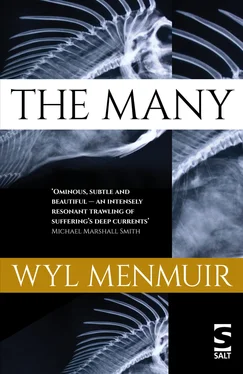

Wyl Menmuir - The Many

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Wyl Menmuir - The Many» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2016, Издательство: Salt, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Many

- Автор:

- Издательство:Salt

- Жанр:

- Год:2016

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Many: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Many»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Many — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Many», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

It has been a long while since Ethan has come up this way, since he has stood outside Perran’s house. He walks around to the front of the house, stands at the door and listens, working out what he will say if he is confronted, but he can hear nothing from inside. The curtains are drawn, as they have been these ten years gone. Ethan walks away from the house and touches the car as he passes it, as though it might dissolve in the air like the smoke he had seen rising from the chimney.

The next day, Ethan motors out of the cove in a smaller boat he has dragged down the beach himself, and pulls up the pots on the fixed lines. It’s ritual rather than function. The pots always come up empty, though the rumours and predictions the fishermen spread among themselves in the village are still strong enough to keep him coming back. He does not bother to rebait them, but rinses out the old bait and checks each of the pots for damage before he drops them back over the side.

He finds he does not want to head back into the cove and have to confront the smoke rising up from Perran’s again, and instead of turning the boat back towards the village as he had planned, he steers a course along the coast for a mile or so, then heads out into open water, out towards the line of stationary container ships. The ships are spread out evenly across the horizon, as though they have lowered between them an enormous seine, an impossibly long net they are waiting to close. He cuts the engine back to a low growl and considers the line of ships for a few minutes. As he looks at them, he has the feeling of being hemmed in from all sides and a thought rises in him that he could break through the line of ships, that he could break one of the unspoken rules of the fleet. He supresses the thought, concentrating instead on the body of water in between the boat and the ships, looking for shadows in the water. He is close enough to the ships now to feel observed, though he cannot recall, even when they first arrived, ever having seen lights or any movement from the huge, rusting hulls. The men in the fleet ignore their presence as far as they can.

Ethan has been fishing for himself since he was twelve, and helming Great Hope since he was nineteen. With his thoughts still floating out by the container ships, looking through the wide gaps between the ships, he cuts the engine and opens the storage box at his feet. From within a tangle of netting, buoys and shackles, he pulls out a fishing rod, the one he used when his father first took him out on the boat. He threads a hook onto the line and baits the hook using some of the rotting meat he had not used to bait the pots and casts the line out. He braces the rod between the gunwale and his leg and rolls a cigarette.

‘I’m fine. I’m fine.’

Perran is still breathing out seawater from his mouth and nose and his hair is plastered in thick clumps against his head. Though there is no light on the shore, and what light there should be from the night sky is shrouded in a thick cloak of clouds, Ethan can see Perran is shivering beneath his jumper, which is now stuck fast against his chest.

‘I haven’t found him either. We need to go back. No point now, not in this.’

Ethan has to shout above the wind to make himself heard. Perran shakes his head and keeps on shaking it and there might be tears in his eyes, or it might be the salt water, or the rain. The wind, howling around them, is pushing him on.

‘He won’t be out along the rocks, or on the beach. Not in this. Go back to the house. I’ll go up on Lantern Street, see if he could have got up there,’ Ethan says. ‘Go home.’

Perran’s gaze follows the line of Ethan’s outstretched arm to where his dog may or may not be, and he turns his head back to look down the beach. It is mid-tide, though with the size of the waves and the height of them, it could be any tide. They can’t see the waves as they approach, just the final white crash as the swell collides with the stones on the beach and drags them back out through the cove’s entrance.

Perran pulls wet sleeves down over his hands and walks off in the direction of his house, though he turns back to look at the water several times. Ethan tries to conceal his concern, to reassure him.

‘I’ll find him, Perran, I will. Go on home.’

Ethan watches until Perran is out of sight and walks along the coast road to the turning up Lantern Street. The dog will already be back at Perran’s, he already knows that. The two of them will laugh when they see each other the next day, as though their search the night before had been a joke. Ethan will ruffle Perran’s hair and the fur on the back of the dog that was not lost all along.

He passes up by Perran’s house as he makes his way home. The house is in darkness and he assumes Perran has taken himself to bed, to be up for the boats.

In the morning, Ethan is woken by the sound of knocking at his door. After answering, and still thick with sleep, he dresses hurriedly and makes his way down to the beach, where he finds most of the boat crews standing in a huddle by the winch house. A couple of boats have launched, but the rest are uneasy going out with no Perran there and no answer at his house. No matter how bad things are with the crews or the conditions, he is always there for the boats. Always.

Later in the morning, when still he does not appear, the fishermen organise themselves into search parties, Ethan among them, and they comb the beach and the empty sheds, and then walk up through the village calling for him. Ethan tells them about the events of the night before and they reassure him that Perran will turn up.

It isn’t the search party that brings news; it is one of the crews on the boats returning who calls it in. They see his yellow waders, bright against the rocks beyond the mouth of the cove, and call it through on the radio.

The operation to retrieve Perran’s body is a major one. The tide is on the rise again and the rocks are already part submerged. The same rocks make it difficult to get a boat close in and the cliffs are too steep, too unstable to descend. In the end, two of the men take a small rowboat out through the cove mouth. There isn’t much choice with the tide as it is, and Ethan watches with the others from the shore as the pair struggle against a sea still heavy, a hangover from the storm the night before.

When they bring Perran back in, they have covered him with a tarpaulin. The men on shore run forward and drag the boat up onto the beach and, when it comes to rest, one of the men pulls the tarpaulin back and Ethan sees he is curled up in the bottom of the boat like a child sleeping.

As the light starts to fade, Ethan reels his line back in and packs the fishing rod away. He pushes, from where they have been accumulating, a small mound of cigarette butts over the gunwale, and the congealed island of ash and paper bobs on the water and floats for a while before the waves start to break it down into its constituent parts. He looks out towards the container ships again, uncomfortable from looking down into the water for so long, and feels again the unfamiliar pull from beyond the ships and with it a dread he cannot place. He turns away from the ships and sets a course back towards the village.

Ethan is making his way in along the coast when he sees a man, his bare skin pale against the rocks on the shore a mile or so from the village, lowering himself into the dark water. He watches as the man stands thigh-deep in the sea and then he drops suddenly and his torso disappears and Ethan loses sight of him for a moment, though it is only a few seconds before he sees him climbing up the rocks towards the road.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Many»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Many» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Many» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.