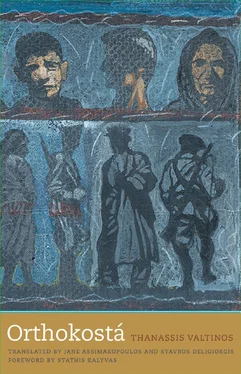

Speakers in the book are either warned, typically by another speaker, not to mention any names, or they suddenly turn silent with an expression that comes close to a gruff, but ambiguous “I’m done talking.” The concluding reference to much that is unspeakable in Valtinos often assumes the gravity of historical closure (“The rebel insurrection was over. . It was over for good,” the Greek verb in this context being a derivative of catharsis ). Occasionally the account progresses towards a note of exorcism. The parting shots of most of the recorded stories often end with a laconic one-liner (“that bloodshed still hounds him”). The beginnings, on the other hand, tend to be almost always teasers that, by dint of repetition, could as easily apply to the captive audience as to the speaker: “We were arrested when. .” Once the captivity narrative gets under way, however, the contents are surprising in their immediacy. Both captors and captives, in the hundreds, are ill-equipped for the mountainous terrain, both are chronically undernourished, few attempt to escape their pre-ordained ranks, and both stoically accept the long marches that serve to maintain a supply of men and women hostages to be culled for summary retaliatory executions whenever the captors are attacked.

The oft-intuited dilemma in Orthokostá , “damned if you do, damned if you don’t,” sounds painfully familiar from the ancient historians’ accounts of cities destroyed for not choosing neutrality and then destroyed, a second time, for having chosen it. Like all complex epics Orthokostá is rich in war paradoxes. Glaucus’s meeting with Diomedes in the sixth book of the Iliad manages to tinge the action of the entire poem with the possibility of somber ironies (“Go find yourself other Greeks to kill. .”) where one would least expect to find them. In one sense there is little that is peculiarly Peloponnesian in the list of the Orthokostá atrocities. The ancient lyricists such as Tyrtaeus and Callinus testify to the opposite. And so do Homer and Sophocles when it comes to orders that the executed not be buried. Were it not for the gods’ daily intervention Achilles’ punishment of the dead Hector’s body in the Iliad would have resulted in the same kind of posthumous disfigurement a man in Orthokostá suffers at the hands of his torturers. “Mémos’s Fields” refers to a spot named for a local official and torture victim who was shot during a march he could not keep up with because of the beatings he had received on the soles of his feet. As with the heroes of antiquity, place names are given to commemorate a victim’s tragic death. Walter Benjamin’s eighteenth thesis on the art of the storyteller — once again from his essay on Nikolai Leskov — sums up the etiological presentation as one that allows the “voice of nature” to speak, including the dark work of hatred. An anonymous initiative in itself, the naming of Mémos’s Fields does not monumentalize the circumstance of victimization, nor is it triumphalist. One corner of the countryside that had been repeatedly crisscrossed by forced marches of hundreds and hundreds of civilian “enemies of the people” now has a voice and a face.

Valtinos’s speakers come from or go through places that are inseparable from their own and their families’ identities. The metaphor, a synecdoche really, is saying, “If you’re looking for ‘art’ it’s out there,” in a territory of narrowly topical and date-bound, often warring, site-specific states. Allusions to places of birth, mixed in with the speakers’ relatives and acquaintances, make Orthokostá appear at first to be just another demographic dump of the Greek Civil War and its participants. To the untrained ear they are as superficially unattractive as the four-hundred-line catalogue of ships in the Iliad —a 1955 translation omitted them as of no interest to the modern reader! — which enumerates both the European and the Asian expeditionary contingents that participated in the siege of Troy. It is true that the illusionism of the main action in the Iliad is momentarily suspended. In its place, and behind the euphony of locations like Sparta, Epidaurus, Mycenae, Euboea, Ithaca — to Valtinos’s “Parnon” “Karatoula,” “Tripolis,” and “Argos”—one notices that Homer’s catalogue is also about the families the troops leave behind, the attributes of the locales they come from, the miniature epics of still other alliances and hatreds: in other words of countless other Troys embedded in the framework of the main epos. In Orthokostá whole neighborhoods, individual plots of land, and even stone fences are known by their founders’ or builders’ names. Trajectories of movement through fields or towns are marked by itemized ownerships. The naming rituals of older titles, the degrees of belonging to a family network, or the rituals of christening and mourning that fill the book all build up to the chora —a term adopted by the theoretician Jacques Derrida from Plato’s Timaeus for the matrix of villages that, in this case, mysteriously engender language and social relations. The unfailing rootedness to conditions on the ground of any entries in Valtinos’s lists, long or short, adduced by the narrators seems to be saying insistently that whoever touches a man touches a place, cherished or haunted.

Chora can be alarmingly literal as well. In one of the shortest chapters of the book the speaker describes a team of mules loaded with sacks of chestnuts traveling by night. When the animals suddenly freeze in their tracks the muleteer wonders whether they had sensed the macabre past under their hooves. Washington Irving and Balaam’s Ass from the book of Numbers converge upon the reader’s novelized interviewee, who wonders whether it was “the devil playing tricks, or. . the smell of blood — three years since Fotiás was killed there.” The reader has long sensed that the indirection by which so much information is conveyed to the page is intentional and that possibly the blurry contours and the discontinuous nature of its interludes are so many nudges toward the participatory cast of this fiction, the active connecting of lines of thought and the juxtaposing of the varying gradients of truthfulness (or posing) between the book’s two covers. The reader’s co-authoring of Orthokostá is of the same critical order as that called for by Laurence Sterne’s refracted fabulations in Tristram Shandy or by Julio Cortázar’s Escherian Hopscotch .

Valtinos does not divulge the information as to how the first-person reports in the novel came into his possession, or the process by which they lined themselves up for the readable, published version. The documents fascinate from the start by their alternating emphases and changing points of view. Some are prodding investigations while others are tableau-like miniatures of pathos. Even bathos. Take the execution of an emaciated old woman who refuses to betray her son’s whereabouts and is killed on the spot. Others read like Norse sagas. Burnt Njall is an apt analogue as the wind blows in cinders from burning homes in the vicinity. Homer’s retelling of the siege of Meleager’s home in the Iliad is clearly reenacted here. Meleager dies when his external soul, a log that was saved by his mother from the hearth when he was born, is thrown back into the fire by his mother. Orthokostá -like — paralleled by a notorious female rebel leader who stridently demands that her own father and brothers be put to death — Meleager and his household are doomed to die at the hands of none other than his mother’s brothers. The opposing sides in the novel burn each other’s homes down while also holding separate “courts” in the mountains to judge and hang their rivals. A sizable part of the population is made to choose between forced conscription and summary execution while another beleaguered group prefers volunteering for camps in Germany to being held hostage in the place of relatives who had taken refuge in Athens.

Читать дальше