There is a silence. The music is followed by applause, then the Korean commentator launches into a dense monologue, without pausing, in which neither Yasar nor Freek is interested.

“Sky burials. .” Yasar says thoughtfully. “A very, very ancient custom, it must go back to prehistoric times. I’ve heard about it, but I didn’t know it was still practiced. I’d have never guessed that it could happen here, in the middle of the city. Today. Just a kilometer from here.”

“There are rules,” says Freek. “You have to be patronized by the group, the lamas have to give their permission. And you especially need authorization from city council and written consent from the zoo director. But the vultures aren’t asked for their opinion. The vultures don’t really cooperate. They’re afraid of people who come into the aviary and throw clown meat at them. They don’t like to eat circus artists. I’ll have to speak calming words to the vultures too. I’ll go to the aviary later.”

“This clown, do you know any more about him?” Yasar asks.

“He killed himself,” says Freek. “There were two of them on the bill, always together. Blumschi and Grümscher. Blumschi and Grümscher, the kings of laughter. One small and one big. I went to see them in their circus, last month. It’s losing speed, a poor circus with a poor public. The clowns take the floor between numbers and speak loudly. They shout, they gesticulate, they lose their balance. They speak into the void. There aren’t many people on the bleachers. The audience is bored. They’re waiting for the trapeze artists, they want to see a trapeze artist’s skeleton shatter on the sawdust-covered ground. They’re waiting for the tamer, they want to witness an accident with the bears, they want a bear to tear an arm off the tamer or his daughter. They’re not amused by the clowns. No one’s laughing. I laugh, but that’s because I’m not. . because I’m different. . I laugh, but no one else does.”

The commentator continues her short speech. She does it softly, but all the same everyone would like her to wrap it up, to put the mic down and bring the music back. It’s a live radio broadcast. On the other end, the commentator is facing the public, and the public appreciates her banter, her flattery, the public smiles loudly or applauds when she wants them to. She is like an animal tamer, the obedient audience grovels before her voice and desires to show that they’re under her spell. She finally shuts up, the audience applauds once more, and there is a blank in the broadcast, perhaps because the musicians left the stage and have been sitting down. At the same moment, during the blank, a Buddhist voice can be heard.

“You hear that, Yasar?” says Freek. “A religious service on the other side of the wall.”

“Yes,” says Yasar. “It’s coming from next door. It was a dilapidated garage. Old car doors, grimy motors, cans of oil. Red Bonnets converted it into a temple. We have an adjoining wall. It was already thin, but with the renovation work I think it’s gotten even thinner. Some days you can hear everything. On top of that we share an air vent. Noises pass through it.”

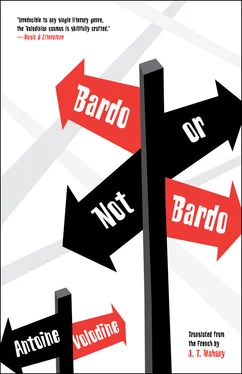

“They’re about to begin a ceremony for the deceased. A lama is going to read the Book of the Dead . He’s going to speak to someone who died recently. He’s going to give them advice to help them not be reborn as an animal.”

“So you’re a religious expert now, Freek?”

“Not really, no. .”

They listen to the noises coming from the temple. Not much can be heard, actually. A solemn voice, now and then. Not much. Now, the Korean music has returned, a very long piece with syncopated drums and a magnificent soprano voice. Since the radio’s sound is very low, not much can be heard from over there, either.

“It’s sad,” says Yasar after several dull seconds, “thinking about clowns who can’t make anyone laugh.”

“Out of everyone on the bleachers, I was the only one who did,” says Freek. “The spectators watching looked like they didn’t understand a thing. Even the children’s eyes were blank. They barely reacted at all. I was the only one who found them funny. Maybe it’s because I’m not a person. Well, I mean, not a real person. .”

“Hey, Freek! What are you talking about? Of course you’re a person. This isn’t because you. .”

The bartender doesn’t continue. He doesn’t feel like getting mired down in unsettling considerations, he doesn’t want to think aloud about what parts of humanity Freek is lacking. Yasar the bartender’s culture has always been resistant to racism, he has always refused to give in to atavistic urges to reject the Other, he has never felt the need to classify Freek in a disparaging animal category, himself being considered a sort of Untermensch, but he prefers not to think about those things aloud in front of Freek. He turns back toward the percolator, he wipes the wall, he rummages through the basket of cutlery.

“Of course you’re a real person,” he repeats.

A car passes by, the windows tremble in their frame. The lamas’ voices come through the partition. A second car passes by, the driver accelerates, he strains his motor without changing speed, the windows shake.

The door opens. A client enters, not a regular: someone unknown, short in stature, dressed like a Sunday proletarian, with a full jacket too long in the sleeves. He has gray hair, a worn-out expression that the lack of sleep has rendered cartoonish.

“Good evening, gentlemen,” he says.

His voice lacks confidence.

He goes to sit at a table under a fluorescent light, three meters away from the counter. Freek and Yasar greet him, but don’t look at him, Yasar out of professional tact, Freek out of shyness.

“You wouldn’t happen to have any salted buttermilk tea, would you?” the newcomer asks.

“No,” says Yasar. “We don’t have that here.”

“I was joking,” the man explains.

“Oh,” says Yasar.

“Two whiskeys,” says the man.

“A double?”

“No. In two glasses. Two doubles. With very few ice cubes.”

Yasar disappears the dishcloth he had on his shoulder and gets to work. No one says a word. There’s the sound of falling ice cubes, pouring alcohol, the temple bell, the radio. The pansori singer can be heard. Yasar places the glasses on a platter, and brings them to the small man’s table. Then he takes his place back in front of Freek. For twenty seconds, they don’t speak, both of them, as if the presence of a client behind them is preventing them from picking back up the interrupted conversation. Then Yasar shakes his head.

“You know, Freek,” he says. “In my opinion, they’re exploiting you, over at the zoo. They know very well that you’re going there after hours and taking care of the animals. What you’re doing is still work. Night work. They should compensate you.”

“Oh, I do it for the animals, not to get dollars,” says Freek. “And anyway, they pay me. Some days the director makes me come into his office. He talks to me. He gives me papers to sign. I sign them with my name. He gives me free meal tickets for the watchmen’s canteen.”

“There’s no way they count all your hours,” says Yasar. “I’m sure they’re exploiting you, Freek.”

“No, they do me right. Of course, sometimes. .”

“Sometimes what?”

“Oh, nothing. .”

“You were going to say something, Freek.”

“No.”

“Something that bothers you.”

“Well, sometimes they mistake me for an animal,” says Freek. “The watchmen. It’s an accident, I think. Not out of malice. They grab me on one of the paths before opening time. They don’t listen when I protest, like I’m talking to deaf people. No matter how loudly I complain, they open an empty cage and close it again with a padlock. Next to me they put cold food and some straw for toilet paper. There’s a sign hung from the bars: PLEASE DON’T FEED THE ANIMALS. While the zoo’s open to the public, I keep away from the sign so people don’t think it’s talking about me. At any rate, I don’t get much. The guards leave me there for three or four days. Then, they free me. They apologize. They say it was a truly regrettable mistake, that they accidentally got me confused, and it wasn’t out of malice. They say that I look too much like an animal. That they weren’t paying attention, because I’m tame, and I talk instead of biting or scratching. . You see, Yasar? I’d have to bite them for them to see that I’m something other than. . With all that, Yasar, how should I know that I’m really a person?”

Читать дальше