Henry Roth

Mercy of a Rude Stream: The Complete Novels

INTRODUCTION by Joshua Ferris

Mercy of a Rude Stream is Henry Roth’s sophomore effort, his follow-up, after sixty years of near silence, to his classic debut novel Call It Sleep . Roth began writing the heavily autobiographical Mercy in 1979 and revised it until his death in 1995; had he lived longer, he would have likely continued writing his life until the two — the writing and the living — had fully caught up to one another. The first volume, A Star Shines Over Mt. Morris Park , was released in 1994; the second volume, A Diving Rock on the Hudson , a year later. The latter two volumes were published posthumously.

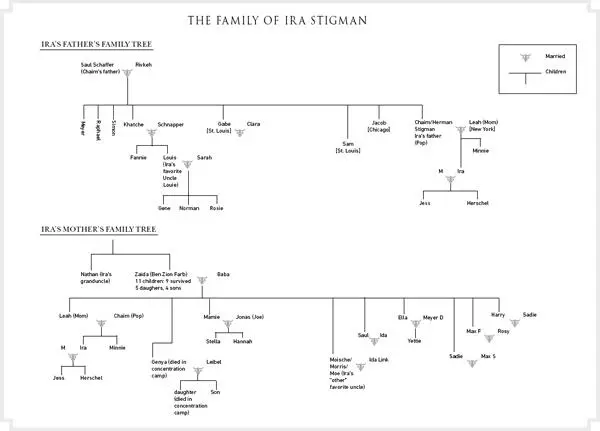

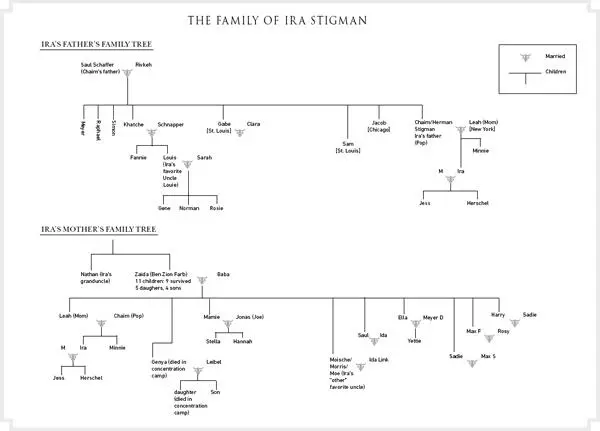

Mercy tells the story of Ira Stigman. Like Roth, Ira was born to Jewish immigrants from Austro-Hungarian Galicia. Like Roth, Ira lived on the Lower East Side of Manhattan as a young boy and suffered when his family moved to Harlem. Like Roth, Ira escapes penury and drift, and squalor, and hopelessness, and mindless toil, and the countless dead ends and cul-de-sacs awaiting even the hardest-working immigrants in “the golden realm,” and makes himself a writer. He succeeds because he’s resilient and shrewd, and because he’s possessed of native literary talent. The culminating event of the novel is Ira’s departure for Greenwich Village: he leaves behind his beloved mother and his tyrannical father and the sister with whom he was incestuously involved for the embrace and nurture of a NYU professor named Edith Welles, the fictional counterpart to Roth’s real-life lover Eda Lou Walton.

Mercy is a rare species of literary epic: an autobiography that doubles as a historical novel. The action of Mercy— set primarily between 1914 and 1927 but interlaced with dispatches from the 1980s and ’90s, and including intermittent reflections of the years in between — encompasses nearly the entirety of the twentieth century: from the outbreak of World War I to the advent of the personal computer. But Roth’s novel isn’t a product of painstaking research; he reconstructed his lost world out of pure memory. Working throughout his seventies and eighties — he lived to be eighty-nine — he filled his bildungsroman with the finely grained details that one can expect only from a firsthand account.

