“I think you gave me a fat lip.”

“I can do better.”

“Another one like that and I won’t need the zoo pass.”

“The fishing pole, then.”

“Maybe it was the satellite,” she says. “All that pressure to perform.”

“They’re watching us on the Weather Channel right now.”

Sue gets a conspiratorial look on her face. “I saw at least three satellites up there. How many did you count?”

You’re both treading water, breathing hard between phrases.

“They were fucking everywhere, ” you tell her.

“That Mrs. Cassini. I think the satellite she’s talking about is halfway to Saturn.”

Sue’s treading water with you, and that’s a good sign. You know you’re going to kiss her again. You have a photo of your mother safe with a friend and a mild case of shock. You’re immersed in ice water, losing blood fast, and still you feel an erection coming on, the kind you’d get when you were sixteen, appearing out of nowhere, surprising you with its awkward insistence on the terrifying prospect of joy ahead.

I

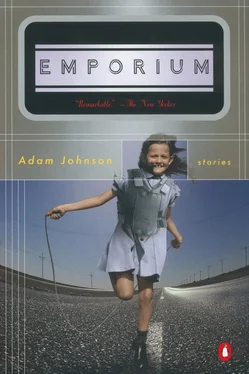

The Body Armor Emporium opened down the street a few months back, and I tell you, it’s killing mom-and-pop bulletproof vest rental shops like ours. We’ve tried all the gimmicks: twofor-one rentals, the VIP card, a night drop. But the end is near, and lately we have taken to bringing the VCR with us to the shop, where we sit around watching old movies.

Lakeview was supposed to expand our way, but receded toward the interstate, and here we are, in an abandoned strip mall, next to the closed-down Double Drive In where Jane and I spent our youth. After Kmart moved out, most of the stores followed, leaving only us, a Godfather’s Pizza, and a store, I swear, that sells nothing but purified water and ice. It is afternoon, near the time when Ruthie gets out of school, and behind the counter, Jane and I face forty acres of empty parking spaces while watching Blue Hawaii .

I am inspecting the vests — again — for wear and tear, a real time killer, and the way Jane sighs when Elvis scoops the orphan kid into the Jeep tells me this movie may make her cry. “When’s he going to dive off that cliff?” I ask.

“That’s Fun in Acapulco ,” Jane says. “We used to have it on Beta.” She sets down her design pad. “God, remember Beta?”

“Jesus, we were kids,” I say, though I feel it, the failed rightness of Betamax smiling at us from the past.

“I loved Betamax,” she says.

I only rented one vest yesterday, and doubtful I’ll rent another today, await its safe return. There aren’t many customers like Mrs. Espers anymore. She’s a widow and only rents vests to attend a support group that meets near the airport. The airpark’s only a medium on threat potential, but I always send her out armed with my best: thirty-six-layer Kevlar, German made, with lace side panels and a removable titanium trauma plate that slides into a Velcro pocket over the heart the size of a love letter. The Kevlar will field a.45 hit, but it’s the trauma plate that will knock down a twelve-gauge slug and leave it sizzling in your pant cuff. I wear a lighter, two-panel model, while Jane goes for the Cadillac — a fourteen-hundred-dollar field vest with over-shoulders and a combat collar. It’s like a daylong bear hug, she says. It feels that safe. She hasn’t worn a bra in three years.

The State Fair is two weeks away, which is usually our busiest season, so Jane’s working on a new designer line we think may turn things around. Everyone’s heard the reports of trouble the State Fair has caused other places: clown killings in Omaha, that Midway shootout in Columbus, 4-H snipers in Fargo.

Her custom work started with the training vest she made for Ruthie, our fourteen-year-old. It was my idea, really, but Jane’s the artist. The frame’s actually a small men’s, with the bottom ring of Kevlar removed, so it’s like a bulletproof bolero, an extra set of ribs really. The whole lower GI tract is exposed, but fashion, comfort, anything to get the kids to wear their vests these days. Last week I had Jane line a backpack with Kevlar, which I think will rent because it not only saves important gear, but protects the upper spine in a quick exit. Next I want to toy with a Kevlar baby carrier, but the problem as I see it will be making a rig that’s stiff enough to support the kid, yet loose enough to move full-speed in. We’ll see.

Through the windows, there’s a Volvo crossing the huge lot, and I can tell by the way it ignores the lane markings that it’s not the kind of person who cares about the dangers of tainted water and stray bullets. The car veers toward Godfather’s Pizza, almost aiming for the potholes, and Jane sniffles as Elvis hulas with the wide-eyed orphan at the beach party. “Remember Ruthie at that age?” I ask.

“You bet,” Jane says.

“Let’s have another baby.”

“Sure,” she answers, but she’s only half listening. She really gets into these movies.

After Elvis is over, Jane makes iced teas while I drag two chairs out into the parking lot so we can enjoy some of the coming evening’s cool. We bring the cordless phone, lean back in the chairs, and point our feet toward sunset. This time of day brings a certain relief because even in September, a good vest is like an oven.

There is a freedom that comes with doom, and lately we use our large lot to play Frisbee in the evening or football in the near-dark, with Ruthie always outrunning one of us for the long bomb. Some nights the Filipinos who own the water store drift out under the awnings to watch us. They wipe their brows with apron ends and seem to wonder what kind of place this America is.

Honestly, I’ve lost most of my spirit in the fight against the Emporium. When we opened, we were cutting edge, we were thinking franchise. Our customers were middle class, people like us; they still wanted to believe but understood that, hey, once in a while you needed a little insurance. Their lives were normal, but nobody went out on New Years without a vest. To buy a vest ten years ago was to admit defeat, to say what’s out there isn’t just knocking at the door — it’s upstairs, using your toothbrush, saying good morning to your wife.

As the sun sinks lower, we watch the first pizza delivery boys of the evening zoom off in their compact cars, and it’s a sight that hurts to see. These are high-school kids, most of them too poor to afford or too young to appreciate the value of a vest. I mean, they’re going out there every night as is, which makes them all the more alluring to Ruth.

People used to make excuses when they came in to rent a vest— vacationing in Mexico, weekend in the city, reception at a Ramada Inn, flying Delta. Now they’re haggling over expired rent-nine-get-one-free coupons. Now they’re going to the Emporium to buy sixteen-layer Taiwanese knockoffs for three hundred bucks. The Emporium is 24-hours, something I’m philosophically against: you should see the tattoos on some of those guys coming out of there at 3:00 A.M. These days people are making the investment. They’re admitting the world’s a dangerous place.

Across the parking lot, we see Ruth pedaling toward us. She’s wearing a one-piece red Speedo, her training vest, and the Kevlar backpack. Her hair is still wet from freshmen swim practice. She meanders over, awkward on a Schwinn she is now too big for, and pedaling big, easy loops around us, announces that she’s an outcast. “Only dorks wear their vests to school,” she says. “You’re killing my scene.”

It feels good though, the open-endedness of the day, the last light on my feet, being the center of my daughter’s universe for a few minutes. Ruth pedals then coasts, pedals then coasts, the buzz of her wheel bearings filling the gaps in our afternoon, and I almost forget about the Emporium.

Читать дальше