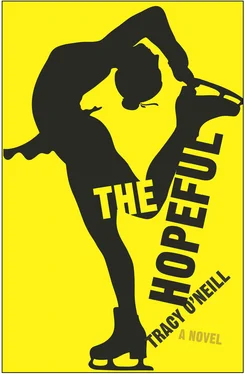

Tracy O'Neill - The Hopeful

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Tracy O'Neill - The Hopeful» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2015, Издательство: Ig Publishing, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Hopeful

- Автор:

- Издательство:Ig Publishing

- Жанр:

- Год:2015

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Hopeful: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Hopeful»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Hopeful — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Hopeful», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

I laugh. I could like the doctor if she wasn’t my doctor.

Multiplicity I’ve never suffered, except of course, of mothers.

Yet we know that you did not only have a biological mother and an adoptive mother but also a biological father and an adoptive father. Why do you think it is that you mentioned only a multiplicity of mothers?

She asks a good math question, though it’s not a balanced equation. The shortest distance between two points is a straight line, but the only mathematical fact I know is that families are always multiplying and dividing, adding, subtracting.

It must be quite trying for you, Doctor, to do this over and over, I say.

Perhaps you’re projecting? Perhaps it is you who finds it trying to go over what has already happened? Or perhaps it is you who finds it trying to uncover the inconsistencies in your account.

Of course I do! It’s trying, I’m trying. I don’t know the answers.

Well just think it over then. Why do you speak of a multiplicity of mothers and not fathers?

I think of this multiplicity, how once I hadn’t known what it meant to be adopted, that it meant to be unburdened and reburdened. I didn’t have you inside of me. You had another mother who she couldn’t take care of you, but I could , my mother told me. Maybe she was too young or didn’t have a job. I noted that she didn’t have a job either. I don’t have a job because I have you , my mother said. Then, I don’t know, Ali. I don’t know why she couldn’t. Maybe she wouldn’t. Maybe she didn’t want to have a child. Probably she’s dead.

Let me ask you a question to answer yours. Why do you do this of all things, Doctor? Why is this your life? You have Patient X, and you talk and you talk — problems, the past, problems of the past — and then finally, the breakthrough moment. But then what? Patient X sees the problem. She sees the deep-rooted cause of all the misery. But how does she change it? The deep-rooted cause of misery is still there because it’s located in the past. So why do what you do?

Treatment is not simply about diagnosing the “deep-rooted cause,” as you refer to it, though much of it is about understanding causal relationships. It’s also about developing a plan for future action. But we needn’t speak in generalities. We’re here for you. What would you like to see result from these sessions?

I didn’t choose to come here, Doctor, so why would you presume I have any end goal in sight?

None of us choose to “come here,” as it were. But still we create objectives, we enact plans, we succeed or fail. It can be anything. As I said, we’re here for you.

I’m sick of me, Doctor. I am the disease.

You are not a disease, but who is it you think you are infecting?

My parents, of course.

Most believe it’s something of the opposite that’s true, that their parents have ruined them.

But most descend genetically from their parents. I descended upon them.

And yet you descended from their nurture if not their nature.

Their nurture!

We’re quiet for a minute. She looks at me and I look at her, these mirror images, doctor and patient. There’s nothing of the child’s staring contest in it. No one is going to break down laughing.

I think it’s interesting that when I asked you to start from the beginning of your story that you began with your skating life, she says finally.

That was the beginning of my life.

You must have had a life before skating.

That’s not where I began my life, I say. The words come out fast, as though I’m not even the one saying them, as though the voice and sentiment precedes me.

It seems you don’t want to talk about your life before skating, so why don’t we talk about what happened after? After your spinal injury.

And I can see that she’s giving me two options. She wants me to believe I still have choices.

The summer after the accident, I turned into someone who didn’t resemble a younger version of my mother. One day I was sharp as a blade. The next there was gore in my pants that meant I was a woman. What I saw in the mirror could not swindle physics but was a swindled physique. It suggested an hourglass of slipping sand. My mother’s concerns were about the development of my mind, not my body, however, so she hired a tutor for me, worrying that years of homeschooling had left me behind my peers. His name was Mark Orrechio, and he was twenty-four years old and taking time off from his doctorate program to campaign for a third-party politician most voters didn’t know existed, a little big-voiced communist named Leonard Leonards who had famously thrown himself in front of a bulldozer to protect an independent bookstore as the former bookstore owner yelled, “Stop hamming it up!” (She had sold the store to a chain and was moving the next day to a gated community for people who didn’t work anymore.) They showed this film clip on the news when Leonards announced his candidacy with a speech titled “A Piece of the American Pie for All.” Evidently, this speech had excited Mark, and my mother got a lucky deal on an almost Ph.D.

The day we met, my mother brought him up to my room before she left for the salon. I was still in bed, steaming beneath the covers, and even when I saw two pale green eyes lighting across me, even when I realized this was the first man to come into my room that wasn’t my father, I stayed in the sulk of my sweaty linens.

“Lying is no way to live,” my mother said. She figured company would embarrass me vertical or at least into mascara. I was wearing leggings, my unbrushed hair twizzled into dark filigree. My only excuse for the degradation of my hygiene was that I was down one identity, and there was no longer anyone left I wanted to try to be.

“I can’t bend at the hips,” I said. “How will I sit?” I pointed to my torso where under a T-shirt I wore a medical corset to form my spine properly. Cruelly called an immobilizer, it pitched me erect, and because it extended over the tops of my thighs, I couldn’t sit. Nor could I walk so much as waddle side to side like a metronome, my torso swinging in the sweat-drenched synthetics.

“If sitting was a Salchow, you’d find a way,” my mother said.

“If sitting was a Salchow, I definitely wouldn’t be able to do it,” I said. “I just want to finish my coffee in bed.”

Mark rushed into the conversation. “Coffee is how I got through grad school.” He didn’t speak so much as blurt, and immediately I liked his awkward valor.

“Coffee is how I got through starving,” I returned. To be afraid or to laugh? he looked to wonder. “To getting through,” I said, and he raised his paper cup as though we were celebrating.

“To getting through.”

My mother departed quickly—“I’d better be leaving for my permanent then”—and I knew I’d embarrassed her. Replacing my coffee cup on the bedside table, I watched her wilting curls shrink in the doorway.

Mark took his hand in and out of his pockets, then sat at the end of my bed.

“I’m Mark,” he said. He held one hand above my body.

“I’m pathetic,” I said.

“And self-effacing,” he said. “A virtuoso.” When he smiled his cheeks wrinkled like disturbed pond water.

He started talking about himself, about graduate school, about not being in graduate school, about Leonard Leonards, about communism. All I knew of communism, I told Mark, were unfair advantages. Until the Soviet Union dissolved, communist countries churned out some of the best skaters in the world, while only moneyed families could afford the expense of figure skating in the United States. Soviet skaters were fed caviar, trained, and professionally massaged with government funding. The Eastern Bloc had had an advantage, and even now for an American to take lessons from a former Soviet was somewhere between chic and treacherous.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Hopeful»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Hopeful» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Hopeful» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.