JEAN GIONO (1895–1970) was born and lived most of his life in the town of Manosque, Alpes-de-Haute-Provence. Largely self-educated, he started working as a bank clerk at the age of sixteen and reported for military service when World War I broke out. He fought in the battle of Verdun and was one of the few members of his company to survive. After the war, he returned to his job and family in Manosque and became a vocal, lifelong pacifist. After the success of Hill , which won the Prix Brentano, he left the bank and began to publish prolifically. During World War II Giono’s outspoken pacifism led some to accuse him unjustly of collaboration with the Nazis; after France’s liberation in 1944, he was imprisoned and held without charges. Despite being blacklisted after his release, Giono continued writing and was elected to the Académie Goncourt in 1954.

PAUL EPRILE is a longtime publisher (Between the Lines, Toronto), as well as a poet and translator. He is currently at work on the translation of Jean Giono’s novel Melville (forthcoming from NYRB) and lives on the Niagara Escarpment in Ontario, Canada.

DAVID ABRAM is the director of the Alliance for Wild Ethics. A cultural ecologist, philosopher, and performance artist, he is the award-winning author of Becoming Animal: An Earthly Cosmology and The Spell of the Sensuous: Perception and Language in a More-Than-Human World . He teaches and lectures around the world and lives with his family in the foothills of the southern Rockies.

All of man’s mistakes arise because he imagines that he walks upon a lifeless thing, whereas his footsteps imprint themselves in a flesh full of vital power.

— JEAN GIONO

THIS TRANSLATION of Jean Giono’s Colline goes to press during a time of rapidly intensifying ecological disarray. More and more species find themselves plunged into extinction by the steady surge of human progress, while seasonal cycles go haywire and the planet itself shivers into a bone-wrenching fever. Many people find themselves bereft, astonished by the callousness of their own species and by the strange inability of modern civilization to correct its dire course. For those who recognize the animate earth as the source of all sustenance, a future once anticipated with excitement now looms as an inchoate shadow stirring only a vague dread. The disquiet that troubles their sleep stems less from a clear premonition than from the lack of clear images, from the difficulty of glimpsing any way toward a livable world from the place where we are now, at the end — it would seem — of a particular dream of progress.

Where are the fresh ideas, the new forms of perception, the new modes of association that might open us toward a viable future? Yet perhaps the quest for new ideas and new insights — the steady yearning for the new —holds us within the same dream of progress that’s brought the whole of the biosphere to this uncanny impasse. Instead of always looking off toward the future, perhaps we should strive to become more deeply awake to the full depth of the present moment that surrounds us, opening our eyes and ears to notice the countless other-than-human shapes of sentience that were obscured by the sense-deadening assumptions undergirding the modern era: assumptions regarding the inertness of matter and the mechanical character of material reality, its amenability to being analyzed and figured out by a human mind, or intellect, that floats somehow apart from and above that reality, able to dissociate itself from the body and the bodily earth.

Further, a clear assessment of the current impasse, and the possibilities hidden within it, may best be served by a keen awareness of the many forms of human life that were shouldered aside by the march of progress — ways of life we thought were left behind but that still linger (and even flourish) in pockets on the edge of this surging civilization.

The characters in Hill inhabit just such a time out of time. High in the foothills of the French Alps, in the shadow of Mount Lure, the inhabitants of a tiny hamlet eke out a tenuous living from a land dense with forests of pine and oak and juniper, thick with rock outcroppings and brambles and the scent of wildflowers (clematis, wormwood, honeysuckle) but also a few small orchards and olive groves, carefully tended. When, in what era? Well, sometime after the invention of the steam-powered threshers working the farms on the plain far below, and the advent of the distant railroad, and yet a long while before the arrival of the automobile: The journey up from the plain takes a full three hours by horse and cart.

