• • •

One night my parents did come unannounced to an opening. They wanted to “surprise” me. Pleasantly, I suppose they assumed. I was, of course, busy, standing naked (rather, nude) in the middle of the gallery floor, masturbating into a raw steak folded in my fist when I saw them walk in. (This was a performance of my piece Pursuance : Artist stands nude in gallery and masturbates into holes cut in slabs of raw meat, which latex-gloved assistants then dunk in tubs of shellac and hang with clothespins, dripping, from suspended wires.) My father’s expression did not change as my mother fled the room. My father calmly walked out of the gallery after her. I was twenty-eight years old at the time.

Later, sometimes I would meet my mother for lunch when she was in the city, but I would not see or speak with my father again.

• • •

There is such a thing as a fame drive. Or call it a glory drive. Like the ability to sing, like a taste for cilantro, it’s something you either have or you don’t. With the exceptions of people who happen to be caught standing in exactly the right place at exactly the right time, or people who happen to be caught standing in exactly the wrong place at exactly the wrong time, almost everyone who ever becomes famous has it, while very few of the people who have it ever become famous, which is why to have it is a curse: It means you will probably feel like a failure for most, if not all, of your life. I have it. I envy and admire those who don’t. Those people can go to bed knowing that they are alive, healthy, and comfortable, and can be perfectly content with that. Those of us who have the glory drive cannot be content with just that. We are not happy unless the number of people we have never met who know our names is increasing. As with money and sex, only too much fame is enough, and there is never too much of it, hence never enough, hence we are never happy. A therapist once told me that people who have this doomed and repellant personality trait have it because of certain kinds of childhoods. What kinds, I asked him. He theorized that it happens to children whose parents tell them they’re wonderful on the one hand and on the other treat them as if they’re never good enough. They pump up your tires, take away your training wheels, and push you down a hill so you can go forth and live a life of restlessly straining to fulfill an inflated self-image, constantly making up for an inward feeling of inferiority. I thought: Mother, encouragement; father, denial — that’s right. That’s me. Feral children are lucky in that they don’t have to worry about this. God, to be raised by dingoes in the wilderness. That’s the best way to do it — this, life: Grow up thinking you’re a wild dog. If these children are out there, I hope for their sakes we never find them.

• • •

The fame, or glory, drive is, at least in men, a relative of, and collaborator and coconspirator with the libido. (Perhaps in some women as well — but I can’t speak to that; I only know that female sexuality is usually more complicated and interesting than that.) I won’t bore you with a locker-room litany of the models and actresses whose interiors I have explored. And I can attest that like the goose that laid the golden eggs, it’s just ordinary goose inside. The pleasure of fucking a model isn’t fucking the model, it’s showing up at the party with the model. That’s a pleasure in its own right, of course, but the real pleasure of sex while famous is fucking people who are less famous than you.

• • •

Olivia Frankel taught creative writing at Octavia College, and wrote quirky, bittersweet short stories about the doomed love affairs of artists. Or so I surmised; I never actually read them. She twitched and babbled in her sleep, talked too much in conversation, and ground her jaw when she wasn’t speaking. She had a thin, squeaky voice that sounded to me like an articulate piccolo. She was pale, and skinny as a bug, and always sat with her shoulders slightly hunched. We were not in love — not exactly — and the relationship did not last very long. We casually dated for maybe about five months. She was initially attracted by my accomplishment, my fame, my easy charisma, my intelligent conversation and sparkling wit, but eventually grew into the realization that I am, in certain respects, a fraud. They always do wind up scratching the gold leaf off the ossified dog turd, don’t they? — the smart ones, anyway, and the dumb ones will eventually bore me.

