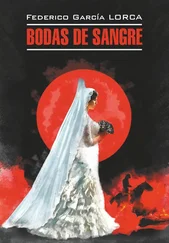

“Here, in this very place, I spoke some years ago about that poor gentleman, God rest his soul, with an Englishman or an Irishman who picked up everything I said, in secret and without my knowing it, on one of those things, what do you call them?” Ruiz Alonso stammered.

“A tape recorder,” the man with the cut on his face suggested.

“That’s it, a tape recorder. Then he published it in a book about the death of that poor unfortunate, may he rest in peace. Can you imagine the lack of principles?”

The man with the scar did not venture a comment. He limited himself to tracing in his notebook two parallel, very short lines, which he then crossed with another vertical, drawing a kind of Cross of Lorraine.

“I don’t have any tape recorder,” he said as if he were talking to himself.

“I don’t doubt it. I don’t doubt it.” His emphasis betrayed Ruiz Alonso’s hidden uncertainty. By then he already must have regretted agreeing to the interview. “You’re a gentleman.”

“There isn’t a single creature on earth capable of knowing who he is,” the man with the cut face replied, quoting Léon Bloy.

“It’s possible. It’s possible, though I don’t really understand these things. I’m only a poor retired typesetter.” He hesitated a moment, as an actor would who gauged his audience before uttering an obscenity in the middle of a mystery play or a classical tragedy. “I’m a son of the people.”

“Excuse me, what did you say?”

“I said I’m a son of the people.”

“Son of the people or not, you will pass into history, Señor Ruiz Alonso. Or, to be honest, you’ve already entered it, because once a poet was murdered whom you had arrested,” the man with the sliced face replied, with no irony.

“I didn’t arrest him. I was ordered to arrest him, God keep him in His glory, poor thing! Yes, I was ordered to arrest him and I had to obey because we were at war, when all orders are sacred. I swear by the Blessed Virgin!”

“Is this the truth?”

“This is the beginning of the truth,” he specified after thinking about his answer. “The governor of Granada was visiting the front that day. An officer whose name I forget because with age even the most terrible memories become confused and grow dim, gave me unavoidable orders. ‘Look,’ he told me, ‘this gentleman has to appear in the offices of the Civilian Government because that’s what the governor has ordered. He wants to find him here when he returns from the front, with no delays and no excuses. He’s very interested in talking to him and wants him brought in duly protected: no one touches a hair on his head. For this service he has thought of a person with authority and prestige, like you, Ruiz Alonso.”’

He spoke in a very quiet voice, almost in whispers that the man with the scar sometimes made note of beneath the Cross of Lorraine. He said the most terrible memories became clouded but seemed eager to please as undoubtedly he hadn’t been when he was sent to arrest me, assuming everything had happened in the way he said. The yellow dribble had dried at the corner of his mouth and his hand trembled when he persisted in wiping it away with his palm.

“I was familiar with that version of the orders you say are sacred in wartime.” Again he spoke with absolutely no irony, looking at the cups of cold coffee as if they were a still life by a master, while Ruiz Alonso nodded his head. “As you must understand, it’s impossible to believe.”

“Yes, yes, I understand that too. But that’s how things were back then. We were at war, an all-out war to the death, don’t forget that. I can swear to you by all the saints in heaven that this is the truth of the matter.” He stammered now and was ashen, as if he had reached the end of his strength. Suddenly he flared up, hitting the table with his fist. An unexpected rage brought him back to life. “Then all kinds of atrocities were told to slander me. They’re so absurd that I laugh, yes, I laugh, when I think of them.”

“What do you laugh at, Señor Ruiz Alonso?”

“Let’s do one thing at a time and put things in some order! Yes, in some order, eh? All right, well look, to begin with, that gentleman, may he rest in peace, was a degenerate. When I say it like that, with my usual frankness, I don’t intend to insult his honorable memory, because everybody knows and talks about it. Look, I’m a man from another time. A time that today seems very distant to me, in light of so much pornography and crime. Well, with my sense of morality and my religious piety, I say that his aberration doesn’t matter to me at all because it’s part of his private life. Yes, sir, his private life … ”

“And with his death, even more private.”

Ruiz Alonso stopped speaking to look at him indecisively. Suspicious and vulnerable, he seemed fearful of missing any sarcasm at his expense. Then, unexpectedly, blinking as if dazzled, he thought he understood. His eyelashes were growing in white, and a labyrinth of small veins flared on his pale cheeks.

“Yes, yes, I understand. Death is as private as life, because no one can live or die for another person. You can’t for me, and I can’t for you.”

“Or you for that man.”

“What man are you talking about?”

“The one you arrested or were ordered to arrest.”

“Ah, yes, may God have pardoned him! I pray for him every Sunday at Mass, though they wanted to crucify me alive. I was getting to that, but I lost the thread and forgot what I was saying! I said I didn’t care whether that gentleman was queer or not, if you’ll excuse my plain speaking, because more than anything else I respect the privacy and dignity of a human life, follow? The disgraceful thing, the unspeakable thing, is what they did to me.”

“What did they do to you, Señor Ruiz Alonso?”

“Defamed me. Yes, sir, defamed me in writing and in printed books. That Englishman or Irishman, the one who secretly picked up everything I said on a … What did you say it was called?”

“A tape recorder.”

“Yes, that’s it, on a tape recorder. Well, he told me a Frenchman had written a biography of that gentleman who was shot, may he be in glory! And it said, just as it sounds, that I arrested him because he caused jealousy and arguments among us homosexuals. I admit that when I heard an insult like that, I lost my temper, because each man has his honor and mine is double: being very Christian on one hand but also very much a man on the other. ‘You tell this French gentleman,’ I said in just these words, or others like them, ‘that if he doubts my virility he can bring me his mother, his wife, or his daughters, and though I’m an old man I’ll use them as they deserve, given their profession, which the police in their country have on file.’ I wasn’t boasting, I swear, because here where you see me, a decrepit old man, I still get a hard-on that’s a joy to see.”

The afternoon was dying over the Sierra on the stage in hell. The sky reddened like the mouth of a furnace. Then it moved to ocher and scarlet, like the onyx slipper snail in my last dream in Madrid. (“It’s called Crepidula onyx , which is its exact technical name in Latin. In the tropical Pacific, it’s known as the onyx slipper snail,” Dalí had told me in his accent of a Catalan comic. Then, with no transition: “Have you read Proust? No? Never? You still need to be educated, but with a little luck I’m going to smooth and varnish you until you begin to look like an authentic poet. As a child, before he was taken to the theater for the first time, Proust thought all the spectators were watching the same drama but remained isolated from one another. In other words, the way we read history or a voyeur shamefacedly spies through the keyhole.”) The lights went on in the Lyon and at that uncertain hour Ruiz Alonso’s shrill voice grew louder, proclaiming his attributes. Loving couples on sofas and old men engrossed in open newspapers suddenly looked at him, smiling.

Читать дальше