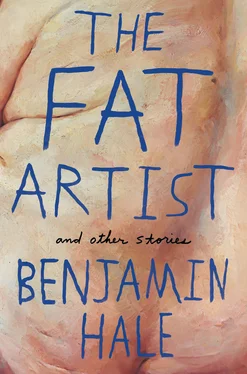

And it wasn’t only the massive weight gain: I had been ignoring all avenues of personal hygiene. Give artist long, tangled beard and long, knotted hair. Give him long, sharp fingernails and long toenails that curl under toes like demonic yellow hooves. Do not wash the artist. Make the artist’s skin sickly pale from long period of entirely interior and nocturnal existence.

Behold the artist.

• • •

First I made a feeble attempt at tidying up my living space, but quickly became discouraged by the overwhelming complexity of the mess. Next I turned my attention to my person. I trimmed and groomed my beard, cut my hair, clipped my nails (both finger- and toe-), showered, brushed my teeth, spat a brown spume of filth and blood into the sink and brushed them again, laundered some clothes and donned them. I was now a much more presentable man, albeit nevertheless a grotesquely obese one. I even liked the rich chocolate-brown beard I had grown. A good, thick beard has a way of dignifying a very fat man.

I reentered society. I reconnected with old friends. It was not hard to get back in the scene. The art world was appropriately appalled, revolted, saddened, intrigued, amused, and delighted with my new body.

My monstrousness made me highly visible. I went back to the parties, back to the VIP openings, returned to the photos in which I stood in the company of the hypermoneyed and/or famous, holding a glass of wine — and damned if I wasn’t bigger than ever.

Through whisper campaign and providence of gossip it became known that I, Tristan Hurt, had spent almost a year in monastic seclusion, working steadfastly on my most ambitious and important project to date: myself. I had spent the last ten months sculpting my body, working as hard on my physique as might an athlete, a bodybuilder, a dancer — but not for the sake of vanity, nor for agility, not to make my body stronger, more robust, or more beautiful. Like my sculptural work before it, my body art was to be deliberately grotesque, and, as Wilde opined all art is, quite useless.

Thus it was that I conceived the installation piece that would revitalize and conclude the career of Tristan Hurt, the Fat Artist.

• • •

I obtained generous financial patronage for the project from the Guggenheim Foundation. I worked closely with Italian “starchitect” Emilio Buzzati to design the structure in which I would be kept. A large glass cube, each side twenty-five feet long, was constructed according to our plans atop the roof of Frank Lloyd Wright’s famous Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum at Eighty-Ninth and Fifth Avenue. My exhibit was constructed on top of the long, flat roof of the rectangular addition to the museum that was constructed in 1992. Each side of my glass cube except the floor was constructed of thin steel girders structurally reinforced with crisscrossing steel cables, forming a grid of twenty-five five-by-five-foot squares, which were inset with plates of glass. The floor was concrete, poured in place, sanded smooth. The room was perfectly transparent all around. Visitors would enter through two wide glass-and-steel double doors in the east wall of the cube. An extravagant bed was constructed in the center of the room, with the back of the headboard flush against the north wall, such that the person sitting on the bed — that is, the Fat Artist himself — could gaze either in a southerly direction across Central Park at Midtown Manhattan, or up through the glass ceiling at the firmament above.

The bed unto itself was a work of art. I designed it. My bed was my last piece of inorganic sculpture. In style, it is deliberately imitative of Louis Quatorze-period furniture, except that those luxurious mid-seventeenth-century beds tend to feature tall posters and canopies with thick curtains, whereas my bed allowed none of these, as I demanded maximum visible exposure of my repulsive body from every angle in the room. In a visually musical series of symmetrical filigrees, the headboard slopes upward into a central peak eight feet from the floor. It is fashioned of mahogany, ostentatiously carved with decorative designs, and gilt with a thin film of gold. The bed is longer and slightly wider than a California king, and its frame was reinforced with sturdy steel rods, in order to support the extraordinary weight that would be pressed upon it. The mattress also had to be custom-made to fit the unusual dimensions of the frame, and also required a three-inch-diameter hole through its upper center. The mattress was designed to be firm and strong, but as comfortable as possible, three feet thick and vacuum-stuffed with a hardy and pliant foam insulation. The bed was covered with a sumptuous sheet of glossy purple velvet, and then piled high with a mountain of matching purple velvet pillows with tasseled fringes of gold thread. The bed was built inside the room on top of an industrial platform scale of the sort used to weigh automobiles and shipping containers. We affixed the scale’s large digital readout to the west wall of my exhibition chamber: accurate down to the fourth digit to the right of the zero, with data presented in both imperial and metric, numbers aglow, red on black. The bed was then weighed by itself and the scale’s zero reset so as to measure only any additional weight. VIIIBehind the bed — obscured from the public’s view of the installation — a hole was cut in the bottom-center panel of glass in the north wall, and we ran a thick rubber tube through the hole, wound it under the bed and up through the hole in the mattress. On the outside of the exhibition chamber, the tube connected to a low-pressure vacuum that would suck waste out of my body and into a septic tank that flushed into the museum’s plumbing system; inside the exhibition chamber, the tube emerged from the hole in the mattress and bifurcated into two smaller tubes, one narrow and one thick: my urinary and rectal catheters. Additionally, an eighty-gallon-capacity water tank was affixed to the north wall, beside my bed. A filtered hose siphoned clean drinking water from the building’s water supply into the tank, and another rubber hose ran from the bottom of the tank and was kept coiled around a hook within my reach on the headboard. A metal ball plugged the lip of the hose when I was not drinking. When I needed to drink water, all I had to do was put the hose to my mouth and push the metal ball in with my tongue to let the water dribble into my mouth. It was essentially a large-scale adaptation of similar drinking apparatuses commonly seen in the cages of hamsters, guinea pigs, and other pet rodents. In this way I would always be kept well hydrated.

• • •

On the roof of the Guggenheim Museum, on a sunny, pale blue day in mid-May of a year sometime in the spirit of the twenty-first century, I, Tristan Hurt, removed my clothes and handed them to an assistant, and with great effort hefted my 493 lb (224 kg) frame onto my bed. I gingerly maneuvered my body as museum staff workers inserted my penis into the narrower of the two rubber tubes, made a seal of adhesive silicone putty, and wrapped the bond in gauze for double reinforcement. Then I slowly turned over and allowed the workers to insert the other rubber tube into my anus, a good two inches deep, and likewise seal the bond with sticky silicone putty. The hole in the mattress was situated directly below where I was to sit, such that I could partially sit up on the bed with no discomfort, my back resting against the plush mound of pillows piled against the headboard.

Although I was naked, I was not indecent, as my genitals were obscured between my enormous thighs and beneath the rolling folds of my lower torso. I spread my legs on the glossy velvet bed and playfully wiggled my distant toes. I reflected on my luxurious comfort. I mentally remarked upon the pleasantly crypto-erotic sensation of the vacuum tubes sucking ticklishly at my penis and anus. I gazed at the faces of the museum workers surrounding my bed. That night the world would get its first glimpse of me at an invitation-only VIP opening exhibition. I was prepared to eat.

Читать дальше