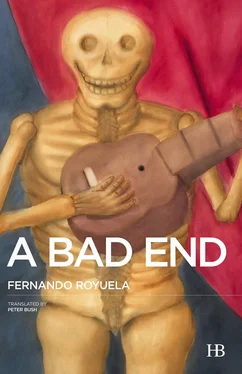

Fernando Royuela - A Bad End

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Fernando Royuela - A Bad End» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2016, Издательство: Hispabooks, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:A Bad End

- Автор:

- Издательство:Hispabooks

- Жанр:

- Год:2016

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A Bad End: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «A Bad End»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

A Bad End — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «A Bad End», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

I was born a dwarf, as you see me now, my legs tucked under my body, my arms that barely reach my hands, and my hands squeezed against my shoulders like little wings with fingers. I was born a dwarf, but a human being is not measured by size or by degree of beauty, but by the quantity of cash he handles; the greater the amount of cash, the bigger the size, naturally. There are no dwarves when money is at stake. I was born a dwarf, but it could have been even worse, because I could have been born a pig to be slaughtered or even a worm used for bait, one that dies half on the hook and half in the fish’s mouth. Things are what they are, and little or nothing can be done to go against their nature. Only the very brave are occasionally courageous enough to defy their destiny. The mad sometimes try, but their attempts have no merit.

Even toothless, little Santomás was radiant with joy on that Sunday morning when he was preparing for his first communion. His grandmother had been to Valencia to buy him a sailor’s suit with blue braids and a lanyard of cord plaited from gold thread that snaked across his chest and slipped into his jacket pocket in appropriate military style. He was toothless. I couldn’t take first communion and never even acceded to the grace of baptism; in terms of Roman Catholic orthodoxy, when I died, I would go to hell. Pitiful beliefs.

Little Santomás was one of those stuck-up bastards that rejoice in an unctuous blind faith in themselves, yet I expect it’s for that reason he experienced a death lit up by flames. The children were so looking forward to receiving the communion wafer that May Sunday, and, in comparison, I’d have been happy, too, if Don Vicente hadn’t gone and refused me the sacrament. I shouldn’t have bothered to tell him what I wanted, I should have anticipated his contempt, but only Providence is prescient, and sometimes our ears are deaf.

A bright sun shone that day, a pure kind of sun, the sort that fills men with hope. In the front pews, in their Sunday best, the children were anxiously waiting for the ceremony to begin. They exchanged sly smiles that spoke of the happiness in their hearts. The packed church was heaving. Coughs, clearing of throats, sweat galore, exalted hymns all fused and defined a kind of unity of destiny in the very provisional nature of those times. I peered fearfully around the corner of the doorway and waited for the drama to unfold. Through the legs of the multitude standing in front of me, I could barely see the central aisle and the altar at the end of it. Don Vicente was wearing a threadbare liturgical chasuble topped by a glorious red stole, as befitted the first Sunday in May. A beam of light illuminated his face, and seen from afar in such garb, he looked to me like a scarecrow of the faith. Christ’s cross emphasized the authority of law with its heavy-duty pay-off. Crucified Christ was still looking at the floor. His attitude had hardly changed since the previous night. A man walked into the church and stamped on me, as he hadn’t seen me. “Get out of here, titch,” he whispered loudly, manhandling me out of the way. Four old biddies in black, wrinkled their faces and their veils, turned around in unison and spat reproachful, saliva-free glances in my direction. Shamed by the huge guilt of having been born so repulsively into this world, I had no choice but to draw in my ears and hide behind a confessional, out of the way in a corner of the triforium, that was begrimed by the dust of sins. I could hardly see what was happening, but I clearly heard the big buzz, like a whoosh from hell, that swept out of the tabernacle when Don Vicente opened the door for the moment of the hypostasis. He must have noted some peculiar smell, because he leaned his head to one side before opening it, perhaps wanting to locate the source of those mephitic gases. The children at the communion stood and gaped at the bluebottles that swarmed out, glinting like Satan’s hemorrhoids, hovering in repugnant clusters above their shocked faces. That unspeakable plague immediately filled the vault, and people started clamoring in disgust. The critters comprising that transubstantiation formed a veritable multitude, milling in their thousands, so many, in fact, that their fluttering wings made the walls tremble and cracked the glass in the windows. The insects pirouetted up and down as if craving the sinful stuff the congregation harbored a-plenty in their consciences. It was as if they wanted to be part of the communion, and to die in mouths, which, of course, is what happened in those that didn’t shut in time. Many children crunched them and said they tasted juicy, like cakes soaked in wine or water sweetened with honey. People fled, panic stricken. Some jumped over me, others trampled on me, and all, quite unawares, sorely damaged my spine and brought great suffering upon me. When the church had emptied out, those insects that had blossomed in the matter deposited by my guts, as if by spontaneous combustion, began to return whence they’d perhaps come and disappeared en masse into the blue sky. Only a few were left perching on Saint Roch’s doggy, wound around his tail, thus supplying him with a new, longer wagger, for heaven knows what prosthetic purpose.

