Peter Pišťanek - The End of Freddy

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Peter Pišťanek - The End of Freddy» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2008, Издательство: Garnett Press, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

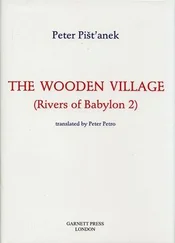

- Название:The End of Freddy

- Автор:

- Издательство:Garnett Press

- Жанр:

- Год:2008

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The End of Freddy: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The End of Freddy»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The End of Freddy — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The End of Freddy», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

* * *

Despite the prisoners’ disparaging comments, the Belgian hostage managed to escape. In the harbour he hid himself on the roof of a warehouse and waited for the next ship. It was a ship taking a cargo of lichen to France, the perfume superpower. The Belgian crawled deep into the load of lichen. He could breathe well through the porous material and it kept him warm, too. Once in France, in Le Havre, starved almost to death, he reported to the authorities. At first nobody would believe him, but eventually the whole world found out the shocking truth about the Kandźágtt camp on the Junjan island of Ommdru.

After the visit of a Swedish representative of the Red Cross, interned foreigners are not allowed to work. But nobody has forbidden taking them with other prisoners to the moss-gathering zone. And so every day, they take them to taiga and let them stand all day long up to their knees in the snow and storm. Old and new prisoners come to know each other really well. Moreover, they are closely bonded by mutual knowledge of the secret of the violent death of the grass Fridrych, who was about to run to the guards’ barrack to betray Doložil’s identity, since he knew the real Doložil personally from Prague. Freddy caught up with him on the way. Fridrych the grass slipped and was unlucky enough to fall and fatally break his head on the barracks wall. Then Freddy recalled Rácz’s words: once a man kills another man it’s like a window opening in the middle of his forehead and nothing will ever be the same as before .

In other prisoners’ eyes, Freddy’s reputation grows even more after this act. They respectfully call him by a name that first slipped from his lips in a moment of shock. For all of them, he was Telgarth from then on.

Hostages whose ransoms are still unpaid spend whole days in the snow. In the evening, they’re taken back to the freezing barracks with the ordinary labourers.

The cold is vicious. There’s not a living thing anywhere around. Everything has either frozen up, or migrated to warmer coastal areas.

Agapp comes to check the prisoners. He looks around in hatred, as he’d like to try his new whip’s resilience on the foreigners. He can’t understand the new era, and has no idea why foreigners don’t have to work. Under the Soviets they had to. Once a commercial Canadian aeroplane made an emergency landing in Junja, and before they ascertained that this was not a case of espionage, the captured foreign passengers had to go to the camp and work, too. The guards kept a stewardess for entertainment, even after they handed back all the others. They just declared her dead. Some Canadians couldn’t take it: what do you expect? The foreign woman was lent to the harbour guards, but they didn’t watch over her during their orgies: she ran naked into the sea. She was found a few days later, drowned, tossed ashore by the waves.

And why has the chief forbidden beating foreigners until they cry? Doesn’t a foreigner deserve to be beaten just for being foreign? When a foreigner’s ransomed, he goes back to his world to loll in warmth and luxury while the bosses up here divide the dollars among themselves. But Agapp will freeze forever in the work zone. What an injustice!

Agapp spits angrily, and his spit freezes on his collar. Only his angry slanting eyes look out from under the fur. He remembers the old times. Soon he sets out to herd other prisoners, those gathering lichen. Some of them will feel his harsh, casual, but precise blows of the whip.

Freddy Piggybank is used to the magic mushrooms even though his ribs healed long ago and he has no more pain. Today he found a new supply under the snow, enough for three or four fixes. Now he feels good and has no pangs of cold or hunger. His thinking has accelerated. He almost feels pleasure. He watches the women. They climb over the rocks, scraping off the green-grey cover. They are dressed in thick quilted clothes that give them a stout, mannish look. They look like the television record of the landing on the Moon. They, too, move clumsily like astronauts and scrape at rocks with the same care.

Freddy can’t even remember when he last had an erection. Even though, as an interned foreigner under Red Cross protection, he doesn’t have to work, he is somehow constantly sleepy. He can even sleep on his feet. It may be the mushrooms. Looking at the emaciated women, who defecate when they need to right in front of his eyes, does not excite him at all. Freddy is a civilised man. For him sex has to be served up æsthetically. It has to have refinement: make-up, perfume, stockings, and garters: in short, it has to be served with all the sauce that goes with it. Mutual rubbing of mucous membranes is the last thing, and even at the peak of his sexual activity Freddy did not really require it.

He’s quite unaware that whatever comes to mind he says out loud.

Blažkovský thinks that it was addressed to him. He agrees with Freddy. He’d rather have his prick cut off rather than screw one of them.

Freddy understands that. As one man to another, he can say that even back home, in Bratislava, not everything was to his liking. Some women were dressed even worse than here, in the camp. Freddy hates especially the new disgusting fashion. Those shapeless shoes. Women walk in them as if they had a brick tied to each foot.

“And those horrible acrylic sweaters two sizes too small!” Ondrejka joins in after stomping the snow nearby.

One thing is for sure: Ondrejka hated that fashion when it appeared for the first time in the seventies. Every young woman now wants to look like a dirty drugged whore. And with that pathetic backpack on, she looks as if she is perpetually hiking.

Doložil has no opinion on these things. He listens in silence. He can’t fully understand everything anyway. He remembers times when he would return from a hunting trip and his good wife would let her hair down, light five lamps, undress and warm him with her body. Warmed up and revived by her hot skin, he would enter her and make love to her. He had no idea what these men were talking about, all that painting and dressing up. What painting? Real beauties are tattooed, after all. And these men? They’re like women talking about softening reindeer skin in the women’s corner of the yurt. Men are supposed to talk about hunting, fighting, trade, long journeys, escapes, not about women’s boots!

One of the women lichen gatherers seems too slow for the woman guard. The prisoners watch the guard greedily attack her with a whip. The female prisoner tries to escape, but in vain. She slips and falls with a thud into the snow. The female guard kneels on top of her and beats her all over. The prisoner can’t feel much pain through her coat’s quilted layer, but she screeches even more. Finally the guard hits her in the face, her only unprotected place and the prisoner, bleeding badly, grows quiet.

Blažkovský also hates those shoes. They are formless and disgusting. They make women’s legs look grossly thick. Blažkovský likes women in classic pumps with medium to high heels. A woman should walk like a gazelle and not like Frankenstein’s monster.

The female guard calls for a colleague. Together they try to put the obstinate female prisoner back on her feet and make her walk.

“But a heel should not look like a hoof,” Ondrejka emphasizes.

“Definitely not,” agrees Blažkovský. “It has to be a thin stiletto heel. And at least eight centimetres high!”

The female prisoner doesn’t want to come back to life. She drags her feet powerlessly behind her. Tracks of blood lie in the snow. The guards drop her onto the ground and leave her lying there. Other prisoners have interrupted their work and watch everything. Whips in hand, the guards hurl themselves at them and force them back to work.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The End of Freddy»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The End of Freddy» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The End of Freddy» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.