“Hamdi-Ali.”

“Hamdi-Ali?”

“Yusef Hamdi-Ali.”

“Listen, ya Yusef. We’re a small people. We’ve always been a small people, because our God demands a lot of his believers, and not everyone is willing or able to meet these demands. Our religion is a difficult one, and not accepted by many. Our neighbors do not like us, and they’ll like you even less. Because we, we were born Jewish, but you, one of their own, are turning your back on the religion of your ancestors …” The rabbi shakes his head doubtfully. “Your neighbors, they won’t like this one bit.”

“Then we’ll keep it a secret.”

“A secret? How could you? You won’t go to synagogue? You won’t observe the mitzvot? You won’t follow the customs of Israel?”

“Not the Judaism, we’ll keep secret the … the other religion.”

“How is that possible? Does nobody know you here?”

“I’m new in this country. I got off the boat just yesterday.”

“And your parents?”

“Dead.”

“Dead?”

“As good as dead to me. And I’m the same to them.” Silence.

“I want to be Jewish,” Joseph finally says.

“You want to marry a Jew, that’s really what you want!” the rabbi’s son spits.

“True, but nonetheless, I want to be Jewish.”

The old rabbi shrugs and says, “Fine, if not on purpose then by accident. God willing, this will please Him. Where do you live?”

Joseph says nothing. He has no place to live. He certainly cannot stay with his fiancée’s parents.

“The conversion process is long,” says the rabbi. “Stay here, we have plenty of space.” And he turns to his son with a smile. “As it says in the Torah, ‘the foreigner sojourns among you.’”

“I’ll pay you.”

“Are you working?”

“No, but I …”

“When you work, you can pay. The bed doesn’t cost anything, and the food …” the rabbi waved the thought away. “You don’t look like you eat very much, anyway. My wife cooks for three and feeds at least half a dozen. We have two or three guests coming over for every meal. She won’t even notice if she has one more mouth to feed.” Then he laughed mischievously.

“I’ll pay you. How much?”

“Have you got anything?”

“No.”

“Then what are you proposing?”

“How much? I’ll get a loan.”

“Fine. One rial per month, room and board.”

“And for the conversion.”

“The conversion is a mitzvah.”

“How much?”

“Donate to the community. To the poor. As you see fit.”

After the conversion Hakham Ferrera senior married Joseph and Emilie according to the faith of Moses and Israel. Most of the guests, all on the bride’s side, never guessed that Emilie was marrying a former Muslim. Only after years did the cloak of secrecy begin to fray. Suddenly, people began gossiping. How it was found out, no one could say. Among the Hamdi-Alis the matter was never to be spoken of, and none of the suspecting parties dared ask expressly if there was any truth to the rumor. And so the gossip remained hanging between uncertainty and the family’s utter silence.

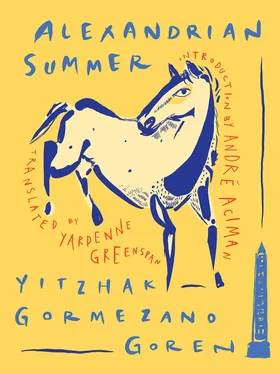

Perhaps this is why Joseph tried, after the marriage, and after leaving Hakham Ferrera’s house, to minimize contact with the old rabbi and his son who succeeded him. They reminded him of the world he’d left behind and wished to erase. With almost cruel decisiveness he severed all ties with his parents, took no interest in their well-being, did not ask when they died or what became of his brothers. He kept only his name. In community records, a Yosef Ben-Abraham was registered, but he himself did not change his heavy Muslim name, the name which pulled him back to his roots. Why did he not change his name? Nobody knew, maybe not even he himself. Soon after they married, Emilie’s father passed away and the young couple, along with the widow, moved to Cairo. Those days, Joseph began making a living riding horses, an activity favored by him since youth. And though the rabbis Ferrera — the father, may he rest in peace, and the son, may he live long and prosper, sitting with him now on the balcony — hadn’t seen him more than three or four times in the many years that had gone by since, a check for two Egyptian pounds, a donation for the community’s less fortunate, arrived at the community offices in Alexandria once a month, every month, for thirty years.

“I need your help,” Joseph repeated. “It’s a matter of life and death.”

The rabbi’s face turned serious. He saw the abysses open, the two wells of Yusef’s eyes, their bottoms too deep to be seen. Yusef was not a joker. Nevertheless, when he thought of his words, the rabbi was embarrassed. A matter of life and death?

“The race is tomorrow,” said Joseph. “Tomorrow — the final race. Then, there’s a break. David will race. He must win. The way that David beat Goliath. Just like in the story, there is more to it than just those two. That’s why David had to win then. And that’s why David has to win now. A matter of life and death.”

A pleasant breeze blew from the sea. The tumult of bathers sounded from afar: Muslims, Christians and Jews desecrating the Sabbath. On the street, cars honked hysterically. The entire city rumbled and roared; nevertheless a Sabbath serenity was felt all around. But the rabbi felt so distant. His late father might have understood immediately, but he thought of himself as a small, insubstantial man. Nothing but a maître de cérémonies , a sort of master of rituals of the synagogue; or, as he once said jokingly about himself, “the conductor of a choir of non-believers.” Everything according to plan, a routine founded in the Jewish calendar, with no unexpected difficulties. But here was a Jew in trouble, and he didn’t even know how to talk to him. “Why?” he asked.

“Why what?”

“Why is this a matter of life and death?”

Joseph held back his impatience. If the rabbi himself did not understand, how could he explain it? This was a matter one either understood immediately or never understood at all. Some people spent their entire life on the surface, in a closed, orderly world, never imagining what might be going on below, in the depths, in those twisting, dark tunnels where lost souls seek their way. A rabbi! A spiritual leader, and he doesn’t know God, the devil, or death. Death! What could be more simple, more quotidian than death? How to explain this to him? Finally, he said with a sigh, “He’s being put to a test, don’t you see?”

“This isn’t the first time he’s participated in a race.”

“Not him. Him. God. God Himself.”

“What test?” Hakham Ferrera said awkwardly. He preferred not to bring God into this affair. The entire conversation seemed out of line, dangerous.

“I’d like you to say a special prayer, Rabbi,” Joseph finally said.

“What do you mean, a special prayer?”

“What — what do I mean?” Joseph railed. “Today, at synagogue, a special prayer for my son to win the race tomorrow.”

“A special prayer for a game of gambling?” the rabbi was outraged.

“This isn’t about gambling, it’s about—”

“Please, show me how this is a matter of life and death. Saving a Jewish soul, there is no bigger mitzvah, but it needs a foundation. You cannot bother God with mundane matters. It’s as if … as if …” The rabbi’s eyes bounced around and landed on the toy train in the darkness of the house, “as if you’re pulling an emergency brake to stop a train midride — an act well-justified in a moment of danger, but entirely inappropriate when there is no peril.” For some reason, Hakham Ferrera was not content with his own analogy. Later, he thought that his heart, at that moment, told him this was not a false alarm. He tortured himself for not having heeded his own intuition. But now, on the balcony, he asked himself what the nature of this distress might be. Yusef Hamdi-Ali had been acquitted, life had returned to its course. Next week the season in Alexandria would end, praised be the Lord, and everyone was already packing up to return to work, school, to the blessed routine that saves most people from purposeless wandering. What did he want? A matter of life and death? It was ridiculous, ridiculous! And nevertheless, Yusef Hamdi-Ali was not a man with a sense of humor. The rabbi squeezed Joseph’s shoulder and assumed his most soothing voice: “What is it, what is it, mon vieux ?”

Читать дальше