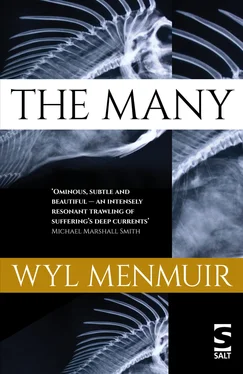

Wyl Menmuir - The Many

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Wyl Menmuir - The Many» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2016, Издательство: Salt, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Many

- Автор:

- Издательство:Salt

- Жанр:

- Год:2016

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Many: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Many»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Many — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Many», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

He sits on his heels a few feet from the water, watching the almost imperceptible lapping of the sea on the stones, and feels a wave of anger cross him, anger he had hoped had been excised by the run and the shock of his immersion into the sea. He picks up a handful of the smooth grey pebbles and hurls them into the still water. He watches the ripples as they spread out, intercept each other, distort and fade back to stillness. It is a mistake.

3. Ethan

THROUGH GAPS IN curtains and in stolen glances as they come within sight of Perran’s, the village watches Timothy as he passes on his walks and runs, and as he carries out, over the period of several days, the tattered contents of Perran’s house. They watch as he drags out a filthy carpet, which they see he has hacked at to make it small enough to roll and carry. He emerges from the house with arms full of dusty wallpaper and curtains and struggles under the weight of a rusting refrigerator as he hauls it out through the kitchen door to join the pile of furniture in front of the house. Some of the younger villagers speculate Timothy will set light to the pile like a beacon, as they do on the hilltop above the village once a year midwinter, though he never does and the teenagers don’t have the bottle to do it themselves. As Ethan thinks on it, he wonders whether he might have done so at one time.

Those who remember Perran well look past or above the pile of furniture, and think they do so out of respect for him, though it is more for their sense of disgust and shame at the state of the items they see laid out in the harsh winter light, and they do not talk of it. The pile of rubble in the garden increases in size, and then, as rapidly, reduces until it is gone, and all that’s left of it are small ribbons of linoleum, coloured paper and plastic, which catch in the branches of the hedge at the foot of the garden like tributes to an old god.

They see Timothy at Perran’s windows as he strips back paint from the sills, as he breaks up tired furniture in the garden, and as he runs out and back along the coast road. They count the minutes or sometimes the hours he is gone and obsess over where he might be until he returns and talk about him in the café and the pub. Ethan tries to keep his eyes on the horizon, away from Perran’s house, and avoids being drawn into conversation about the incomer, though he follows him more closely than any of the others. He avoids everyone during this time and sticks to his solitude and his boat, torn between staying to watch what Timothy will do next and the desire to be far away from him and from the memory of Perran.

The regulars wait for Timothy to appear in the pub and they are affronted when he stays away. They see him standing in front of Perran’s house, looking out to sea, and sometimes down by the rocks on the shore’s edge. He is fodder for rumour and they know so little of him, and stories emerge as to who he is, this newcomer who arrived late one night and shut himself away in Perran’s house, gutting away at it as hard as the men in the photographs gut fish on the beach wall.

They lower their voices when Ethan is close by, he notices, out of respect, or awkwardness, he is not sure, but he hears the stories as they spread. Timothy has come to resurrect Perran. He has come to destroy Perran’s house, to erase his memory. He’s come because that’s what upcountry folk do, to replace the drudgery of the city with that of the coast. He has come to save them from themselves, or to hold up a mirror to them and they will see themselves reflected back in all their faults and backwardness. He has come to change them, to impose himself on them, to lead them or to fade into their shadows.

When the boats leave in the evening, the crews see the lights on at Perran’s and when they return in the morning darkness they see the lights are on still, when there are no others lit in the village, and they speculate as to who he is and what he is doing here.

Timothy’s car disappears sometimes for days at a time and the village counts the hours until it returns, usually late at night, sometimes with lengths of wood strapped to the roof, with boxes in the boot, and always fuller than when it left. A few weeks after Timothy first appears in the village, the car returns with a trailer, on which arrives a table, two small wardrobes, a small bookcase and a chest of drawers.

The first time Ethan sees Timothy Buchannan up close is out past the village on a blowy mid-morning, early December. Ethan had seen Timothy leave Perran’s by the side gate and now follows him at a distance further up the hill. He loses sight of Timothy and almost walks past him, but sees the bright blue of his walking coat a few minutes later. Timothy is crouching beneath one of the field walls off the track at the top of the hill, protecting himself from the rain-heavy wind. With the hood on his waterproof up, he is talking into a mobile phone, his voice raised against the wind, and Ethan hears fragments of the conversation as he walks past.

‘It, it still needs work… Yes, a bit… Okay, a bit more than a bit, a lot… How are you feeling? And? When are you going to come? Yes, it’s getting there. Yes, still some to go… I know, I know, you too.’

Timothy has not noticed Ethan’s approach and Ethan slows his pace as he continues up the track away from the village.

‘No, it won’t be ready by then. I’ll come back for a few days and we can spend it together. Promise. I know. I want you to be here too. Just a bit longer, I’ll make it right.’

There is a silence and then ‘Shit. Shit. Shit.’ Timothy unfolds his limbs from their crouch by the wall and emerges from behind the stone wall, waving his phone in the air as though he will be able to catch a signal from the passing wind.

Ethan walks a way further before turning back on himself and down towards the village again and when he passes the wall again he sees Timothy has gone.

The afternoon finds Ethan on the beach looking out at the container ships three miles off shore; skeletal for their lack of cargo, idle sentries to an empty coast. The ships come in and out of view as pulses of rain and cloud push through to the shore, whipping up the spray and the waves. He cannot settle and alternates between looking out at the horizon and glancing up towards Perran’s, as though a magnet drawing his gaze that way is being turned on and then off again by a bored child.

Clem, keeper of the boats and their crews, has refused to operate the tractor and they are confined to the shore, as the container ships are confined to their positions on the horizon. There are children in the grounded boats now, some in the derelicts, crawling over the rusted and storm-damaged hulls, and some in the working boats, swinging themselves up onto the roofs of the cabins and throwing loose pieces of tackle at each other across the gaps in between the boats.

They don’t play in the water any more. There’s no playing or swimming in the water, not if you don’t want to end up sick, or sterile. A profusion of biological agents and contaminants is how the Department for Fisheries and Aquaculture described it in one of their many communications, a note which is now affixed with the others, mouldering on the notice board in the winch house.

After Perran died, there had been talk of Clem taking over his house, it having the clearest view of the boats returning and Clem’s having none. But Clem resisted, said Perran’s place needed rest after the grief the house had seen. He didn’t say it would feel like bad luck to move in there and no one else pressed the case. Anyway, he had a radio and they could raise him on that of a morning if they needed to.

Later in the day the worst of it has passed, leaving behind light rain and a low tide. The waves are untidy and unsettled by the memory of the earlier storm and a group of children is gathered on the beach, armed with sticks. They are crowded round a huge jellyfish washed up onto the stones. It is spread flat, about six feet across, transparent and run through with thin red veins. The children bounce stones off its back and dare each other to touch the body, though the furthest they dare go is to poke at it with their sticks.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Many»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Many» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Many» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.