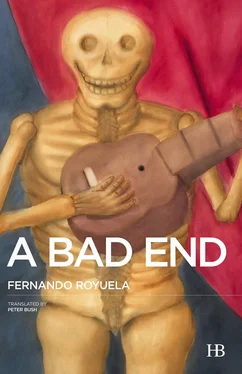

Fernando Royuela - A Bad End

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Fernando Royuela - A Bad End» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2016, Издательство: Hispabooks, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:A Bad End

- Автор:

- Издательство:Hispabooks

- Жанр:

- Год:2016

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A Bad End: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «A Bad End»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

A Bad End — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «A Bad End», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

I could tell you that man’s fate is written by the angels in semen on passion’s damp pages, but I won’t, just in case that, too, is true. Blondie’s memory had disintegrated, and now she only believed in reasons to survive and in the peace of mind brought by not thinking. She told me of terrible things, worse even than burning ants for pleasure or bludgeoning dogs in the teeth for the fun of hearing them howl. My son was absent and stupefied, and though he looked at me, he kept his thoughts to himself, supposing he had any. “What’s your name?” I asked. “Edén, like Comandante Cero,” he replied without a glimmer of pride.

She told me of terrible things. She’d killed men and women with her own hands. She’d sliced through their necks with a blunt knife when they were still gasping their last; she showed no pity to her enemies. She endured five of the nine months of her pregnancy shooting it out in the sierras, then rage won out, and she fell in with a traitor. It was like a little girl’s crush, and softly, softly she saddled him with her offspring. They abandoned the hue and cry of pistols and settled in a little village to the east of Matagalpa. They ran a bar where the troops drank rum to let off steam. Her man drank a lot and then took it out on her with a club. After he’d given her a good beating, he’d switch tack to make a quick buck from her flesh, which he sold on to Sandinista officers for two notes per ride. Whatever they found out from chitchat, they’d pass on to the Contras, in order to sustain life between two lines of fire, and they carried on until, for a handful of coins, the barman finally squealed to the military all they could possibly want to know about their enemy’s positions, plans, and matériel. My son grew up at his mother’s side, bereft of intellect, detached from any upbringing that wasn’t what you learn from the behavior of animals. He’d sulk and spend the whole day sitting by the entrance to the bar, telling the time by the frequency of the customers’ bouts of drunkenness, his mind frazzled by the sun that poured down. Blondie wasn’t aware of the barman’s treachery, and that saved her life. First they beat her in the face with the butt of a revolver, then they thrust the barrel in her mouth and fired it without a bullet, to give her a fright, or perhaps it just failed to fire. One of the guerrilleros wanted to slice off a nipple as a souvenir with a huge curved dagger, but by that time, they’d calmed down, after having fun executing the traitorous barman. When they tired of beating her, they buggered her unenthusiastically. They did it right there in front of the boy, while flies, those angelic insects, buzzed over his little head with proboscises smeared in lizard shit. Before that, as I said, they’d leisurely taken out their anger on the squealer. They put a hood over his head, a rope round his neck, and after breaking every bone in his body, they swung the little life left in him from a tamarind tree soured by toucan piss.

What wouldn’t you do for love — provoke a natural catastrophe, undergo genetic alterations, even participate in sporting events? When it comes to love, the will is hallowed, and one goes into absolute self-denial to the point of annihilation. Blondie’s body was covered in the scars from the blows meted out by the barman when he possessed her. Bastards sometimes sing from the same hymn sheet, and at others not so much, one can never know. When it comes to love, one would go round the world in rope sandals, or selflessly allow one’s every other finger to be amputated. Blondie’s skin was still marked by the gashes the barman’s belt buckle left when he dowsed her desire to up and leave that tropical inferno. For a moment I imagined her naked on the earth floor of the bar, laid low by a soporific siesta, sniffing the shadows with her dilated nostrils, perhaps with the other guy next to her, crooning cheap, dirty lyrics in her ear and letting his hand wander whimsically over the ravaged geography of her thighs. I imagined her yet again feeling in her flesh the simmering crack of the whiplashes, and I was reminded of the rage with which little Santomás tore off strips of my skin that night, and then I glimpsed three or four drops of blood dripping down his side and, in a shocking fusion of pain and desire, melting into his sweat. My son later saw his putative father dead, swinging from one side to another, his head half-severed by the knife that was the rope. Croaking stone curlews flew close to his danse macabre. The scene must have drained his neurons, because the boy didn’t burst into tears, he peed himself and became mute forever.

