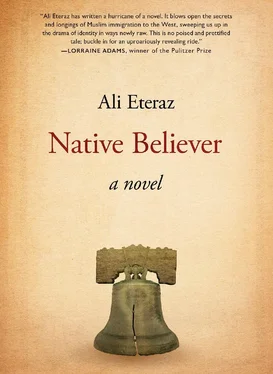

Ali Eteraz - Native Believer

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Ali Eteraz - Native Believer» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2016, Издательство: Akashic Books, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Native Believer

- Автор:

- Издательство:Akashic Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2016

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

Native Believer: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Native Believer»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

stands as an important contribution to American literary culture: a book quite unlike any I've read in recent memory, which uses its characters to explore questions vital to our continuing national discourse around Islam."

—

, Editors' Choice

"M.'s life spins out of control after his boss discovers a Qur'an in M.'s house during a party, in this wickedly funny Philadelphia picaresque about a secular Muslim's identity crisis in a country waging a never-ending war on terror."

— "[A] poignant and profoundly funny first novel….Eteraz combines masterful storytelling with intelligent commentary to create a nuanced work of social and political art."

— "Eteraz's narrative is witty and unpredictable…and the darkly comic ending is pleasingly macabre. As for M., in this identity-obsessed dandy, Eteraz has created a perfect protagonist for the times. A provocative and very funny exploration of Muslim identity in America today."

— "In bitingly funny prose, first novelist Eteraz sums up the pain and contradictions of an American not wanting to be categorized; the ending is a bang-up surprise."

— "Who wants to be Muslim in post-9/11 America? Many of the characters in Ali Eteraz‘s new novel

have no choice in the matter; they deal in a variety of ways with issues of belonging and identity in a society bent on categorizing, stereotyping, and targeting Muslims."

— "Ali Eteraz’s fiction has encompassed everything from the surreal and fantastical to the urgently political.

, his debut novel, explores questions of nationality, religion, and the fears and paranoia in American society circa right now.

— Included in John Madera's list of Most Anticipated Small Press Books of 2016 at "Ali Eteraz has written a hurricane of a novel. It blows open the secrets and longings of Muslim immigration to the West, sweeping us up in the drama of identity in ways newly raw. This is no poised and prettified tale; buckle in for a uproariously messy and revealing ride."

—

, author of "Merciless, intellectually lacerating, and brutally funny,

is not merely a Gonzo panorama of Muslim America-it's one of the most incisive novels I've ever read on America itself. Eteraz paints our empire with the same erotic longing and black, depraved wit that Nabokov used sixty years ago in

. But whereas Nabokov's work was set in the heyday of America's cheerful upswing, Eteraz sets the country in the new, fractious world order. Here, sex, money, and violence all stake their claims on treacherously shifting identities-and neither love nor god is an escape."

—

, author of Ali Eteraz's much-anticipated debut novel is the story of M., a supportive husband, adventureless dandy, lapsed believer, and second-generation immigrant who wants nothing more than to host parties and bring children into the world as full-fledged Americans. As M.'s life gradually fragments around him-a wife with a chronic illness; a best friend stricken with grief; a boss jeopardizing a respectable career-M. spins out into the pulsating underbelly of Philadelphia, where he encounters others grappling with fallout from the War on Terror. Among the pornographers and converts to Islam, punks and wrestlers, M. confronts his existential degradation and the life of a second-class citizen.

Darkly comic, provocative, and insightful,

is a startling vision of the contemporary American experience and the human capacity to shape identity and belonging at all costs.

![Анастасия Быкова - Believer [СИ]](/books/424458/anastasiya-bykova-believer-si-thumb.webp)