Their poverty softens them while the reverie lasts, which isn’t long, as daydreams are arduous things that can be sustained only with immense effort. Lima is a place that is impervious to fantasies, and soon they feel the heat of their eternal summer once more, or they notice a gold cufflink gleaming at one of their wrists. Or perhaps the Rodríguez car noisily invades the unpaved streets and the chauffeur pokes his head out the driver’s-side window and shouts, “Master Rodríguez! Your father wants you home for dinner!” Then their dream plunges downward like the coin they’ll never toss into the Seine, and suddenly they see themselves again for what they really are: two wealthy young men looking at poverty from on high.

“What a God-awful city,” murmurs José as he prepares to go down.

◊

But their favorite pastime is the character game. It began by chance during a lecture on mercantile law, when José observed that the professor looked just like Ebenezer Scrooge, right down to his spectacles. They both tittered so loudly that Professor Nicanor — Mr. Scrooge — interrupted his lecture and escorted them to the classroom door, whose threshold they seldom darkened anyway. Out in the courtyard, fortified with alcohol, they continued playing. The Roman law professor was Ana Ozores’s cuckolded husband from Leopoldo Alas’s La Regenta . The ancient and practically mummified rector was Ivan Ilyich before Ivan’s death — or perhaps, José added snidely, Ivan Ilyich after his death. The widow of the impresario Francisco Stevens, an extraordinarily fat woman, was an aging Madame Bovary. “But Emma commits suicide when she’s still young,” Carlos objected. “Exactly,” Gálvez countered. “She’s a Madame Bovary who doesn’t commit suicide. One who has the objectionable taste to outlive her beauty and become fat and farcical.”

Soon enough everyone’s a character: friends, relatives, literary rivals, strangers. Even animals: though they’ve never seen the cat that ekes out a living in the garret — they occasionally hear it yowling somewhere amid the detritus, perhaps reveling in the knowledge of being among kindred spirits — they are unanimous in their conviction that it belongs in a Poe story.

From up on the rooftop, they decide with unhurried capriciousness which of the people swarming at their feet are the work of Balzac, or Cervantes, or Victor Hugo. Up there it is easy to feel like a poet, to contemplate the square and the adjoining streets as if they were a vast postcard with characters from all the world’s literature wandering about. For example, the first fantasies of the schoolgirls who line up at the entrance to the convent school are written by Bécquer. The lives of the wealthy citizens striding across the square are narrated by Galdós — what dull lives they lead, poor things, just like Benito the Garbanzo Eater himself. If you are one of the whores on Calle del Panteoncito, your endless misfortunes are narrated by Zola or, should you become a nun, by Saint John of the Cross. The drunks who stumble out of the taverns, of course, are figments from the nightmares of Edgar Allan Poe. Madmen? Dostoyevsky. Adventurers? Melville. Lovers? If things turn out well, Tolstoy, and if they go sour, Goethe. Beggars? That’s an easy one, because poverty is everywhere alike — the lives of Lima’s mendicants are written by Dickens, but without fog; by Gogol, but without vodka; by Twain, but without hope.

An implacable arbitrariness also divides the characters into protagonists and secondary figures, and their deliberations on whether or not a particular beautiful woman or a certain picturesque beggar is the main character of a story can go on for quite some time. The matter is not to be taken lightly, as protagonists are, in fact, a rare breed; you have to stumble across them, track them patiently amid the mob of figures entering and leaving that page of the book of their lives.

What would they say if they saw themselves strolling across that square? With what writer would they associate their own footsteps? Would they consider themselves secondary characters or protagonists? These seem like natural questions, ones they should have been asking all along. Strangely, though, they never have. Perhaps it hasn’t occurred to them. Or perhaps they feel that their place is somehow there, not on foot in the street but on high, up on the rooftops of other men’s lives.

It is an odd game — a frivolous one, even — but, in the end, a fitting one for young men who see literature everywhere they look, for whom everything that happens around them happens just as they’ve read in books. Indeed, it would hardly be surprising to discover that this very scene — two men who, from their garret, dream of commanding the entire world — also came from one of those novels.

◊

Lima, June 26, 1904

Señor Jiménez:

Immediately after posting my letter requesting a copy of your Sad Arias , I wished I could retrieve it, destroy it utterly. Why? I shall tell you: I imagined that my behavior was rather unseemly for a young lady. Without ever having met or even seen you, I wrote to you, spoke to you. I was so audacious as to impose upon you, to ask a tedious favor of you, you who are so generous and yet owe me nothing…

I reproached myself for all of this again and again until I was in agony. When one is twenty years old, as I am, one thinks quickly and suffers deeply!

Yet all of my inquietudes were soothed, all my doubts evaporated, when I received your kind letter and your beautiful book.

Your mournful verses speak to the heart with the resonant cadence of Schubert’s melancholy melodies. I will long remember these stanzas, through which wafts the delicate, gentle perfume of the author’s soul.

If I told you that I liked one part of your book better than another, it would be a falsehood. Each part has its own charm, its gray tone, its tears and its shadows…

I must tell you that, since reading them, I have been haunted by many of your verses. I seem to recognize all around me the gardens, the trees, the longings that you describe in your poems. As if it were here, on this side of the ocean, that you endured and enjoyed such exquisite sentiments.

Do you not also, when you look upon the world, feel that it is made from the stuff of literature? Do you not seem to recognize in passersby the characters from certain novels, the creations of certain authors, the twilights of certain poems? Do you not feel sometimes that one might read life just as one turns the pages of a book…?

◊

They want to be Juan Ramón Jiménez.

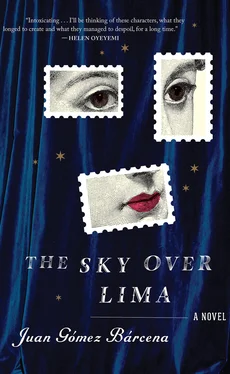

In a drawer in his desk, José hoards each letter, each stamp moistened by the poet’s precious saliva. Five handwritten poems. Two signed portraits. A book inscribed in purple ink— with the most sincere affection —to young Señorita Hübner of Lima. Luckily, Carlos has not attempted to claim any of these trophies, as José must have them all for himself. He can no longer sit down to write a poem without first touching the page upon which, even if just for a moment, the fingers of Juan Ramón once rested. The pen that scrawled Violet Souls when its author was precisely the same age that José is now. So young! This is the moment, he tells himself, stroking the watermarked paper as he might caress a woman’s skin. And then he waits, sitting at his desk. He grasps his pen firmly, waiting for something to happen. But it never does.

Carlos is amused by the worshipful way that José collects every tiny scrap of Juan Ramón’s life with philatelic patience. Yet despite his amusement, of course he does not mock. That is a privilege reserved for José alone. Though Carlos is the one who writes the letters, his objective in doing so is not to obtain those sacred objects. He is unmoved by the thought of an advance copy of the Maestro’s next book, Distant Gardens , which Juan Ramón has promised to send. Carlos pretends to be Georgina for a different reason altogether, though if anyone asked him what it was, he would not know how to answer.

Читать дальше