Humiliation is a visual expression of defeat. The humiliated adversary secretes defenselessness and generates pleasure in the executioner. I humiliated Blond Juana twofold, first by sinking the seed of my descendent in her flesh, and then by purchasing at the age of nine the life it engendered. “I’ll look after the boy on condition that you never claim him and never see him again. At the same time, I’ll rescue you from poverty and pay you a pension so you can get back on your feet, if that’s what you want, in a life without a past, where neither he nor I exist.” She accepted. I was also sold on as a child. They say history repeats itself. I never told my son of the circumstances that brought him to me, nor did I bother to inform him that a dwarf was his real father. I was resigned to seeing him remain locked in the hermetic box of his memories and sent him to London, to a renowned, highly recommended institution where he’d get the best treatment possible, which is the sort that one pays for quickly, without any wrangling. He didn’t react when his mother bid him farewell forever with a kiss poisoned by remorse. He is stolid, impenetrable, and blank. He inhabits inner universes and only very occasionally shows remote interest in trivial or ephemeral matters. It’s a sorry business to walk by his side. His companionship is pure ice, and I often wonder whether the grave wouldn’t at least relieve him of that lethargy to which his autism condemns him. However, perhaps it is his fate to live in imagined worlds where the rules of logic don’t exist and passions don’t unleash their designs. Perhaps that world is truer than my own, the one where I find myself now, alone, empty, scrutinized by you, waiting for nothing else but the endpoint of my own consummation.

Pizzas are made from flour dough, baked in special chambers, strewn with tasty dressings, chewed with quiet relish, and, once digested, are expelled from the anal sphincter, transubstantiated into excrement. Levels of reality can be multiple and don’t necessarily have to pass through the digestive tube of what is explicable. Dogs, fools, and poets intuit the worlds beyond what surrounds them and behave accordingly: the first howl, the second slaver, and the third make rhymes of passionate non sequiturs nobody appreciates in the slightest. I told the doctors; they mainly ignored me. My fool of a son spent the morning apparently engrossed in a painting hanging in a room at the Tate Gallery. We’d just lunched at Fortnum and Mason’s on cheddar and cucumber sandwiches, which Edén barely touched. He was still too accustomed to eating the quasi-rotten food seasoned with chili his mother offered him. For a long time he made no sound that gave proof of thought or an intelligible expression of will. Whenever I go to London, I take him for a stroll along Oxford Street, or have fun accompanying him to see the caged animals in the Regent’s Park Zoo. We also pop into the odd big department store, where I usually spend vast amounts on toys I send to the sanatorium with a view to bringing some relief to the inner solitude that fences in the brains of the children shut up there. I often take him to museums, to familiarize him with genuine parameters of beauty. He doesn’t flinch or get upset; he follows me and says nothing. That morning in the Tate Gallery, he sat absorbed in that painting and didn’t make a single gesture or murmur, he only let out a fart that flooded the room with an intolerable stink. The people looking at pictures around us turned their heads and eyed us, visibly annoyed by the bad odor — perhaps they were concluding that the stench originated from me and my deformities — when suddenly my son, as if struck by an epileptic fit, went into a purple frenzy of verbal diarrhea and began shouting out gutturally, as he pointed his index finger at the painting he was looking at. “It’s you! It’s you!” he cried frantically. I didn’t react right away, I was so surprised to hear his voice, and it took me a few seconds to cotton on to what was happening. I had to stifle the boy’s hysteria with a couple of slaps, which appalled the public there. “You are that dwarf,” the child under sentence kept repeating, and in fact he was right, because that mess of floating entrails hanging on a wall of the Francis Bacon retrospective was yours truly, or rather, yours truly thirty years ago; that handicapped youth whose decomposing guts the pink-cheeked artist had felt like painting in the twilight brine of the Costa del Sol.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «A Bad End»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «A Bad End» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «A Bad End» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.