Roth had a brilliant photographic memory. But he wasn’t didactic; he also had the novelist’s instinct. Where fact and fiction begin and end in Mercy is never an easily discernible divide. The basic outline of Ira Stigman’s life as chronicled in the book — his development through adolescence and into his young adulthood — closely mirrors that of Henry Roth’s. But if Mercy is largely shorn of the Joycean artifice of Roth’s earlier book and pointedly tries to narrate life as it was lived, Roth happily sacrifices biographical truth in Mercy to the more pressing emotional one that had revealed itself to him decades later. There’s little doubting the detailed accuracy of his reconstructed Harlem, or his rich evocation of immigrant life in New York City in the first decades of the last century, but the embellishments are there to serve Roth’s hard-fought artistic purpose.

And it was hard-fought. After writing Call It Sleep, Roth floundered. By the time of that book’s publication, in 1934, he was deeply committed — as many on the American left were in the 1930s — to the communist ideal. He was internally riven by the need to square his “bourgeois” talent for detailing the rich inner life of the individual with the proletarian dictates of socialist art. He was badly affected by his first book’s reception in left-leaning periodicals, and was determined to write something the Party would be proud of. With an advance from Maxwell Perkins, who admired Call It Sleep , he set out to do just that, but failed. Thereafter he worked, as a good communist must, various hard-scrabble trades. He started a family. He squandered time and fell out of sight. It would take a profound disillusionment with Soviet communism and a long personal reckoning before Roth would seriously take up writing again, only to conclude, after so long and so much trouble, that he only ever had one subject: himself.

An omnibus edition of Mercy is an exciting event, a chance to introduce it to a new generation of readers. But even old readers need to take a new look, now that the sweeping scope of Roth’s work has been fully contained between two covers.

Mercy was originally published as four separate books. The first, A Star Shines Over Mt. Morris Park , was artistically the least successful of the four. It’s likely that Roth had trouble finding the right balance, the right pacing, the right rhetorical and fictional tactics with which to begin his monumental undertaking. There was much to do in that initial salvo: introduce Ira, his parents, and their extended family; introduce as well a latter-day Ira who lives with his wife, M, in Albuquerque and who discourses with his computer, Ecclesias, on the challenges of composing a book identical to Mercy ; establish a dialectic between these two Iras — typographically, rhetorically, circumstantially, and philosophically distinct, and separated in time by nearly seventy years — that would come to shape and inform the following three volumes; re-create a bygone world of Yiddish-speaking immigrants ensconced in a vanished Harlem with all its thrumming, threatening vibrancy; situate that world within the larger context of the First World War; and convey to the reader Ira’s personal drama: his crushing solitude, his aimlessness, his sensitivity, and his nascent gifts as a writer. Henry Roth was seventy-three years old when he began the book and had been more or less blocked for the previous forty years. He was racing against time and in declining health. To be writing again, indeed to be redeeming his life by writing it, must have felt like an extraordinary relief almost indistinguishable from panic.

As the epic begins, we first meet Ira as an eight-year-old boy. He has just moved from the Lower East Side, where life passed by in an unconscious blur because he was surrounded by fellow Jews, and because he was so young. The Stigmans move as far north as 108 East 119th Street — some blocks north of Harlem’s Jewish enclave — because cold-water flats can be had cheaply there, and Ira’s father is a wickedly parsimonious man. The new dwelling also has a front window, which is especially important because Ira’s mother has depressive tendencies and relishes the light and the view. But for Ira, the move is nothing short of exile from Eden. Hostility in goyish Harlem awakens the boy from his daydreams; “Irishers” rule the street, and scorn, even in that slice of melting-pot America, is reserved especially for the Jew.

At the same time that he’s awakening to the inevitability of being “a lousy Jew,” as the Irishers would have it, and in his wish for assimilation, he rejects his all-too-Jewish extended family. They have arrived at the outbreak of the war, fleeing not only international hostilities but the pogroms that made daily life for European Jewry an unrelieved nightmare. Ira hopes to find in these new arrivals the kind of people he left behind on the Lower East Side — protectors, mentors, and friends. His kin, he hopes, will be “bountiful, endowed with a store of beguiling anecdotes, with rare knowledge of customs and places which they were only too happy to impart on their doting little kinsman. In short, they would somehow be charmingly, magically, bountifully pre-Americanized.” Instead, he encounters:

Читать дальше