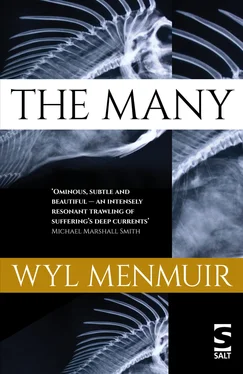

Wyl Menmuir - The Many

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Wyl Menmuir - The Many» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2016, Издательство: Salt, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Many

- Автор:

- Издательство:Salt

- Жанр:

- Год:2016

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Many: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Many»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Many — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Many», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

From a distance, Timothy’s progress is barely visible, and he inches across the landscape, as though he is swimming alone in a wide featureless ocean with no sense of scale against which to measure the distance he gains.

Ethan is overwhelmed by the desire to shout out across the water to him, to warn him off, though he knows the distance between them is too far, and he wonders whether all hunters feel this impulse when they see their quarry. He watches until Timothy disappears where the road dips down, and though he waits and continues to stare at the coast, he does not see him again, and it occurs to Ethan that he has fabricated this event, that he has been out on the water too long to tell the difference between fantasy and reality.

5. Timothy

ON HIS RETURN, Timothy’s thoughts are all renewal and progress.

When he arrives back from his run, he stands between the house and the car, which he had parked two hours earlier. Not wanting to disrupt his new enthusiasm, he gets in at the passenger door and changes back into warmer clothes, then looks out through the windscreen at the kitchen door. He is not ready to go back into the house yet. Instead, he walks slowly down through the village to the row of houses where he remembers he and Lauren had stayed. They had decided on their destination by moving their fingers together over the map, his hand laid over hers, as they skimmed their fingertips across the coast until they found a place with a name that pleased them, a place where they could spend the time together just being themselves. He cannot now remember the name of the hotel in which they stayed, though the rudeness of their host is still fresh to him, as is the way in which he ushered them out of the bar area as soon as they arrived.

‘No room here,’ the landlord says as they enter, loud enough to stop the conversations going on across the room and for all eyes to turn towards them. They wonder whether they have got the wrong place. They freeze on the threshold, half in and half out of the bar, with their two bags slung between them, and the landlord waves them away and goes back to wiping the bar down with a cloth, eyeing them from beneath thick eyebrows.

Outside, they are getting back into the car when they see the landlord appear again from a fire exit at the side of the building. He waves them over and when they do not come straight away he hisses something at them and waves again, this time with more urgency.

‘Come on. Quick. Can’t let them in there know I’ve got rooms empty. I’ve told them there are none free,’ he says. He stares at their mud-spattered clothes with open disgust as they approach across the car park.

‘That’s okay, it’s obvious there’s a mistake,’ says Lauren.

‘No. No mistake. You just come in this way. I’ll leave this door propped open and you can come and go through here. It’s forty up front now and ten more if you want breakfast tomorrow.’

He leads them through the side door into a dimly lit hallway and they stand together awkwardly cramped in the small corridor as Timothy fumbles in his pockets for the money. Timothy has the vague suspicion they are being mugged and that they will be ejected from the side door the moment he has handed over the cash. There is a door tiled with small panels of obscured glass a little way into the corridor which leads through to the bar area and the landlord pushes them past this and to the foot of a flight of stairs.

‘It’s up there, top of the stairs. Walk quiet, mind.’

Lauren and Timothy exchange glances, but they are too tired to argue and they have handed over their money now. From what they had seen of the village as they drove in earlier that day, they are going to struggle to find a room anywhere else. They start up the stairs and the landlord follows closely behind. At the top he gives them a key, attached to a heavy and oversized wooden key fob.

‘You’ll find everything you need in there.’ He points to the furthest left of four doors which lead off the landing ahead. ‘That one’s yours. Bathroom’s through the door on the right. Don’t worry about the other two, they’re mine. Don’t make too much noise on the floor. Them down there can’t know you’re here. Breakfast’s at six and you’ll need to be gone by nine.’

He turns to go and halfway down the staircase turns and hisses back up, ‘And use the side door.’

‘Can we come down for supper?’ Lauren asks.

The landlord comes part way up the stairs towards them.

‘I’ve already told you, steer clear of the bar, we’re closed for food. You’ll find no food here, not this time of the evening. I told you, I don’t want you causing trouble.’

And with that he is heading back downstairs. Timothy wants to follow the landlord and hand the key back to him, but he has already turned the corner through the glass door and they decide going into the bar would be a bad idea.

At Lauren’s insistence they jam a chair under the door handle when they turn in to sleep. It is dark outside now and there is nowhere else for them to go. As Timothy opens their bags, Lauren walks around the room and touches all the curtains in turn, the bedspreads, the lampshade on the bedside table that sits between the two single beds. All share the same pink floral pattern, a pattern that clashes with the garish swirls of the orangey-brown carpet. They lift out the side table and lamp and push the two beds together, trying not to make noise for fear they will bring the landlord back up the stairs. Lauren arranges the single duvets so they will cover both of them.

Above the beds, a small, gaudy painting of the Virgin Mary, all blues and golds, stares down at them with sad eyes from beneath her oversized crown. The paint is peeling from the picture and the face of the child she carries is obscured. Timothy and Lauren kick off their shoes and climb into bed still fully dressed beneath the textured nylon sheets. They laugh beneath the floral covers at the strangeness of the place and listen to the dull sea of chatter from the bar beneath.

The next morning, they wait to be served breakfast in the empty bar area surrounded by the dark wood tables off which shines a harsh morning light.

‘Could you do me two poached eggs on brown toast?’ Lauren asks the barmaid, who looks to be about sixteen. The girl stands in between them and the window out onto the road, which throws her into a harsh silhouette.

‘We don’t have brown bread, just white. And we don’t have poached eggs. We’ve got scrambled or fried.’

They wait until the girl has left the room to laugh, though they cannot be sure she has not heard them. When their breakfasts arrive, both Timothy and Lauren leave them untouched. The food sits, surrounded by a halo of grease, on plates that have been washed too many times to serve food anyone would want to eat. When Timothy returns from his morning run, he finds Lauren has once again blocked the bedroom door with a chair and he waits as she gets out of bed and pulls on a t-shirt to let him in. Keeping the game going, he steps inside and replaces the chair. They are trespassers in a strange place.

Timothy walks along the street twice before he realises the hotel is no more. He finds the building from the screw points where the sign had been affixed to the wall, and it looks to him now as though it has been split into two, maybe three houses. There are more doors and windows than there had been, clumsily punched through the old walls. Through one of the windows he sees there are still tables and chairs in a room too large for a house and he figures there is still a pub here, though there is no real sign of that from the outside.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Many»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Many» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Many» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.