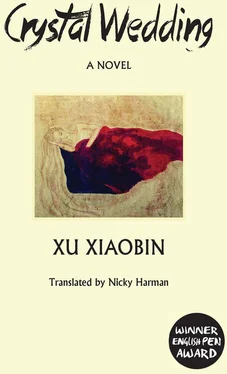

Xiaobin Xu - Crystal Wedding

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Xiaobin Xu - Crystal Wedding» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2016, Издательство: Balestier Press, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Crystal Wedding

- Автор:

- Издательство:Balestier Press

- Жанр:

- Год:2016

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Crystal Wedding: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Crystal Wedding»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Crystal Wedding — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Crystal Wedding», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

When Tianyi did the reading, next day, the results confirmed this even more clearly. The trigrams told her: In autumn the tiger’s coat is gorgeous and it is a favourable time to wade the great river. Exactly what her dream had said. So Tianyi called Tianyue and told her: ‘You can go. This autumn.’

By the middle of August, Tianyue had still not received her acceptance from the college. This was unusual and Tianyue had almost given up hope, but Tianyi encouraged her: ‘You will go, just be patient.’ ‘Of course I will, but not this time, right?’ said Tianyue. ‘No, it will be this time,’ Tianyi insisted.

One day at the end of August, Tianyue finally received her letter. The envelope contained a brief apology too, saying that they had written the address wrong and the letter had been returned undelivered, and they had had to re-send it, and so on and so forth. The first thing Tianyue did was to phone Tianyi. ‘You got it absolutely right, Sis!’ she exclaimed.

16

Qing left Beijing at about the same time as Tianyue. She did not seem happy to be going. ‘Tianyi, I’ll never forget how good you were to me,’ she said. ‘But I just don’t know why Zheng’s Mum took against me. I never asked for anything except just a word from Zheng and I would have waited for him, I would have waited thirteen years, but I didn’t get a single word. I reckon that his parents never said anything to him about me. What do you think, Tianyi?’

Tianyi slowly shook her head. To be honest, she did not know why Zheng’s parents had been so cold to Qing, either. Was it that they just didn’t like her? Even if they didn’t, they must see that Qing had travelled all the way from South China to Beijing for him, and deserved a little courtesy and warmth. As these thoughts passed through her head, Tianyi tried to comfort her: ‘Don’t think like that, there’s probably a lot more going on than you imagine. You know he’s still married to Yiyi, even if they don’t have feelings for each other. His parents have fallen out with her, but she is still legally his wife. Even his Mum and Dad can’t do anything about that. And they’re old, they might even be worried that a divorce would be messy. After all, they’re getting on in years, and things upset them. If Yiyi made a fuss, it would be terrible for them, wouldn’t it?’

Qing was silent for a long time. Then she said: ‘I don’t agree with you, Tianyi. You see, his mother…she just doesn’t like me. It’s true. She doesn’t like anything I do. If I touch something in their house, she looks like thunder. She won’t even let me wash the bowls, it’s as if I’ll bring the family bad luck by touching them.’

Tianyi could not help bursting into giggles. Oh my god, she thought, mothers- and daughters-in-law …!’

‘What are you laughing at, Tianyi?

‘Just at the way you described it. That’s enough, girl, you go off and live a good life and if I ever see him one day, I’ll speak up for you.’

Tears streamed down Qing’s face as she said goodbye. She would miss her friend and mentor so much. She had been like an older sister to her. When would she ever find someone like her again?

But Tianyi was no saint. True, she had done something most women would not have done, made a huge effort and taken her former boyfriend’s girlfriend under her wing, but deep down she was not happy about it. Perhaps that was when her feelings of closeness to Zheng began gradually to fade. A man as attractive as Zheng was always going to have countless girls openly in love with him, or pining in secret. But Tianyi was a proud woman and she had no intention of being yet another of his admirers. She would rather be a true friend in his hour of need. She remembered when she was a young girl reading Balzac’s La Cousine Bette . One bit had made a particular impression on her: Lisbeth quotes the Old Testament story where the rich man has whole flocks but ‘the poor relation has one ewe-lamb which is all her joy.’ She preferred to be that one ewe-lamb.

