But it was decreed that I had to push my head against that rock and make that pocket of earth into a great whirlpool.

That was done.

What are a thousand stags in the wheels of the world?

THE SARDINIAN. Tell me, River.

Did you encounter man?

THE RIVER. I encountered what he left.

Here it is:

You know that I’m made of sky; you can believe me. In descending from the mountain, I got tangled up in a large forest and for a long time I looked for my proper course, and I slept there, laid flat, under the trees, and I was eaten by the big green flies.

There, I remained a long time, my muscles building up for nothing. Everyday, my flesh swelled a little more all along the length of my skin, but that was all.

The trees lay over me; long grasses pushed through me as through a dead snake and I began to smell bad.

It was a mountain forest and, from one place, it leaned over the steps of the mountain.

When I learned that, in the fold of the grass, I inflated my head. It became round and glistening, and all my weight, all my strength inflated my head. It became like one of those big drops which are the stars; it weighed down, it tore itself away, and finally it made the leap toward that wide hillocky plain, greenish-gray as an old cauldron, and my whole body followed.

During the leap, I saw the great herds of beasts running and, there in front, a beast who walked on its two hind feet.

And I threw out my huge arms from all sides and I ripped out great trees by the fistful, and I saw wolves who climbed into the oaks and chamois who ran in the flat grass with the regular trot of horses, heavy bears who leaped, like bubbles, over the marshes, mares and forests of foals so thick you could only see their backs and heads, and all of that trembling like leaves in the wind.

And I forced myself to catch up with a wide forest that fled before me. There were branched stags and so many does they seemed like clouds pushed by the wind. At the end of the world there was a high red hill and it barred the route and I hit it with all the strength of my white forehead and my idea.

It was to this that the Sea referred earlier with her bitter words, typical of those who have green lips and tongues of salt. It’s true, I made the great forest of stags drink, but listen, Sea, and learn, Sea, what the law is, and the good balance:

They turned toward me, and head to head, we battled.

Me, with my soft blue head. Them, with their heads of stone and those pointed branches that spread out above them like the branches of oaks.

And I began to climb over the does and the fawns, softer than the limp new branches of the fig tree and I packed all that under me till I felt the quivering of its blood.

Finally, from the height of this platform, I attacked the stags and I retreated, then I hit with my whole head, and, each time, I was torn open, and the water ran between the deers’ antlers and they shook their heads with anger, and they bared their teeth and bit into me, and everything was a chaos of spray and sweat.

And then, I felled them like huge trees, and in my depths, they became mud.

That’s the law.

Am I the one who will teach you, Sea, what mud is, you who saw your bitter greenness flower with life, at the time when life descended upon the earth like a seed, at the time when earth entered through that door of the sky into the regions where life is permitted. You who saw that bitter mud of your shores lift like the back of a serpent and toss to bits all the creatures of the world. 8

Earth!

It was one evening.

And I had no more anger, no more fight, and I was flowing.

It was evening; in peace I crossed a large blue forest and the whole sky sang our two songs.

On one of my sloping banks, there were the tracks of beasts. And, in the midst of them, the tracks of man.

THE SARDINIAN (He raises his hand to stop the cripple). Stop, River, stop!

Ah!

Repeat what you said: the tracks of man were in the midst of the tracks of the beast?

THE RIVER. Yes.

Wide tracks that went off into the woods.

THE SARDINIAN. I’m lost, that’s my death.

That’s the death of me, the living earth!

No longer will I be this big beast sprawling in the sky.

But I’ll be put to pasture like the cow.

If man has become the master of the beasts.

Speak!

THE RIVER. I don’t know.

I saw that image of feet that pierced the mud here and there and entered the woods.

But I couldn’t follow.

Ask the Tree.

So here we are in pursuit of man. Here we are in pursuit of that primary position held by the Sardinian.

For right now, I’m not going to translate the rest of the play. I only wanted to give a long series of scenes to show how the serpentine action unfolds. Furthermore, it does not form a whole, a round fruit well sealed off from the sky all around, but it is, on the contrary, like a soft fig, too ripe on one side, its honey dripping gold, and on the other side, bitter and creamy with the milk of the tree, because the shepherds don’t all have the same poetic powers, and in the best flow, there is some water without taste.

As for the Sardinian’s prime place, it will be threatened throughout by the Sea. Glodion will have his say from time to time and each time, it will brutally interrupt the Sardinian’s inspiration. So that finally he will be told:

O Sea, made jealous by all your salt;

Of all this salt that burns your skin,

Jealous of all the greenness.

Leave us in peace.

It would be a beautiful world indeed if it was made up only of you,

We would be soft as an egg without a shell,

And you would lose your fish in the sky

All along your course.

To tell the truth, as for the Sardinian’s primary position, that power that launches the drama like gunpowder, no one wants to see it taken away from the one who holds it. Except for the cripple who did the River, the other shepherds are not up to it, and never will anyone say anything that can compete with the opening monologue, which I call “the birth and youth of the earth.” Even the cripple has faults. He can only improvise in a trance, in a sort of fever that makes his eyes glow in a wind that thrashes him about, limbs strewn. The Sardinian remains motionless as a column. He only moves for the greetings. From this stillness flows a great nobility and when, at the end of the drama, remaining alone, he makes a few essential gestures, they go to the height of tragedy in a single bound.

So here is the pursuit of man.

The Tree arrives. It says what it sees from the top of its head:

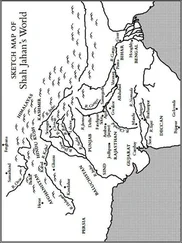

From the shores of that river

to the red tree

and beyond more than twenty hills which mount each other like rams and ewes.

It indicates man’s route, that track in the grass: like the slime of a slug. But from the red tree on, it loses sight of it.

But, there’s the Wind and here it comes with a leap. The Wind, at the end of one of its courses, has encountered man and has accompanied him because it has found him:

. . not at all thorny

and supple as silk, and very light on the two springs of his legs.

And his arms are like two wings that tickle without beating me.

Читать дальше