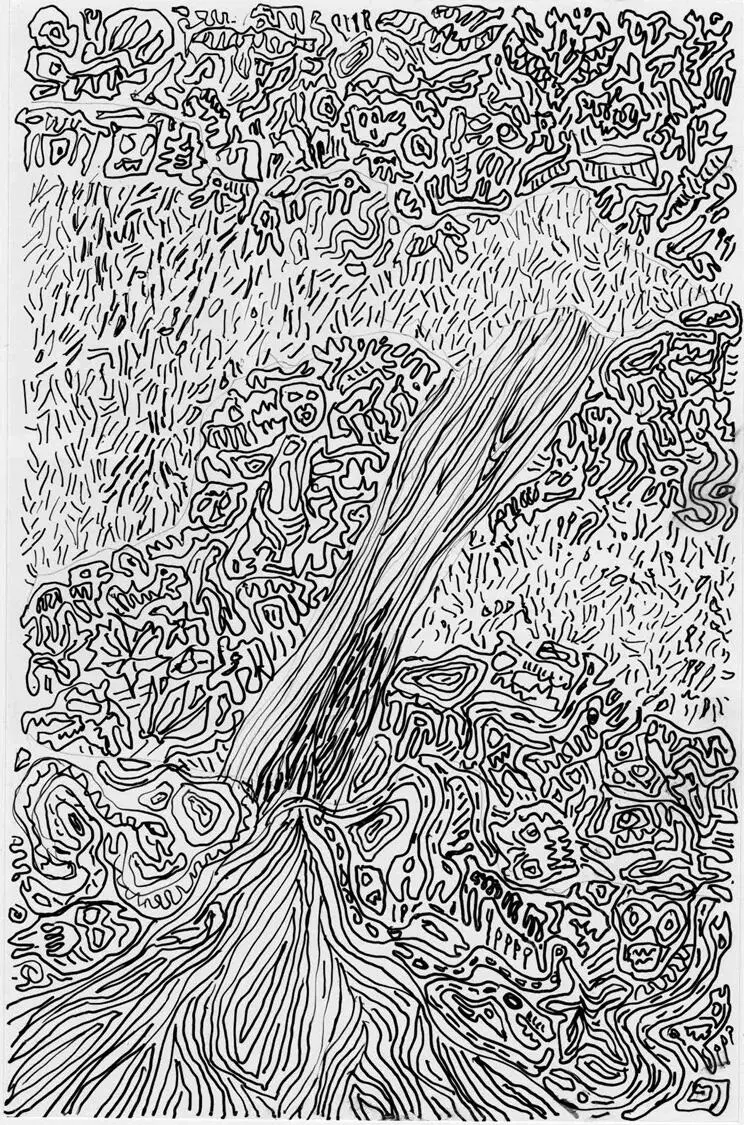

These peasants raise a few goats for cheese, and the menfolk hunt whatever they can that’s good to eat. Gondran and his wife, Marguerite, Jaume with his drooping mustache and his daughter, Ulalie, the simpleton Gagou and the garrulous but inscrutable elder, Janet — if one said that these were the main characters in the novel, one would not be entirely wrong. But neither would one really be right. For in this work, as in the other early novels of Jean Giono, the primary actors are the elemental powers of the more-than-human earth that enable and necessarily influence all the human happenings. The wind gliding up from the valley and spilling down from the mountain passes is itself a character, as are the flocks of birds who ride the wind’s moods, carving their way through its calms and its turbulence, and the forest with its trees heaving and flexing as underground roots feel their way toward fresh moisture. Up above, needles and leaves slowly bask and imbibe the sun’s radiance. The shining sun, too, has its exuberant life: “In a single leap the sun clears the crest of the horizon. It enters the sky like a wrestler, atop its undulating arms of fire.”

Shaping the tale as well are the creatures who slither and hum and bound within these wooded hills: the wild boar nuzzling among the stones for tubers, swarming insects, snakes coiled in the shade, a feral cat, lizards, hares — all the many sentient lives whose earnest engagements sometimes intersect our human activities at oblique angles (intersections that often go unnoticed, yet now and then catalyze unexpected changes in the habits of a person or the equilibrium of a community). The waters, too, are alive, not just the streams that sometimes swell with fresh rain but also those subterranean flows coursing through interstices in the geological strata, bubbling out of the ground as fresh springs or gushing up through an iron pipe into a carefully crafted fountain. For built things, as well, have their agency — are they not fashioned, after all, from materials birthed by the breathing earth? These whitewashed houses, for example, whose stone walls impart a sense of safety to those who dwell within them — don’t these buildings have their own moods and expressions?

Young Maurras half opens the door of his stable. He looks at the houses one after the other. They’re still sleeping, soundlessly, like tired-out animals. Gondran’s place alone is making a soft, rattling sound, behind its hedge…. The house has its eyes open — big, watery eyes, which Marguerite’s plump shadow passes across like a rolling pupil. The doorway drools a stream of dishwater.

Yet beneath the parched soils, underneath all these many lives, stirs the voluminous life of the hill itself — the brooding body that sustains, supports, and perhaps feels all that happens upon its surface. And this hill is but a fold in the broad flesh of Mount Lure, the implacable power spreading its shadowed wings, every evening, over this tiny cluster of houses.

Читать дальше