Christopher Hebert

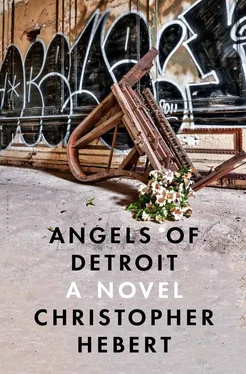

Angels of Detroit

Speramus meliora; resurget cineribus

(We hope for better things; it shall arise from the ashes)

Motto, official seal of the city of Detroit, adopted 1827

The car was a late-model Oldsmobile, the interior dank and musty, and the driver bore the distinctly sweet, rotting smell of overripe bananas. Lucius was his name. Thick dark hair sprouted from his knuckles in wild tufts. They were in southeastern Kansas, heading east as Patsy Cline quavered through a pair of broken speakers.

Dobbs hadn’t slept in days. He couldn’t put a firm number to it. The days whipped by like telephone poles. He feared he was losing the ability to see anything head-on. It was as if he and everything around him existed on separate planes, veering toward one another but never quite touching.

The noise of the highway made it sound as though Patsy were singing in the heart of a tornado.

After a couple of hours, they reached Lucius’s southbound exit, and Dobbs got out, shouldering his bag, moving on by foot.

* * *

At a truck stop in Topeka, he ordered coffee. Perched atop a pearlescent stool, he watched the pot empty its brown dregs into his cup. He imagined the coarse grit in the grooves of his teeth, the caffeine percolating through his veins.

There were only two other customers, each in his own remote booth. It was the hour for solitary travelers. The griddle was at rest, reflecting shimmery streaks of carbonized grease. A waitress hobbled from table to table with a magazine of straws clutched under her elbow.

“Your hair,” she said when she got to him. “Is it really that red?”

Dobbs caught his reflection in the mirror behind the counter. The color did seem unusually bright, the curls loose and wild. But his skin had the pallor of egg white. He was like a diseased tree, directing every last nutrient to its remaining leaves.

Every few minutes a thin, aproned boy came by and dropped a stack of dishes in the bus tub beside the counter. The dishes landed with an explosive charge buried at the base of Dobbs’s skull. Through the wall of hazy windows, he watched for trucks pulling in. He waited.

Other rides came and went. The drivers began to slip Dobbs’s mind the instant they pulled over, the moment they ducked to meet his eye through the open passenger window.

One night he found himself shivering, curled in the back of a pickup truck, sheltered within some sort of camper. Beneath the blankets lay a bed of cold steel. His eyes fluttered closed. He couldn’t seem to stop them.

In his dream, Dobbs was underwater. From somewhere up above, the light trickled down, like something solid falling. His lungs were strong. Rather than surface, he swam deeper and deeper. There was someone following him he couldn’t seem to shake.

And then the water was gone. Dobbs was sitting at a table in a cavern carpeted with sand. Exhausted from his swim, the man who’d been chasing him lowered himself heavily into the opposite chair. He smiled. They were like old friends meeting for a beer. But the man’s face bore only the faintest outline of something vaguely familiar. He spoke of women he’d known. His tone was nostalgic. He gestured lazily with his hands.

In his own hand, Dobbs held a wooden pepper mill, tall and slender, the curves perfectly contoured to his fist. The man winked, as if to beg Dobbs’s indulgence. Dobbs winked back. And then he raised the pepper mill. And then with a lunge, he smashed it back down, cracking the grinder against the man’s temple. Under the blow, the man swayed backward, but it was as though he were merely stretching. He sighed.

Dobbs struck him a second time, a third, a fourth. The blows left not a drop of blood, not a scratch, not a bruise. The man displayed no hard feelings, no discomfort, no indication of thinking things should be any different than they were.

Dobbs awoke with a shudder. The truck was slowing. They came to a stop on something loose and gravelly. Shards of light knifed through the door. Dobbs felt as though he were back underwater. But this time his lungs were spent.

He groped for a knob, a handle. There seemed to be no way out. Kicking aside the nest of blankets, he used his shoulder as a ram, but the wooden door of the camper absorbed him with indifference. Dobbs edged back and tried with his foot. But it was as if the light were pushing back.

Someone on the other side was yelling at him, but the cars slashing by warped the words. The lights formed blue and white and red spots on his eyelids.

Dobbs sat in the back of the cruiser as the cop fiddled with his computer, putting the finishing touches on the speeding ticket.

Up ahead, the truck and its makeshift camper pulled away from the shoulder of the highway, leaving him behind. Dobbs thought he felt something inside himself pull away with it.

On the other side of the partition, the cop cleared his throat.

Why don’t you have an ID? he wanted to know.

I don’t drive, Dobbs said.

Where are you coming from?

Phoenix.

What were you doing there?

A job.

Doing what?

It was temporary.

What was your address there?

I was only passing through.

A motel?

A house.

What was the address?

No one sent me any mail.

The cop had been looking down at the computer screen, occasionally keying something in as he talked. Now, for the first time, he lifted his face to look in the rearview mirror. His disembodied eyes hung there a moment, and Dobbs saw in them a weariness not unlike his own.

“Don’t you know hitchhiking is illegal?” the eyes said, raising one brow.

“I wasn’t hitching,” Dobbs said. “I was riding.”

“And you think it’s legal to be riding in the back of a pickup?”

“It is in Kansas.”

Which was true. And the cop knew it, too. Which was why he sighed.

These were the kinds of things a person had to keep track of. Walking the line required knowing exactly where the line was.

And so they rode in silence until they reached the border, Missouri on the other side.

“You’re someone else’s problem now,” the cop said, pulling over at the bank of the Kansas River.

For the next hour or so, Dobbs loitered through a light rain at a gas station just outside Kansas City.

“I’m trying to get to Detroit,” he said, as each new car pulled up to the pump.

No one would admit to being headed in his direction.

Of the next several days, Dobbs remembered only a gray-eyed man in a camouflage hat, gnawing on a pipe stem, saying, “Why don’t you get some sleep? You look like you could use some sleep.”

And Dobbs saying, “I’m fine, fine.”

Then minutes or maybe hours later, Dobbs was aware of the driver emerging from a fog of smoke to lean across the passenger seat and open the door. In Dobbs’s mind, there was a sudden clearing, like a flock of crows exploding from a treetop. He got out of the idling car, slowly testing the ground, one foot at a time. The car skipped away from the curb.

Dobbs was standing in front of the bus terminal. The sign at the gate said WELCOME TO DETROIT! The exclamation point was twice the size of the letters, as if whoever put it there were anticipating skepticism.

Dobbs didn’t remember having asked to be dropped off here. It was a strange choice. Had the driver thought the first thing he’d want to do as soon as he arrived was turn around and leave?

It was morning, early. The sky bleary. Dobbs was standing on a one-way street, but he turned to look in both directions. There were no other cars, no buses in the parking lot. There was no one out here but him. Down an embankment to his left ran the highway, but even it was mostly quiet.

Читать дальше