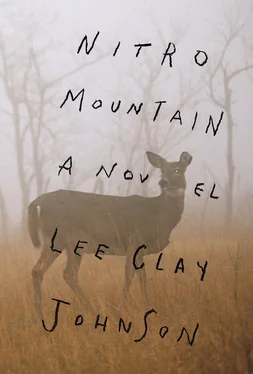

When my turn came, they set another date and Wesley got the out-of-state restriction dropped. “I’m free to go?” I said.

“For now.”

“I can still drive and shit?”

“Innocent till proven,” he said, bringing out a handkerchief and pulling at his nose with it.

“Probably lose my license, right?”

“We’re still waiting on the blood tests.”

I felt like an idiot for not knowing this was all that was going to happen. The spot on the street was still mine for another hour, but I didn’t know what to do with myself and drove back home and slept the rest of the day.

—

The shelter finally called and I went in. A sex felon with eyes that moved quickly and independently of each other told me I’d made Crime Times . He kept up with the paper, looking for friends and family members he hadn’t heard from in a while. “What the hell you been doing, huh?” he said. “You supposed to be an example for us shitheads, ya shithead.”

“I know it,” I said. “But listen, the charge is bogus. I didn’t do anything. They pulled me over for false reasons.”

He shook his head. “That mugshot of you,” he said. “You look rough, bubby.” Most of his teeth had been knocked out in prison, and here he was calling me rough. “If they do end up booking you,” he said, “I’ll write my cousin, make sure he don’t give you no hard time.”

“I appreciate that.”

“And you ain’t gotta worry — I won’t tell nobody else.”

“You’re not the only one who reads that trash,” I said.

“Maybe not, but I’m the only one that understands it.”

After my shift I went looking for the paper. It wasn’t a proud moment, walking into Joy Imperial and seeing my face on the front cover in the rack. I dropped it on the counter next to the six-pack I’d pulled from the cooler.

Rachel was working, and I hadn’t looked up at her yet. “That all?” she said. She rang up the beer, put it in a plastic bag and then threw the paper in. “For free,” she said.

“Didn’t have to do that.”

“I kinda do,” she said. “It’s like required. If you make it in, you get a free copy. Want another?”

“No thanks.”

“It’s not a bad picture,” she said. “You look fine.”

She, on the other hand, looked older since I’d last seen her. Maybe she was. She pushed the bag toward me and said, “Look on page three when you get home.”

The beer was Dad’s. He had a mini fridge in his room where he liked it kept. I took two and went to my room, cracked one open and scanned the paper till I found me, then turned to page three, and there was Daffy. From the front you could see only the fading bill on his neck. His name was Arnett Atkins.

Charged with video voyeurism. Felony.

Those nights at my parents’ place, I lay fetal in bed and prayed to God for something good to happen in my life. Afterward I felt bad for even asking; I’d never requested a blessing for anyone else, but here I was, whimpering, Please, more for me, I won’t throw it away this time . What worried me was that I didn’t know if I’d actually be able to not throw it away. All matters lately seemed to slip through my fingers. Because of the prayers, I felt all the more deserving of what was happening to me. I didn’t believe there would ever be an end to it, except maybe for the end.

—

One morning, Mom drove me to the Bordon library so I could check my email. She was going to run a few errands and come back in an hour to pick me up.

The library was clean and warm, like a classroom, and that made me feel out of place. I had a message from Jones in my inbox. He’d sent it almost a week ago, telling me to call him back as soon as I could. He’d been offered an opening slot to tour with Marshall Mac and the Deputies, a popular band around the state. Marshall liked to let his band spread out into long jams while he rapped about his tractor truck — some hillbilly hybrid rig. That was the title of his latest album: Come Take a Ride in My Tractor Truck . I asked the librarian if I could use the phone.

Jones answered on the first ring. “What’s happening?” he said.

“Just got your email.”

“Can you do it? I was worried about you.”

“I’m all right.” I almost jumped in the air. “You ain’t found anybody yet?”

“This tour’s going to be a long one. Most folks have lives.”

“Suckers.”

“Can you make practice every evening this week?”

“Yeah. Wait. I don’t know. Where is it? I don’t got a car yet.”

“We’re over in Ashland, still practicing in the storage unit. There’s a couch to crash on. You can live here till we leave, for all I care. I’ve done it before.”

I knew then that despite how selfish my prayers had seemed, they’d worked. “I don’t want to take your bed.”

“I’ve got the van. And the nests of a couple other birdies. Don’t worry about me. I’ll pick you up tonight. Bring a sleeping bag and a box of diapers.”

I handed the phone back to the lady behind the desk. “I prayed for it,” I told her. She was around my age but had the sorrowful smile of a woman who’d worked one job her whole life. “I prayed for it and I got it,” I said. “I’m going to be opening for Marshall Mac.”

“Never heard of him.”

“That’s okay,” I said, and took her hand. “I can get you on the guest list.”

She pulled away and studied me. “You’re planning to play music with your arm like that?”

“Like what?” I said, and played some air bass at her.

—

Jones drove me over the mountain into Ashland. The van reeked of body odor, cigarettes and spilled beer, like it always had, but now I was part of the band and felt connected to the stink. The passenger bucket seat was sprung and I could feel the wires under me. We didn’t listen to music or talk much, just kept the windows cracked with cigarettes burning.

The storage unit was packed to the air vents with instruments and sound gear. The couch against the sidewall was covered in set lists, notebooks, empty cigarette packs. I picked up a page full of words, and at the bottom there were some verses that hadn’t been scratched out:

If I had my way I’d leave here tomorrow

Hitch up a ride and ride on down to Mexico

But there’s just one thing I gotta do

“Don’t read that,” he said. “I don’t go peeping through your stuff, do I?”

I dropped it onto a pile of duct tape and broken drumsticks.

“It ain’t done yet,” he said.

“What’s it about? What’s the one thing you gotta do?”

“That’s what I’m figuring out. Anyway, it ain’t about me.”

He showed me around the room, where the light switch was and how to open the door with a crowbar from the inside. There was also a space heater that started throwing sparks if you left it on for more than three hours. “And if the cold doesn’t wake you up,” Jones said, “the smoke will.”

After he left, I gathered his papers off the couch and made my bed. I read through his lyrics late into the night. Some of the songs I’d heard him sing before, and I could hear the melody behind the words. Others were new to me, a lot of pieces, verses and hooks. I’d never had the chance to look at anything like this. His songs seemed so simple that I never thought of the time he put into them. I decided I was going to play bass better than I ever had, just for him. This guy was good. He could be my escape.

The next morning I packed my sleeping bag into Jerry’s bass drum and headed over to Hardee’s for some coffee and a biscuit. I used as much free cream and butter and jelly as I could. When an employee came over and told me I had to quit taking the stuff, I tossed a packet of half and half into my mouth, chewed it up, swallowed the cream and spit the plastic into the countertop’s trash hole.

Читать дальше

![Lee Jungmin - Хвала Орку 1-128 [некоммерческий перевод с корейского]](/books/33159/lee-jungmin-hvala-orku-1-thumb.webp)