1913

VENICE HAD BECOME the most glittering city in Europe, a sort of summer extension of the Ballets Russes; each of them had their origins in the East. Diaghilev allowed himself to be followed around here by his favourites, and his favourites hung around here, ever ready to extricate him from financial situations that were so desperate that at eight o’clock in the evening he was never sure that he would be able to see the curtain rise at his shows, one hour later. How often have I heard his rich female admirers get up from the table: “Serge is on the phone; there won’t be any performance this evening, nobody has been paid.” In London, at Cavendish Square, I saw the conductor Beecham, the future Sir Thomas, dashing off to see Sir Joseph, his father, to bring back some money; Emerald got away with a bit of a fright.

La Pavlova opened a ballet school; Grand-Duke Michael entertained on Sundays at Kenwood, Oxford educated the youth of Russia, from Youssoupoff to Obolensky.

1913

I NO LONGER BREATHED the air of Venice except through intermediaries.

That October, I watched the girls I went out with in London returning to England, thrilled to have been able to get close to Nijinsky or Fokine in St Mark’s Square; already they were calling them by their first names. They brought back rich spoils, having stripped Venice, that great highway-woman, emptied the Merceria of its last lengths of velvet adorned with golden pomegranates, its green lacquer cabinets, and its glassware. I still think of them as young girls, forgetting that my companions are, or will be, in their eighties: one of them has died from a life of dissipation, too fragile for the alcoholic lures of surrealism and for handsome Blacks; she was the purest of creatures, the most damaged by life; another, the most beautiful, has experienced everything, the triumphs of stage and society, the thrills of historic moments, the most prominent of embassies; Time seems unable to wear down the marble of this statue…; a third lived a long and spectacular life, before falling into the inkwell, where she is still writing her memoirs; the fourth, the poorest of them, seeing that her youth was coming to an end, spent her last guinea on hiring an evening dress for the night; at the party, she would make the acquaintance of a South African magnate, who married her and made her happy.

