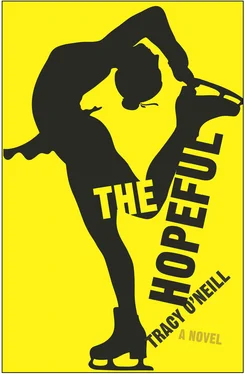

Tracy O'Neill - The Hopeful

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Tracy O'Neill - The Hopeful» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2015, Издательство: Ig Publishing, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Hopeful

- Автор:

- Издательство:Ig Publishing

- Жанр:

- Год:2015

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Hopeful: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Hopeful»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Hopeful — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Hopeful», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“Figure skating,” Mark said smiling, “is not much different than American politics.”

But figure skating was much fairer than American democracy, I thought. In rinks, the justice of corporeality trumped patriotism. At one point, I had been between Filthy Phil and The Russian. Lauren had been my coach for years, but sometimes I wanted that Salchow more than I wanted not to hurt her. Filthy Phil got his name from his five o’clock shadow and the way he touched his girls’ butts. All the coaches touched their students’ butts; it was the only way to make us feel how our bodies should be positioned for certain skating movements. They grabbed and pulled our pelvises forward. They called this being beneath ourselves, and being beneath ourselves was the only way to turn correctly in the air. But parents said that for Filthy Phil, butts weren’t just business. That left the Russian. “Better dead than red to some, but he does get results,” my father had said. “The judges couldn’t argue with the Salchow.”

“So you went with The Russian?” Mark asked.

“No,” I said. In the end I stayed with Lauren, maybe because I loved her. She had drilled me until I landed double loops, scratched out odd-bodied spins. There was genius to her methods, the innovations that flipped pain into the appearance of ease. I remembered when I was breaking in new skates, my feet bloody-pus blistered, and how she sent me running barefoot on a trail of broken seashells in the parking lot. “You want to know pain?” she called. “Pain is not cutting it. Pain is falling short. Pain is not making it. Are you in pain, Ali? Are you in pain?” I pounded over the seashells — no no no, no no no pain — until nothing could hurt me except the things I thought, the mistakes all my doing, like the one that broke my back and made me a normal girl, wallowing through summer tutoring.

“Tell me more,” Mark said, and I did, though for him it was just a blip in the Cold War. For me, it was the only thing worth fighting for.

A few weeks after I began my tutoring sessions with Mark, I didn’t need to immobilize anymore. The physical therapist prescribed abdominal exercises for my recovery, and I enjoyed the sit-ups, even if their only objective was that I could function regularly. It was nice to be behind — it meant there was somewhere left to go, even if that somewhere was, as my father once said, all the way up to mediocre. It was a better way to exhaust my moroseness than imagining windmill sails slicing synapses between sadness and the everyday.

“This is excessive therapy,” my mother told me one afternoon. I’d been at it on the floor, pulling rubber cords colored like primary school crayons and rolling my spine against an oversized Styrofoam log. “There are reps and sets for a reason. There’s the expression ‘too much of a good thing’ for a reason.”

But there was this or there was waiting to find out if a new love would appear. It was this or believing that my life would be like those arranged marriages where the only thing to do is pray that love will be slowly cultivated. “Rep is short for repetition,” I said.

“How many reps has it been today? Don’t lie to me, Ali.” Her hands were on her hips.

“Reps enough for fighting form,” I said. “I’ve lost a lot of upper body muscle, but my quads are still good and strong. I’m more concerned about how the weight gain will affect my skating.”

“What are you talking about?” she said. Against the backlighting of the door, my mother’s face seemed to slip away and reassemble itself beneath the shadow of her perfectly teased thicket of hair. “Ali, listen to me: you will never be able to skate again.”

A zip of heat clipped up my neck. Never was a word I couldn’t conceive of, negative infinity, no for forever, always the end, nothing ever, never, death.

“If I can walk, I can skate.”

“You know that’s not true,” she said quietly. “I’m sorry Ali.”

“If you believe, you will achieve!” I said, the lame desperation rising in a squeal.

“You could skate laps once in a while. That could be fun. But you’re never going to compete again. You fractured two vertebrae.”

“And the fractures have healed— that’s why I’m allowed to do therapy now.”

“This time it’s fractures. The next time, you’re paralyzed. And we both know that this isn’t weight gain , Ali. You’re a woman now.” She smiled in a way that I guess was intended to be encouraging, a Merry Christmas twinkle tone floating that awful word: woman. “Nature has finally caught up to you. It’s a good thing. The way you were before isn’t what’s supposed to happen at your age. I was a fully developed woman at fourteen. You were exercising too much. It kept what was supposed to happen from happening: puberty.”

“Puberty was never supposed to happen,” I said. I looked down at myself, this body, average by the standards of average people, thick and useless to the rigors of figure skating. Thickening thighs and swelling chest, rounded stomach and those other hanging female things— that these were meant to take over my life sickened me.

“It’s an inevitable and beautiful part of life,” she said. “It’s how the body makes creating life possible.”

“ I created life with my body,” I said. “You know nothing about creating life.” It was the worst I could say to her, and for a moment she didn’t speak. It had been her choice to adopt me, but maybe it wouldn’t have been if she’d had the choice of a successful pregnancy.

“It’s a good thing I love you because I certainly don’t like you,” she said. “If you weren’t my child…” She didn’t finish, and it wasn’t difficult for either of us to imagine me as not her own at that moment.

I gathered my Styrofoam and tubes and ran upstairs. The conversation was over, but skating was not.

I’d forgotten Mark was coming for a tutoring session that day until he knocked on my bedroom door. From my stereo, drums were rumbling and when he came in, Mark pretended to work the mallets with his thin, strong arms, beat the timpani, titillate the triangle.

“Air drums? A virtuoso,” I said.

“You and me both: a virtuoso duo,” he said. “What are you listening to?”

I explained that this clash boom bang was the music to which Sam Esser had once choreographed my short program. Esser, whose biceps were as legendary as his choreography, had changed my life. He’d been a pair skater in the nineties with Fiona Tile, a girl thought too big for to be lifted and thrown. Everyone called it charity until they won the national championship. Tile retired the year after they won to beat a marred record to the punch. “This whole sport is a banana peel waiting to turn you into Charlie Chaplin,” she had said. “Quit while you’re winning and you’ll never quit being a winner.” Sam began choreographing at SCOB, and my father commissioned him the year after I won regionals. All my previous music had had stories implied, ballets and operas and movie soundtracks, immortals and forests and the triumph of magic. For this routine, Sam said, a story needed to be formed. If you don’t want to tell a story, he was known to say, then be a gymnast. In skating, story was the motivation for every inflection of the arm or back.

“Like this?” Mark chopped his arms, then rounded them over his head and turned in a circle.

“I can tell you’ve done this before.”

“How about this move?” He beat his chest then curled himself in a fetal position, rolling on the floor and kicking his legs. It was the part of the song where Sam had instructed me to listen to what the instrumentation was doing: not getting anywhere, just spinning in cycles. This, he said, was why I needed to portray what happens when life begins to feel accidental. At the time, I couldn’t understand what he meant. I understood my days as part of a meritocracy. I starved achievement out of myself. I invested bruises into the future.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Hopeful»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Hopeful» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Hopeful» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.