Life is an ineffable mystery, with so much baffling arcana. Those of us who are conscious can at least say that, and indeed have the moral duty to do so and to seek out, perhaps in the wonders of existence, the traces of an originating divinity. Gustavo Adolfo indicated as much in the sickly flowers of these lines: As long as science fails to discover the wellsprings of life, and in sea or heaven an abyss that resists reason resides, as long as humanity advances but knows not where it flies, as long as mysteries haunt mankind, there will be poetry!”

Little Santomás was a bastard of the illustrious, nose-in-the-air kind and crushingly able to inflict pain on the helpless. A mule kicked out his teeth when he was in his teens. It struck him because he stuck a firecracker up its anal sphincter, one of the Chinese sort, with a lengthy fuse greased with gunpowder, that were always going off in village fiestas when we were children — the Feast of the Assumption, Michaelmas, May Day, and all those. The mule’s kick landed unluckily for him and cleft his palate. Little Santomás was sent flying when the firecracker went off and spattered shit everywhere. The animal was clearly constipated. Firecrackers are usually harmless, but depending on where and how they are placed, they can do a lot of damage, though bombs do more. A bomb sent One-Eyed Slim and Inspector Esteruelas off along the road to hell. It sucked the blood from their veins. That was in Madrid, in ‘78. Providence mercifully ensured I wasn’t at the site of the carnage; I now know why. Slim said I should go, to keep him company, but I didn’t feel like meeting Esteruelas again. At the time, I was begging on the steps of the church of Our Lady of the Immaculate Conception, right opposite the cafeteria where the artifact exploded. It was part of my commitments to One-Eyed. The Grupos Revolucionarios Antifascistas Primero de Octubre claimed responsibility for the attack. At that time, murders were often carried out in order to destabilize the transition process, but I shall tell you later how much I was involved in such thunder and lightning.

If Don Vicente had lived to a ripe old age, he’d never have stomached those turbulent times, and his heart would have burst in his chest just as the mule’s kick smashed up the face of little Santomás. He believed in divine justice, in a universe hierarchically ordered by an almighty creator, in the enemies of the faith, in the daily presence of the Devil in people’s lives, and in Machaquito anisette. “Clear off, you titchy bugger,” he shouted the day I went to ask to receive the sacrament he should have been sensible and granted; he’d have saved himself the embarrassment of having to go and explain what happened to his higher-ups. Don Vicente was a bastard whose life gradually went sour on him. The Bishop of Albacete called him to account, and he had no choice but to tell him the facts. From then on, he could only see messengers of darkness and try to avoid going to the lavatory. “The sticky vagina of the whore of Babylon has descended upon us with a stench of coriander and a stink of cashews!” he preached on Sundays and obligatory holy days. “Repent and believe in the Gospels!” He went mad. They exiled him to the diocese of Calahorra and he went mad, or perhaps he was mad already. The church had to be exorcized. Incense was burnt in every chapel, and Hail Maries, Credos, and Our Fathers were prayed; it was a lovely ceremony that revealed enormous contrition. The whole village joined the procession, everyone carried a candle, the women were veiled, the men resplendent in clean shirts and ties, and the children silent, respectful, and extremely reverential. Little Margarita was there clutching her black prayer book, as was the worthy, if toothless, Santomás, and others who kept their distance from me, and even my own brother Tranquilino, whose eyes were bewitched by the flames of so many flickering candles. I saw them parade by from the top of a steep slope on the outskirts of the village. The enigma behind their lamentations was sealed in my belly like a secret encrypted in the designs of Providence. These times are contradictory, they are times for the end of time. The world often pretends to be what it isn’t, and everyday reason tends to see through its fantasies, but in the end the mystery of life has to be fathomed by each and every individual, and each should extract the baggage that suits them. In any case, after all that nonsense, confusion, and idiocy spread by word of mouth in the village over the business of the bluebottles, I realized that rather than clinging to someone else’s dogma, one should find what matters in one’s own inner self, the stuff one learns from life itself, the real master when it comes to teaching lessons with a magisterial cane.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «A Bad End»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «A Bad End» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «A Bad End» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.