1914

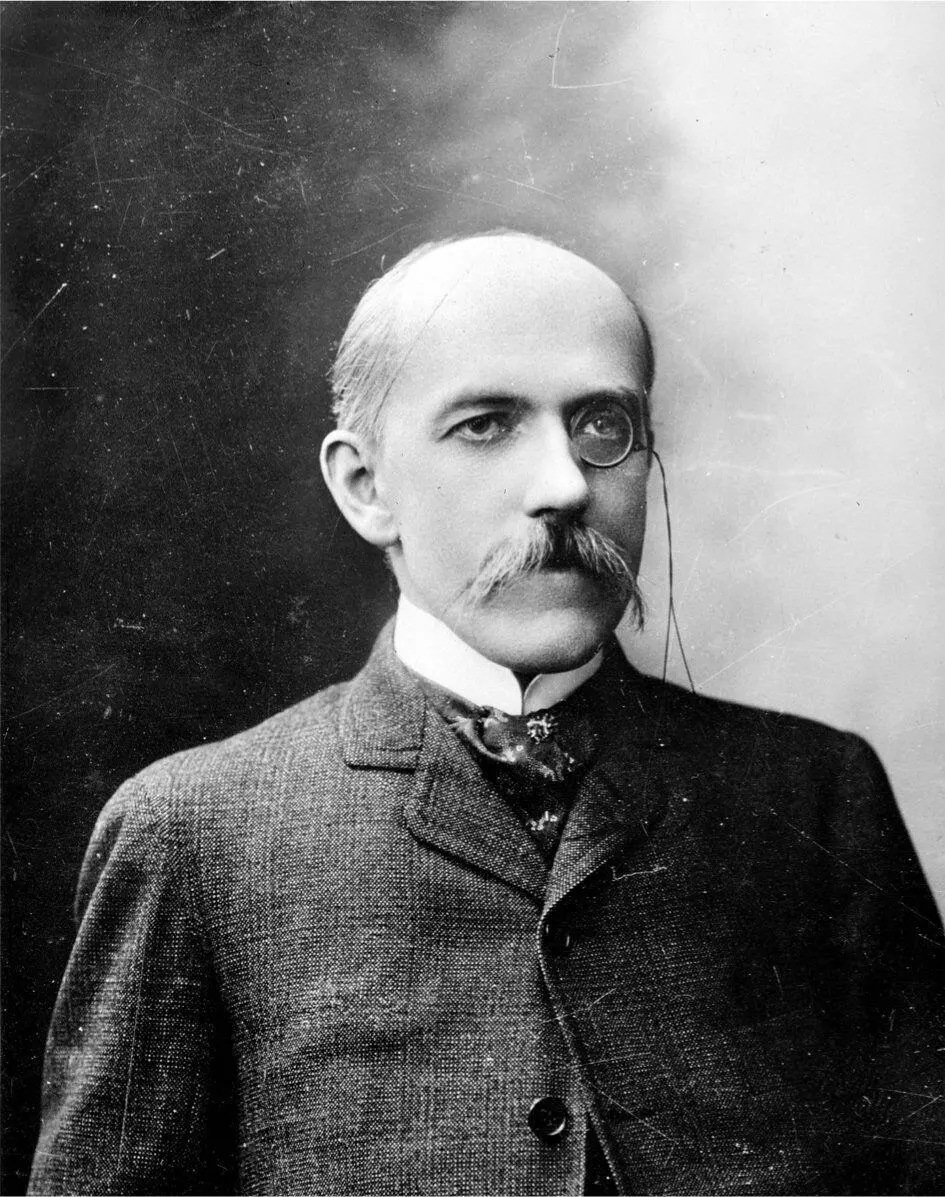

IN VENICE, the little French circle I had known in my youth had become a literary coterie. “Here comes the Muhlfeld salon,” they used to say in St Mark’s Square upon spotting Henri de Régnier. I possess many books of his that were inscribed to my father, I was mad about his La Cité des eaux and I lapped up his Esquisses vénitiennes , never expecting that a few years later Henri de Régnier would submit my first story to the Mercure de France . He stayed at the Palazzo Dario, the home of a Frenchwoman; behind his proud profile would appear Edmond Jaloux, Vaudoyer, Charles du Bos, Abel Bonnard, Émile Henriot, the brothers Julien and Fernand Ochsé, who had transported their mother’s coffin (Cocteau confirmed this) into their Second Empire dining-room at Neuilly. To me they all looked alike; you could imagine them dancing a farandole on some hump-backed rialto, made of tarred wood, such as the one in the Miracle of the True Cross , a bridge linking Paris to Venice, leading them from the Fenice to the new Théâtre des Champs-Élysees, which had been opened by Astruc the day before. Excepting myself, I used to call them the LONG MOUSTACHES; moustaches from which with the help of a magnifying glass you might have plucked a few tufts of Vercingétorix’s hair, some of Barbey d’Aurevilly’s whiskers, two or three hairs belonging to Flaubert’s BOYS, and last of all, one snatched from the Lion of St Mark’s Square. For these sensitive souls, Venice was their Mecca. Jaloux brought along his Marseilles accent, Marsan his cigars, Miomandre his talent as a dancer, Henri Gonse his rough and ready knowledge, and Henri de Régnier his look of a poplar tree that has shed its leaves in autumn; a delightful man, whose sense of humour maintained a close watch over his love life, the curves of his body ran counter to one another in a backwash of counter-curves, rather like the gilt wood or stucco of a piece of Venetian rococo.

Henri de Régnier

They all rallied to the celebrated war-cry of their master Henri de Régnier: “ Vivre avilit ” (Living debases), pursuing a Walpolesque, Byronic or Beckfordian dream; they were like disillusioned Princes de Ligne, austerely gentle, full of witty sayings in the manner of Rivarol,23 easily bored, quick to anger, chivalrous, and irritated by everything which life had denied them; they would gather at Florian’s, in front of a glass-framed painting, “beneath the Chinese one” as they used to say; they collected “bibelots”, a word that no longer has any meaning nowadays, lacquer writing cases, engraved mirrors or jasper walking-canes.

They passed around the best addresses among one another: those for point de Venise laceware, for chasubles and stoles; Jaloux would spend his literary prize money at these places; the only wealthy one among them, Gonse, bought himself a wardrobe that was supposed to have belonged to Cardinal Dubois; in order not to melt the lacquer, Gonse never lit a fire in his studio on the Plaine Monceau, but sat in his pelisse, blowing on his fingers to keep warm.

The older ones among them dressed in black; only Jean-Louis Vaudoyer dared wear English cloth.

They knew their Venice like the back of their hands:

“I still remember St Mark’s Square when it had its campanile,” Régnier explained; “do you know that at nine fifty-five, when the building fell down, my gondolier came out with this admirable remark: ‘This campanile disintegrated without killing anybody; it collapsed like a man of honour, è stato galantuomo .’”

“And what is more honourable still,” added Vaudoyer, “is that it collapsed on the 14th of July, as a tribute to the Bastille.”

The English have perhaps never loved Florence, nor the Germans Rome, as much as those Frenchmen loved Venice; if Proust dreamed Venice, they lived and relived her, in her glory as well as in her decadence.

“At the Palazzo Grimani…” Gilbert de Voisins, Taglioni’s grandson, began.

“Sorry… Specify your surroundings, my friend; to which Palazzo Grimani do you refer, there are eleven; the one in Santo Polo?”

“Or the one at San Tonia?”

“… Is it the one at Santa Lucca?”

“… Or the one at Santa Maria Formosa?”

“Or do you mean the Palazzo Grimani that’s known as ‘della Vida’?”

At the time of day when they met for their mysterious “ ponche à l’alkermès ”,24 the ritual drink that is mentioned on every page of Heures or L’Altana , these fanatical pilgrims would consult one another, their renowned moustaches yellowing from the smoke of their Virginia cigars. Where would they dine? At which osteria (that was the word they used)?

“At the Capello Nero…”

“At the Trovatore…”

“At the Bonvecchiati.”

“At the taverna at the Fenice?”

“At Colombo’s, in the Goldoni district?”

“Bottegone’s, in Calle Vallaresso?”

They had not been Rimbauds; none of them would ever be a Gide, whom they loathed, nor a Giraudoux, whom they preferred, nor Proust, whom they scarcely knew.25 Gide, Giraudoux and Proust had also worn their moustaches long; from now on they would shave them off, or trim them.

These were very charming men, who had little self-confidence, they were embittered and sweet-natured dandies, easily amused or driven to despair, who made fun of inverts such as Thomas Mann’s hero, that Herr von Aschenbach who was bothered by the naked shoulder that a young man bathing at the Lido had dared to reveal beneath his bathrobe!

Читать дальше