and terms. And the noise in my mind — my thoughts, high-fiving and dancing and celebrating — didn’t help either. “Thoughts rule !” shouted a thought of sidewalks. “Fuck yeah!” hooted the thought of violence.

Four blocks from the Library, when I could no longer hear the disco music, I collapsed on the dusky grass. I lay down on my side and my thoughts kicked open my brain and tumbled out of it. “Woo!” shouted the thought of violence, stepping into the grass. “We are badass thought mofos!” he roared. “Aren’t we?”

“That was so cool!” said the thought of walking.

I collapsed in the grass. I couldn’t speak; I was sick with words. The information was blurp reed, yazzing through my > mmm fulcrum.

“  ?” said a thought of home. “You OK?”

?” said a thought of home. “You OK?”

“Are you in need of gutter repair?” I said.

“What?” said the thought of walking.

“The fail is going on all weekend,” I said.

“What fail?” said violence.

“That’s our cornerback guarantee,” I said.

“He’s fucked,” said another thought.

My thoughts colluded to get me standing and walking; I hung over my bike and slowly made my way home. With every step, though, I felt changed; my cells were absorbing the stories — their sentences, symbols, and themes.

Halfway home, we ran into the Memory of Johnny Appleseed praying at the edge of a field of dead trees. “  ,” he said, and stood up. The knees of his pants were wet from the mud. “You OK?”

,” he said, and stood up. The knees of his pants were wet from the mud. “You OK?”

“You’re fine,” said my thoughts.

“I’m fine,” I said.

But I knew Johnny Appleseed wasn’t fooled — he could see the apples in my eyes.

1987 wasn’t an anomaly; the Memory of Johnny Appleseed was wrong. The apples came back smaller the year after that, and smaller still — no bigger than crabs, in fact — the following year. In 1990, no apples grew at all — all the trees in Appleseed were bare. The Board of Select Cones voted to bring in a soil expert from the margins, but all she could do was confirm that the pagesoil was barren — she couldn’t say why or how to solve it. So the Board of Select Cones summonsed the Memory of Johnny Appleseed and demanded a solution. The Memory of Johnny Appleseed held out his hands to them. “I’m really not sure,” he said. “It has something to do with the stories we’re telling. They seem to be sapping the soil.”

The Memory was dismissed, and from then on, vilified. Or is it villainized ? Cast out, outcasted: turned away at his favorite restaurants, denied meaning at his bank, locked out of his own apartment. Soon he was homeless. Rumor was he was sleeping on the streets or in the deadgroves. Sometimes you’d see him outside the Why, handing out brochures.

A host of theories ran through Appleseed: the blight was a curse, prayed upon us out of spite; it was some sort of wildword virus; it was a plot, spearheaded by East Appleseed to destabilize us. Meanwhile, we prayed for a different story, or a better ending to this one.

Overnight, it seemed, Appleseed lost most of its meaning. The applers tried swapping out their central ingredients for another — oranges, lemons, pears — but to no avail. Have you ever had a pear burger? A raw lemon? Ye — uck. Soon, applers began to leave town, hitchhiking over the margins toward richer harvests. The Planters who stayed in Appleseed gave up on perishables and tried their luck with solidifides: they planted chairtrees, for example, or fields of refrigerators.

It wasn’t long before the town’s appleloss hit home. My Mom lost hours at the hospital and had to pick up a shift at Appleseed Mental. That was the thought of small potatoes, though, compared to my Dad’s predicament. First, his tenants started sending in partial-meaning payments, forcing my Dad to hound them — to drive over to the apartments, knock on their doors, and ask them face-to-face where the meaning was. A few times I went with him. Once, we were driving down Belmont Street when we saw a pair of overalls who owed my Dad meaning walking toward the building. We parked the car and followed him inside. The overalls, who used to pick apples at Berson’s Farm before it shut down, answered the door with a four-foot cigarette hanging out of his mouth. When he saw it was my Dad, he nodded and leaned against the doorframe. “Ralph,” he said.

“It’s the ninth, Jaime,” said my Dad.

“Yes, it is,” said the pair of overalls.

“Nine days late,” said my Dad.

Читать дальше

?” said a thought of home. “You OK?”

?” said a thought of home. “You OK?”