Emma shook her head. Twenty thousand dollars. It wouldn’t last long, she thought. And yet twenty thousand dollars was what her whole life was worth. She’d walked through every room in the house that night, trying to memorize the details of her past. But as soon as they took the check, the past started to dissipate. Standing here now, it was hard for her to remember anything but their decision to leave.

Henry came out the front door carrying two suitcases, which he threw in the back of his pickup. The truck bed was stuffed to the point of bulging; throw in anything else, Emma thought, and the suspension would give way.

“That’s it,” Henry said, and lit a cigarette. The smoke was invisible against the early morning sky. “All set?”

Emma nodded. Henry acted as if they were merely going for a spin. She looked up and down Topeka Drive and saw a forest of “Sold” signs. Last night, she passed the park where Dorothy played. The trees had been uprooted, and a team of FEMA workers were frantically constructing a tent city on the newly cleared land. It was so much like January 1994 that she pulled the car over to catch her breath.

When she got home, she had begun packing immediately, losing herself in an attempt to forget. The news contained reports of more looting, and Emma felt tears welling in her eyes. She had ridden her bike on this street, and watched her daughter do the same. She wondered if they’d ever come back to this place, and if they did, what would remain. Would the ordered pattern of houses and streets survive, or would they all be shaken away?

Henry went around to the pickup’s cab and climbed inside. After a moment, the tinny voice of a traffic reporter alerted them that the 405 was backed up all the way from the 101 to the 5. Henry took a drag off his cigarette and squinted at the sky.

“It’s getting late,” he said. “Why don’t you wake the little girl?”

In Honolulu, Charlie met a leathery-faced man who sold him sixty pounds of plastic explosives — enough to sink a battleship. Then he chartered an amphibious plane that could land in the small natural harbor of Lui and coast toward the shore. Fifty yards from the island, he lowered an inflatable raft into the warm Pacific waters, threw down his gear, and told the pilot when to pick him up on Thursday. Then the plane took off, and Charlie realized he was utterly alone.

On the beach, Charlie took inventory: food, water, flashlight, drill, generator, laptop, and explosives. He began to trek inland. The ground was hilly, with outcroppings of volcanic rock rising in irregular formations, and lush, overhanging growth so dense it obscured the sun. Humidity made the whole place feel like a sauna, and before he’d gone half a mile, Charlie stripped down to his underwear. Grace’s presence, like an invisible spirit, hovered at his hand, and he imagined what it would be like if she were there, running naked with him in and out of the sea.

But there would be plenty of time for vacations. Briefly, he was struck by the old familiar doubts — that what he was trying to do was absurd, a small man’s attempt to tamper with the forces of nature. Then Grace’s face returned to him. She was in Los Angeles, he thought, and he appreciated the fact that it meant he had no choice but to succeed.

Eventually, Charlie came to a clearing with a dusty covering of brittle soil. This is it, he thought. He checked his compass and the coordinates of his map. His stomach began to flutter, accompanied by a clenching of his sphincter and a tightening of his balls. To his right, like a revelation, was the shape of a small, dormant volcano, its rocky sides rising in jagged minarets to the sky.

Charlie threw off his backpack and took out his equipment piece by piece. He turned on the laptop, and an image of Lui appeared on the screen, along with specific coordinates, angles of entry, and depths of charge.

He spent a while comparing the computer simulation with the actual landscape, walking off distances and doing tests of the soil. On the southwest side of the volcano, Charlie went to work. The drill whined like a dentist’s, its three diamond-tipped bits glinting in the sun like bad teeth. He looked at his watch. Wednesday, December 27, three-seventeen p.m. Less than twenty-nine hours to go.

Thursday morning, Grace was awakened at six-thirty by the phone. She had been dreaming of Charlie, and when the ringing sliced its way into her consciousness, her first thought was that he was dead. When she got to the living room, however, it was Ian’s voice emerging from the answering machine, plaintive and petulant.

“Come on, Grace,” he was saying. “I know you’re there.”

She turned the volume down, but the damage was done. Back in bed, she couldn’t sleep. Pictures swirled in her mind: Charlie trekking through the middle of nowhere, without sufficient food or water. With explosives strapped to his back. Charlie stumbling. Charlie falling.

Shit, Grace thought. She took off her nightgown, pulled on a pair of jeans, and caught a glimpse through the open window of the sun rising in the east. The sky was clear as ice; the flanks of the mountains stained rose with spreading light. Tomorrow, she thought, it could all be gone.

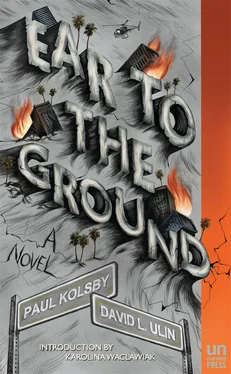

Grace walked up Spaulding toward Melrose, listening for even the slightest sign of life. They were reporting violence, but here the street was deserted, with a single car parked at the curb. In the last few days, she had watched her neighbors leaving town, even as her life continued to be possessed by Ear to the Ground. I should call Semel, she thought. When I get back.

Nearly all the stores were shuttered on Melrose, strips of tape X-ed across windows as silent supplication to the gods, or protection against them. Cops stood at intersections, along with members of the National Guard. Grace was surprised to find the Martel Avenue newsstand open, and as she plunked down her fifty-four cents for the Times she wished the proprietor good luck. One section today, twelve pages, with no advertising and no sports or lifestyle sections. Just earthquake news.

When Grace returned home, Navaro was sitting on the front steps having a cigarette.

“Smoke?” he asked her, gesturing with his pack.

“I’ve got my own, thanks.” She shook out a Merit, and accepted his offer of a light.

“I’m surprised you’re still around,” he said.

“What about you?”

“All I got’s right here.” Navaro waved loosely at the building. “Somebody has to protect it.”

Grace almost laughed. “From who?”

“You watch the news? There’s animals out there. Taking what ain’t theirs.” His mouth twisted into a snarl, and all of a sudden Grace could imagine what he must have looked like as a young man. It wasn’t an altogether unattractive picture, and she found herself starting to get drawn in.

“Anybody tries to fuck with this place, they’re gonna get a big surprise.”

He leered at her conspiratorially, before letting his face settle back into a mask of stone. Grace could see him waiting, like a little boy, for her to ask what he had in mind. Give him his thrill, she thought, and smoked for a moment. “Surprise?”

“That’s right,” Navaro said. He raised himself up, and became an old man again before Grace’s eyes. He put one hand on his chest and with the other fumbled with his jacket, removing something from the pocket that looked like a length of iron pipe. The sun glinted off the metal, and she had to squint. Then she recognized a barrel and a chamber, and she realized with a shock of horror that her landlord had a gun in his hand.

By six-forty-five Thursday evening, Charlie had drilled twenty-three one-inch-diameter holes in an octagonal pattern, all seventeen-and-seven-eights inches deep. Twenty-three detonator pins, one in each hole, had been lowered, and held in place with plastique — soft but heavy — and frightening to the touch. It would be the ultimate irony for Charlie to have come this far, and end up as nothing but a fine red mist.

Читать дальше