Tianyi dreamed of being loved deeply by one man, a man that she loved and that she was not competing with anyone else over. But this seemed impossible in a society where every individual, particularly someone who stood out for some reason, was surrounded by crowds of others. Unless they were on a desert island, of course, or in prison, as was the case right now. She thought that when Zheng came out of prison would be the time to break with him. She could imagine the number of young women who would descend on him when he came out. But she would turn and leave without allowing herself to look back, like the mermaid who saved the prince. Unless … unless her prince cast off everyone else and came in pursuit of her, and asked her to marry him.

Qing had no sooner left than Lian returned. Someone called from his work to tell her that he would be back that night, around two o’clock in the morning Beijing time. The office bus would arrive at half past ten. Tianyi got Niuniu ready, took thick jackets for them both and set off. On the bus, Lian’s colleagues kept asking: ‘Niuniu, have you been missing your daddy?’ But Niuniu refused to open his mouth.

Tianyi knew what her son was thinking: Why has he come back so quickly? Her cherubic little boy, plump as a doll, had been jealous of his father from when he was tiny. It was not just that he used start crying if he touched his father’s moustache in bed at night. It went much further. ‘Wait till I’m grown up and I’ll mince Dad up into meat pancakes and take a chunk out of him.’ That was the kind of thing that came out of this sweet kid’s mouth.

Tianyi found it funny. She really had no idea when this animosity between father and son had started. Lian was strict with Niuniu, that was true, but he adored his son. Tianyi tried to redress the balance by telling the boy: ‘Daddy loves you. Daddy’s put much more time and effort into looking after you …’ But Niuniu turned a deaf ear.

It was the early hours, past three o’clock, before Lian walked through the Nothing to Declare channel and Niuniu had been sound asleep for some time. Tianyi, leaning on the barrier, stared as he emerged clad in denim jacket and jeans. The outfit really did not suit him, he just looked awkward. As he wove his way through the crowd towards her, she saw that the sun had burned his round face much darker than usual. Is this really my husband? She wondered. So much picking and choosing and this is who I ended up with.

Yet he still felt like family, even though he was ugly, awkward, dull, wrong in all sorts of ways, compared to all the handsome guys she used to go out with. For years to come, she would have conflicting feelings about Lian: she felt close to him but uncomfortable with him at the same time. It was an odd feeling. If they were apart, she quickly forgot even what he looked like. Then she saw him again, and there was no one but him.

He really was her family. Jetlag had not yet caught up with him, and when they arrived home they sat up talking until daybreak. He had brought her a complete set of Italian gold jewellery, had spent several hundred dollars on his purchase. He told her about his colleagues’ astonished reaction. She could believe it. This was the early 1990s, and very few people like them, educated but not wealthy, could afford stuff like this. Suddenly her spirits lifted a little. No matter what, I still come first for Lian, she thought. Even his beloved son is only getting a Gameboy. But a few days later, something happened that astonished her.

Peng brought a guest over, and not just any old guest either. Tianyi recognized him instantly; he was one of Zheng’s closest friends, Tong. A short man with a broad forehead, he bore a striking resemblance to Bukharin in the film, Lenin in 1918 . She had nicknamed him Bukharin and he had laughed and acknowledged it. He seemed a good-tempered sort — only a very few friends knew he was prone to terrifying explosions of rage. He had been convicted of assaulting his ex-wife and scarring her face for life, but he did not serve a sentence because his wife refused to press charges. The wife told her parents from her hospital bed: ‘Don’t cause trouble for him. He’s a good man.’

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Crystal Wedding»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Crystal Wedding» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Crystal Wedding» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.