— There are day tickets, he said.

— I know.

— We can get a few.

— I know.

— Great.

— I was thinkin’, said Jimmy.

— Yeah?

— Maybe we could give Kevin a few more songs.

— No, said young Jimmy.

— One, even.

— Don’t wreck it, Dad.

— You’re right.

— Les?

— Jimmy.

— How are yeh?

— Fine. You?

— Fine, grand, yeah. How’s Maisie?

The usual little pause.

— Fine.

— Great. The Olympics went well.

— Yes.

— Did you get to annythin’?

— No.

— Watched it on telly, yeah?

— Some.

Jesus, what was he doing?

— Come here, he said. — Do yeh like your music?

— What do you mean?

— Do you follow the music, yeh know — go to gigs, ever?

— Not really.

— No?

— No.

— Well, listen.

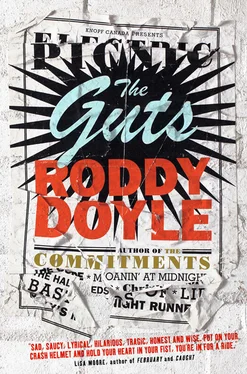

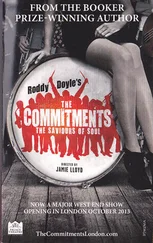

Jimmy told him about the Picnic. The yurt, Outspan, Des. The Cure. Elbow. Dexys Midnight Runners. The free ticket. He could give it the full Jimmy because he knew the answer was going to be No.

— So. Would you be up for it?

— Yes.

— Yes?

— Yes. It sounds great.

— Great, said Jimmy.

He meant it, and that was a shock. It was like something warm flowing down through him — the anaesthetic he’d had when he’d had the bowel whipped out; that same rush.

— Jimmy?

— Yeah.

— Still there?

— Yeah.

The house was calm again.

Marvin had gone down to the school. He’d said he’d text when he got the news, but he hadn’t.

— Send him a text, said Jimmy.

— Why me? said young Jimmy.

— You’re not me or your mother. He’ll answer you.

— Go on, Jim, said Aoife. — Please. The tension’s killing me.

They watched young Jimmy pulling his phone out of his pocket, like he was pulling barbed wire from his hole. They watched him compose the text and send it.

— What did you say? Aoife asked him.

— It’s private.

Marvin didn’t text back.

— Will we phone him? said Jimmy.

— Yes. Maybe.

— He’s only been gone half an hour. How far is the school — to walk?

Young Jimmy had disappeared. So Jimmy went up to Mahalia’s room and woke her.

— How long does it take you to walk to school?

— What?

He asked her again.

— Like, I haven’t walked to school in, like, months. It’s the holidays, like.

— How long though — about?

— I don’t remember.

— A rough guess.

— Ten minutes. Go away.

— Okay. Thanks.

He went back down. He hadn’t noticed Marvin actually doing the Leaving in June. Now but, he was shitting himself. Jimmy hadn’t done the Leaving. He’d left school a few months before the exams.

They felt a shift in the air inside the house before they heard the front door closing. And they were up and out, skidding into the hall to get at Marvin.

— Well?

— Three hundred and forty points, said Marvin.

— Is that good?

— Of course it’s good, said Aoife.

— Brilliant, brilliant. Will it get you what you want?

— Think so, said Marvin.

He wanted to do Arts or something, in UCD.

— If it’s the same as last year, said Marvin.

There was the hugging.

— Proud of you, son, said Jimmy. — Always.

The excuse was great, the fuckin’ window. He could gush and let himself go. Maybe exams weren’t such a bad thing. Marv’s arms were around him too.

— I’m proud of you too, Dad, he said, the sarcastic, wonderful little prick.

Now he could phone the Halfbreds. Barry or Connie?

He went out to the back garden.

Connie.

He didn’t think the phone rang even once.

— Five hundred and sixty points, motherfucker!

— Congratulations, Brenda.

He seemed to remember Connie screaming something about the points her daughter would need to earn the right to shove her hand up donkeys’ cunts.

— Five hundred and sixty!

— Great stuff, said Jimmy. — So she’s all set to become a vet.

— Oh yeah!

Connie was never going to ask him why he’d phoned.

— I’ve some more good news for you, Brenda.

— What?

He’d got them — Noeleen had got them — a Picnic gig, half an hour in one of the tents, to replace Little Whistles, two girls with guitars and flowery dresses. Their auntie had died; she’d been the inspiration for their big song, ‘Forget Whatever’. So they’d cancelled all gigging till the new year.

— I’ve a gig for you, Jimmy told Connie. — The Electric Picnic.

— We’re not going on before the fucking Cure!

He took a quick breath.

— Or Patti Smith! said Connie.

— Christ, said Jimmy. — Will Patti Smith be there?

— Not on my fucking stage.

Jimmy could hear a girl crying happily behind Connie. That would be the kid with the points, the donkey lover.

— I’ll make sure Patti stays away, said Jimmy.

— G.L.O.R.I.A. spells fuck off, bitch!

— Good one, said Jimmy. — So you’re up for it, yeah?

They’d been screaming at him for a decent gig, for months — for years.

— I’ll think about it.

— Grand, said Jimmy.

Aoife needed the car.

— Why?

— I’m going too, she said. — Remember?

— Shite, yeah — sorry. Can yeh not get the bus?

— Jimmy.

— Grand, okay. Shite. Not you — life in general.

Des had sold his car and Jimmy was fairly certain Outspan didn’t have one.

Do u own car?

Xwife says its hrs .

— Da?

— Jimmy.

— Howyeh.

— We’ve Leslie here with us.

It was Wednesday night and Les was staying at the folks’ until they headed down to Stradbally and the Picnic on Friday.

— Great, said Jimmy.

Slap the fatted calf onto the fuckin’ barbecue .

— I’ll be over tomorrow night.

— Wha’ time? his da asked.

— Why?

— We’re goin’ out for a meal, said his da. — Leslie’s treatin’ us.

— Brilliant, said Jimmy. — But come here. Can I’ve a lend of your car for the weekend?

—’Course.

— It’s to get us to the festival. Aoife needs ours.

— No bother, said his da.

— Thanks very much.

— Delighted to be of help.

His da sounded so happy. He told Aoife about it.

— Because Leslie’s come home, she said.

— Yeah.

— And why’s that?

— Because —

It hit him.

— Because I asked him.

She laughed.

— And how does that make you feel?

— Eh — good, he said.

— Where’s tha’ Swiss Army knife?

— You’re not serious.

— I am.

— It’s two in the fucking morning, Jimmy.

— Exactly the time o’ day when you’d need a Swiss Army knife. I didn’t mean to wake you, by the way.

— Why would you need a knife?

— Cuttin’ rope, self-protection, killin’ Outspan.

— Come back to bed.

— Okay.

She pulled him tight to her.

— You’re going to have a great time.

— I know.

Her knee whacked his arse.

— Sound convincing.

— I know .

— That’s a bit better. Stop worrying.

That annoyed him.

— I’m not worried, he said.

He didn’t think he was lying.

— What’s the worst that can happen?

— Listen, he said.

He tried not to push away from her.

— I’m not one of the kids.

— I’m just —

— Stop fuckin’ patronising me.

She said nothing. Her knee was gone. But her arm was still there.

— Listen, she said. — I’ve been doing it a lot. Since your diagnosis. Which wasn’t even a year ago, by the way.

Читать дальше