As a person, I was nearly as lazy as I was self-absorbed. VI had never actually read very much. Almost nothing, really. All that critical theory in college and graduate school? All that heady French gobbledygook? Not counting the front and back covers, I probably read maybe a cumulative fifteen pages of it. That may in fact be an overgenerous estimate. I was, however, blessèd with the gift of bullshit — a blessing that took me far indeed. I knew the names of the writers I was supposed to have read, and could pronounce them with a haughty accuracy and ironclad confidence that withered on the spot those who had actually read them. Believe me, I could slather it on so thick and byzantine that most people — even those who did “know” what they were talking about — were dazzled to silence by the fireworks of obfuscation that burst from my mouth when I spoke. VI

Olivia, however, learned to see through it, and was probably a bit irritated with herself for having been at first seduced by it. A few friendly interrogations over dinner on matters approaching the erudite were enough to reveal that I probably had not finished a book since high school. So, in the first few months of our nearly meaningless affair, back when Olivia was still at least ostensibly entertaining the possibility of allowing herself to love me, she bought me a present: a volume of the collected stories of Franz Kafka. Written on the inside front cover, in her filigreed female handwriting (but in rather assertive black marker), was the businesslike inscription: “Tristan— Here you go. Most of them are pretty short. Olivia.”

That sign-off was characteristic of her, by the way. No “love,” no “with love,” not even a tepid “best wishes.” Just her first name followed by a period, as if that alone constituted its own sentence. VII

For her I was probably at most a brief, interesting infatuation or experiment. I don’t think she was ever really in love with me. She did once tell me I was the most, quote, “fake and pathetic person [she] ever made the mistake of fucking.” Much later, she also told me she would, quote, “call the cops on [me] if [I were to] show up [at her apartment] coked out of [my] mind [in the middle of the night] again.”

• • •

But all that is beside the point. I mention Olivia only by way of explaining how it was I came to admire Kafka’s haunting allegory, “A Hunger Artist.” A man sits in a cage and refuses to eat. He is gradually forgotten by the public. He starves himself for so long that everyone ceases to care. But his art goes on — unto his death. His last words are: “I couldn’t find the food I liked. If I had found it, believe me, I would have stuffed myself like you or anyone else.” When he dies, they sweep out his cage and replace him with a young panther. “The food he liked,” writes Kafka, “was brought him without hesitation by the attendants; he seemed not even to miss his freedom.” The people crowd around the cage that now contains this creature so ardently alive, and “they did not want ever to move away.”

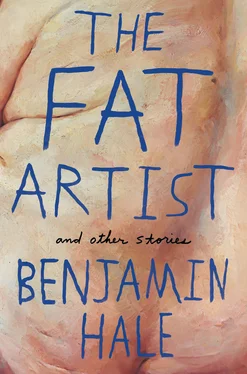

Starvation — my goodness, is that a dark metaphor, Mr. Kafka. Take a look at the cover of the book: Kafka peers out at you in grainy black and white, his dark hair slicked back from his temples, his eyes wide, wet, hunted-looking. His cheekbones are high and brutally sharp, his cheeks sunken. He looks malnourished already. We know his sisters died in Auschwitz, which is doubtless where this man’s skull would have wound up, scrabbled in a ditch along with thousands of other Jewish skulls, had tuberculosis not mercifully knocked him off at the age of forty in 1924. He died of consumption, as the Victorian euphemism goes — because the disease consumes one from the inside out — whereas I, Tristan Hurt, would set out to die of a different kind of consumption. What if — I wonder — Kafka had not coughed himself to death, but had lived long enough to be herded onto a cattle car bound for Poland, where the writer/insurance underwriter (who, like me, bitterly resented his father) would have been stripped, shaved, tattooed with a number, starved, and forced to dig his own grave? It would not have taken this wan, skinny little man very much time at all to begin to look like the men lying on the bunks and wincing at the daylight as the doors of Auschwitz, Buchenwald, and Dachau rolled open in the spring of 1945: horrifically thin, eyes sunken, ribs like claws. He was halfway there already. This man himself resembled the hunger artist. But in those penetrating but deeply sad eyes, evident even through the poor exposure and the fuzzy focus, there is a hunger beyond the merely physical — this man was starving not only because he felt caged in by his oppressive family and besieged by the zeitgeist of his interwar Prague, but was suffering a starvation of the soul, an insatiate hunger of the spirit.

Читать дальше