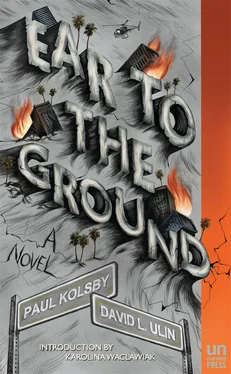

Virtually everything had been affected by the coming disaster — and every corner of the nation’s second largest metropolitan area experienced this psychic foreshock. It was in such an atmosphere that Warner Brothers opened its $210 million extravaganza Ear to the Ground.

At the premiere, Bruce Springsteen’s “Shaken Up” played softly in the courtyard at Mann’s Chinese. Behind police barricades, throngs of rubberneckers and leaner-inners and know-they-can’ts reached for Henny Rarlin as he got out of his limousine with an unidentified woman — not his wife — and assumed a camera smile. A lot was on Henny’s mind. This fucking movie could kill him. It could send him to the minor leagues, or worse: Finland, to make documentaries on Laplanders. Henny had been drinking since noon, and as he strode cotton-mouthed down the red carpet, he thought only of reaching his seat without incident.

Another limousine yielded Ethan Carson with Sandra Bullet, who broke her heel as she got out, and recovered marvelously by enacting a Chaplinesque pantomime, in which she attempted to hide her imperfections from the fans. Sandy hoped her cameo as the seismologist’s wife would alter the lovable-but-slightly-naive-girl image she’d acquired. As flashes went off around them, Ethan spent his energy considering whether people would actually think he and Sandy were an item.

Grace came with — she had to laugh — Matt Dillinger, who was exactly like the character he portrayed in Lasso the Pharmacist. As a fireman in Ear to the Ground, he repeatedly risked his life, always emerging sweaty and covered with soot. Grace wanted to come alone, but that was vetoed by Ethan. “What about your seismologist?” he asked her, mentally tallying the publicity Charlie’s presence might generate. “Out of town,” she’d said, and suggested Dillinger.

Ian couldn’t have guessed they would boo him. He’d thought, given the circumstances, the applause might be strange, maybe meager, maybe even nonexistent. But, as the third-from-last title—“Written by Ian Marcus”—faded up, the catcalls began.

Ian sunk down in his seat and looked around for his date. Her name was Maria, and she was very pretty, but she was nowhere to be found. The Jon Kravitz lawsuit had made page one in Variety for a full week, and Ian was now notorious in the town that had once ignored him. Listening to the tumult, he wished silently for some kind of reprieve. Then, to hide his identity, he began to boo along with the crowd.

Grace had seen the film plenty of times, so she relaxed and let herself drift. Almost immediately, Charlie’s image came to mind. Grace could hardly remember his face, but she could see his chest clearly, with its strawberry tuft of hair. She liked that chest, and she remembered being surprised when Charlie had taken off his shirt and propped it on her bedpost. Quite surprised.

The movie was predictable but entertaining. Special effects — especially sound effects — were tremendous. At the climax, as the earthquake hit and walls tumbled in on an audience watching a movie about an earthquake, the effect was suitably disturbing. So much so that, when the lights came up, those Hollywood luminaries remembered it wasn’t just a movie.

For this reason, an un-native hue of resolution fell over the afterparty.

People drank less than usual, but smoked more cigarettes and pot, which entailed walking to the far end of the soundstage and cramming onto a sliver of patio. It got so popular out there that the caterers peeled the tent back as much as possible without causing it to collapse on itself.

Bob Semel sat near the bandstand with his division heads, projecting grosses. Reviews were only a minor consideration, but if the earthquake was a dud, they were in deep shit. This picture should have opened a month ago, and Semel knew it. Now all he could do was airlift the studio to Tucson, Arizona, and hope for the worst.

Around the room, the talk was earthquake, earthquake, earthquake. “Look for a slew of movies about ’em,” Sterling Caruthers told a pair of actresses.

“You a producer?” a bobbed redhead asked him.

“Among other things, yes. I helped produce this film.”

“Really?” the other one asked.

“I’m director of the Center for Earthquake Studies.”

“A producer and a director!” The redhead made a joke.

“The truth is”—Caruthers took her hand—“I like the movies. I just signed with Warners to consult on scientific matters, with a first-look deal on projects of my own.”

“Exciting !” the redhead said.

“Listen,” Caruthers continued, “I’m leaving in five minutes, and thought you might like to come with me.”

“Uh … where?”

“To a press conference, briefly. Then, hopefully, to a nice supper.”

The redhead looked over at her friend.

“I just need to leave, that’s all,” Caruthers said, and smiled gently.

“Sure,” she looked back at him. “That sounds fun.”

Charlie Richter sat in a cab driving down La Cienega toward LAX. Beside him on the back seat was a rucksack containing some clothes, a laptop computer, a surveyor’s compass, and nasty-looking drill bits designed to cut through volcanic rock. In his hand, he held the photo of Grace he’d stolen so many months ago, her face as unreadable as the first time he’d seen it.

Charlie didn’t regret telling Grace about the retroshock, nor about the trip to Lui. He also didn’t regret what happened after they’d finished talking, although it had complicated things. Now, on his way out of town, he felt as if he were leaving a little piece of himself behind. For the first time since he was a boy, he felt like Los Angeles was home. At the same time, he was more than a little worried: L.A. could become a very dangerous place in the next few days.

The cab’s AM radio spilled a litany of panic into the air. Every flight out of LAX, Burbank, Ontario, and John Wayne had been booked through Thursday night, and all four airports would be closed on December 29. It was impossible to find a seat anywhere — even on a bus or a train. The freeways, too, were overloaded: If you took the 10 east from La Cienega, it would take two hours to reach downtown. All across Southern California, entire neighborhoods had become modern ghost towns. There were isolated reports of looting, and clusters of small fires dotted the night sky.

At the airport, the gridlock was impossible. So Charlie paid the driver and walked around the terminal buildings until he found Hawaiian Air. Wherever he looked, young men and women in white robes walked in wide circles, chanting and holding up signs: “The End Is Near” and “Welcome to the Apocalypse.”

Charlie had heard about these people, these apocalyptics, who, in the last week or so, had actually begun arriving in L.A. And who knows: they could be right. But Charlie knew, if everything worked out as planned, they would once again be denied the chance to glimpse the face of God. It was not his intention to interfere with their faith but, in the end, faith was such a tenuous thing. Charlie’s was in the perfectibility of science, the way everything, if examined properly, could be codified and explained.

At a quarter to seven on Wednesday morning, the sun was barely a rumor, daylight gray and streaked with purple, silent but for a tentatively squawking bird. In the driveway of 1939 Topeka Drive, Emma Grant stood wiping her hands on her sweatpants, staring at the house.

It had all happened so quickly. One minute, she’d been sitting at the kitchen table, staring at the bill of sale; the next, Henry was standing over her, transfixed by the sight of that twenty-thousand-dollar check. She hadn’t heard him come in, but Frank Baum sure had, and within half an hour, the paperwork had been signed, the money turned over, and Henry was talking, talking — always talking — about how they were rich.

Читать дальше