He doesn’t know what to say. And yet something must be said — anything at all — even if it’s inappropriate, even if it will never be as beautiful as what Juan Ramón has written in his poem. For example, he could tell his friend — friend? — that over time he has almost entirely forgotten the women they seduced back then, the games they used to play to amuse themselves, the poems they wrote or read together, the voice of his dead father, but that nevertheless he remembers Georgina’s face in the minutest detail. But he cannot tell him that, because it would be, in some way, like starting the novel over again, and all he wants is to finish it once and for all. Close the book. Finally reach the last page, and then keep on living.

And for that they need only to write the ending, an answer to the question that the Maestro poses in his poem. And he decides to do that right there, in that blank space, just below the final line: Carlos Rodríguez. A slow, laborious signature that tears at the paper, as if instead of scrawling his name he were carving an epitaph. And in spite of everything, José doesn’t understand at first, and Carlos has to explain it to him again, once, twice, attempting to pass him the pen, to hand back the book: It’s our life, he says, this is the best thing we’ve ever done, the best thing we’ll ever do, so now we’re going to sign it. It seems like a joke, and when he hears it, José laughs. But it’s not a joke, it’s the ending to their novel — quite a serious matter — and when he finally understands, his expression grows sober, concentrated. He, too, takes a long time to sign his name. He, too, is careful to make it a good signature, the one he uses for checks and formal documents.

Then they pay the bill and walk together three or four blocks to the corner where their paths diverge. Maybe they chat about something else before saying goodbye. They may try to lighten the dramatic tone of their parting, the solemnity of their names interwoven on the page of the book of poems. They will spend the rest of their lives doing that: pretending that the ending has not yet arrived, that a great many things are still to come, that what succeeds that poem and that novel still matters. But they will do all that on their own, once more on their own. Because when the last chapter is over, they will never see each other again. That, then, is their ending: a poem, two signatures, a farewell.

◊

They part on the very corner in San Lázaro where their garret once stood. Like all coincidences, this one is meaningless, but on his way home Carlos amuses himself by coming up with different explanations.

It is a new brick building with freshly painted bars on the windows and electrical wires running up the walls. He stops and looks at a particular spot on its façade. A place where, in fact, there is nothing to see, somewhere between the third and fourth floors. His memory has to painstakingly rebuild the rest: a crumbling attic, a roof with splintering rafters, a window. Two young men looking down from on high. And it seems to him that if his nearsighted eyes were twenty years old again, he would be able to see their hats and bow ties, all from another era, and, of course, their ridiculous mustaches; and that if it weren’t for the automobiles and the honking horns, he could even make out what the two men are saying to each other.

“And what about that fellow?”

“Which one?”

“The fat one… the one looking up at us. The one stopped in the middle of the street, carrying a book under his arm.”

“Oh! Well… he looks like a portly millionaire out of a Dickens novel, don’t you think?”

“To me he looks more like a bored middle-class man from one of Echegaray’s plays.”

“Or a greedy landlord out of Dostoyevsky, with the addresses of all the tenants he’s going to evict written in that little book.”

A silence.

“Not at all! Take a good look. Now that I observe him more closely, I think he’s really just a secondary character…”

And down there on the sidewalk, the millionaire, the landlord, the secondary character, looks back at them and smiles.

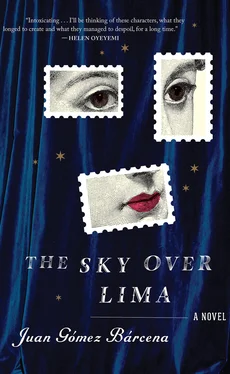

Letter to Georgina Hübner in the Sky over Lima by Juan Ramón Jiménez

The Peruvian consul tells me: “Georgina Hübner is dead…”

… Dead! Why? How? On what day?

What golden rays, departing from my life one eventide,

would have burnished the splendor of your hands,

so sweetly crossed upon your quiet breast

like two lavender lilies of love and sentiment?

… Now your back has felt the white casket,

your thighs are now forever shut,

and in the tender green of your new-dug grave

the sinking sun will set the hummingbirds aflame…

La Punta is much colder and lonelier now

than when you saw it, fleeing from the tomb,

those far-off afternoons when your phantom told me:

“So often have I thought of you, my dearest friend!”

And I of you, Georgina? I cannot say what you were like—

fair? demure? melancholy? I know only that my sorrow

is a woman, just like you, who is seated,

weeping, sobbing, beside my soul!

I know that my sorrow writes in that graceful hand

that soared across the sea from distant lands

to call me “friend”… or something more… perhaps… a part

of all that throbbed in your twenty-year-old heart!

You wrote: “Yesterday my cousin brought your book to me.”

Remember? Myself, gone pale: “A cousin? Who is he?”

I longed to enter your life, to offer you my hand,

noble as a flame, Georgina… In every ship

that sailed, my wild heart went out in search of you…

I thought I’d finally found you, pensive, in La Punta,

with a book in your hand, just as you’d told me,

dreaming among the flowers, casting a spell on my life!

Now the vessel I will take one evening, searching for you,

will never leave this port, nor cleave the seas,

it will travel into infinity, its prow pointing ever upward,

seeking, as an angel would, its celestial isle…

Oh, Georgina, Georgina! By heaven! My books

will wait for you above, and surely you’ll have read

a few verses aloud to God… You will tread the western skies

in which my fervent fancies are snuffed out…

and learn that all of this is meaningless—

that, save love, the rest is only words…

Love! Oh, love! Did you feel in the nights

the distant thrall of my ardent cries,

as I, in the stars, in the shadows, in the breezes,

wailing toward the south, called out to you: Georgina?

Did, perhaps, a gentle zephyr bearing

the ineffable perfume of my formless longing

pass by your ear? Did you hear something of me,

my dreams of your country estate, of kisses in the garden?

Oh, how the best of our lives is shattered!

We live… for what? To watch the days

with their funereal hue, no sky in the still waters…

to clutch our foreheads in our hands!

to weep, to long for what is ever distant,

and never to step across the threshold of dreams.

Oh, Georgina, Georgina! to think that you perished

one evening, one night… and I all unknowing!

Читать дальше