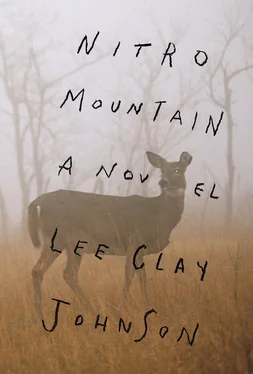

Arnett and I used to make trips down to the Tri Cities. The Hillbilly Bermuda Triangle. We were transporting what he called Robot, a mixture of heroin and meth, and we felt good about the dynamics of the product. We traveled a lot of it in the spring, the hillsides blushing like baby cheeks. In Bristol we stopped at what looked like a garage to load the truck with gutted pinball machines, stuffed to their limit with Robot, then headed over to Johnson City and Kingsport, making the rounds to a few different bars, dropping off the machines and making bank.

We didn’t drink on those trips. Arnett said we had to stay clear. I’d get the shakes so bad, but I pushed through and we made all the deliveries. Arnett knew everybody. I just stood there behind him like a smiling statue. Some of them were the nicest folks you ever met. They gave us beds in their houses. Fed us dinners. Coffee in the morning. Kingsport was the prettiest, with its open river and safe mountains. The downtown was like a cradle. It made me feel like everything was okay. Arnett was suspicious of that feeling, but I loved it. We ate a couple times at Ball Breakers. It sounded like they were always hiring. I marked it as a place to go, if I ever had to run.

I shared the front seat of the bus with a lady who’d just got out of a shelter for broken women. She was a sweet round toy who went by the name of Diana. Bandages over her wrists and no hands. We sat together and watched the night race at us headlong. I didn’t mention her hands, the lack of them, but she brought it up. Said she was washing dishes one night when her husband came behind her and fed each one, fingernails first, into the garbage disposal.

I rested a hand on her shoulder.

She kept talking like she didn’t notice. “My lawyer proved my husband had sharpened the blades or whatever in advance, so it showed premeditation. But I don’t think that’s true. He never meditated. It was passionate.”

I asked why he’d done it and she said, “He saw me touching his car in the driveway. He’d just washed it and polished it. That’s why he done it. He just couldn’t get the idea out of his head of my dirty hands all over his new car. It was a new Ford Focus.”

“Honey,” I said, “nobody’s allowed to cut off anybody’s hands, not over a Focus.”

“Mine you can,” she said. “He worked his whole life for that car.”

The bus let her off at some gas station, where not a single light was on in the parking lot. The driver asked if she had somebody coming to pick her up.

“Eventually,” she said.

—

Ball Breakers hired me like the day I got there, which was lucky. Probably because of Amanda, who I ended up ditching. And now I was a sorry-ass country song, thinking of the used-to-bes, remembering when, etcetera. Working this register. Just the words green grass would get my chin going. I never saw anybody, except for all those dudes playing pool. And their frosted girlfriends. And Don, of course, who smiled at me with pieces of leftovers in his teeth that his wife — yes, of course — packed and sent to work, even though we made our own food here.

I figured Arnett had got convicted. That’s why he hadn’t been writing me letters.

So I was standing there making change, bound to miscalculate something every other time, when Don walked up the stairs from the billiard room swinging his big hairy arms. “Mind mopping up a mess in the ladies’ room,” he said, “if you’re not doing anything? Thanks.” He shot me in the chest with his pointer finger.

I went down and dodged between the tables and through the noise of men drinking beer and betting and laughing. Loud radio rap-country from the ceiling speakers. A guy I didn’t know put a cue in front of me like an arm at a tollbooth and nodded at a guy in jeans bending over to break in front of us. The triangle exploded. One solid and one stripe fell in at the same time in opposite corners. “Choose which you want,” he said to the guy who held me up. “You can have it either way.”

The cue lifted and I dodged through the crowd to the closet. I filled a yellow bucket on wheels with hot water and bleach, stuck the mop in and pushed it across the floor and into the ladies’ room. It wasn’t so bad and could’ve been cleaned up in less than a smoke break, but I wanted to take my time.

Don came in while I was down on one knee and reaching the mop head back beneath the toilets, trying to get it all up.

“That’s good enough,” he said. Now that he was in here, I could feel my panties riding up behind and showing. “I didn’t mean for you to take all night. We’ll deep clean it when we close.”

I pulled the mop toward me and went to stand.

“Stay,” he said. “Good girl.”

I did, out of hatred of him I stayed kneeling on one knee and bent over, holding the mop in my hands. He probably expected me to get up and say something sharp and walk away. But I stayed, letting him look at it, until he told me to move. He was going to feel bad for doing it when I didn’t say anything back.

“Ah, Jennifer,” he said. “I’m just playing with you. Come on, get up, I’m just messing around. Don’t make me feel like I’m making you do things you don’t want to.” In the mirror, he flicked his dick through his jeans.

—

Why hadn’t I just figured it out for myself? I called information and got connected to the Ashland County Regional Jail. A voice gave me a choice of extensions to hit and I finally guessed the right one: 5 for Records. Arnett Atkins? The lady said she’d check, came back on and said, “Left eight days ago.”

“But he told me he was in there for longer,” I said. “Like forever. That’s what he said.”

“I don’t know what he told you,” she said. “But he had a morning discharge on, let’s look here, the fourteenth. Bail.”

“Well, where’d he go? You know what he’s gonna do to me?”

“I can connect you with the magistrate if you’d like to make a file.”

I hung up and kept my hand over the receiver like it might lash back at me. But then I got this strange feeling of excitement. Couldn’t believe I hadn’t thought to call. Something so damn simple. I didn’t think this was how I was going to feel. Now I could tell him about Don. But no, don’t start that stuff.

He was out, that was enough. The one person who’d never judged me. The one person who’d ever forgiven me.

Back home I took a shower and got into bed. Clean skin between clean sheets. I missed my bed smelling like bodies, like sweat, like dirt, like him. My scars had mostly healed, except on my shoulder. You couldn’t really tell what they were anymore. I threw off the sheets and looked down at them. They could’ve been anything. Birthmarks. Poison ivy. Except for that graze in my shoulder, just a shade pinker than my nipples, sewn shut like lips.

I knew he was to blame for my whole situation, and for the longest time I’d hated him. That’s what had sent me going after him like I did. We were always drinking and we didn’t know how to stay away from each other and keep from fighting. I’ll go ahead and admit it: I was a big problem. I loved fighting. But I was past all that now.

I woke up with my face in the pillow. The morning was noisy with birds in the bushes out front. It was this big bush that Don wanted me to trim but I never got around to it. I was already slacking on my duties as a tenant.

What Arnett wrote, that he’d never see me again — I felt okay with that at the time. Maybe in normal society you’re not worried every day. But when there’s nothing wrong, what’s the point?

I left to go to work and birds scattered out of the bush.

I’d given myself time to stop for coffee and was in no rush. The little strip of downtown started with Annie’s Antiques, then Carl’s Café, then Mike’s Music & Pawn. Carl’s wasn’t so bad with the smell of fresh coffee grinding and the shiny wood floors. I took a seat at the counter. Reece was working today. He had hands that always moved toward you. He took a mug hanging from a hook with a dozen others and set it in front of me.

Читать дальше

![Lee Jungmin - Хвала Орку 1-128 [некоммерческий перевод с корейского]](/books/33159/lee-jungmin-hvala-orku-1-thumb.webp)