— What in the hell is that thing? he said.

Creasie was standing there staring at it, something about her of the bereaved.

— Nothing but an old nigger dummy, Mr. Finus. What everybody done forgot about but me.

HE SKIPPED THE council meeting that evening, sat at the kitchen table and sipped from a bourbon and water, and looked at the blackened heart inside the jar he’d set down beside his glass. He wasn’t hungry after the plate of food out at Birdie’s.

After staring at the telephone a while, he picked it up, called the press that printed the Comet , and told them not to run Birdie’s obituary.

— Just pull it, he said. -I’ll run it next week.

He took his drink into the living room, thought about turning on the television for late-night crap and decided not to. Mike shambled creakily in and humphed himself to the floor at his feet with a wheeze. About midnight he woke up with his neck in a crick from leaning it back on the sofa in sleep. Mike snored gently on the floor. He sat there awhile working his neck with his fingers, feeling tired to the marrow and last drop of old blood. Then he got up slowly, careful not to wake old Mike, and went down the stairs to the street and got into his pickup. He laid the jar from Creasie’s house on the seat beside him and drove through town past the orphans’ home and turned in at the cemetery, lights off, around to where he knew Earl Urquhart’s grave was.

Wasn’t hard to find, with the earth in a mound over Birdie’s fresh grave. The air was cooler, though there was little breeze. Finus took the jar and walked over to the graves, not sure what he intended to do. But there lying beside Birdie’s grave was a shovel, apparently left there by one of the gravediggers.

He read the stone. Earl Leroy Urquhart, 1899–1955.

— Well, old Earl, Finus said, I don’t mean this as a desecration. Just a restoration, of sorts. If it’s just an old pig’s foot, I’m sorry, no disrespect intended.

He took the shovel and made four neat incisions in the turf at what he figured about chest level for the body of Earl down deep, and lifted it carefully and set it aside. Then he dug enough earth out to place the jar a foot or so deep in the hole. He replaced the dirt, packing it down with the sole of his Red Wing, leveled it, then knelt and placed the piece of turf back on top of it, pressing it and shaping it until as best he could tell the surgery wouldn’t be too obvious.

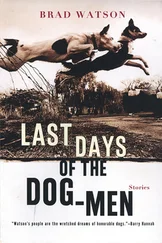

He stood up, brushed his hands off on his pants, knocked the dirt off his boots with the shovel, and laid the shovel back down next to the mound of Birdie’s earth where he’d found it. Stood there catching his breath. For the first time in his life he seemed to feel every one of his true and earthly years. Maybe it’s coming my time, he thought, where my time here and the way I feel about it have come together and will take me out of this light and into another, or eternal darkness. He figured he could take it either way, wouldn’t make much difference to the man he was here and now. That would be that and then, not this and now. He looked about. Down behind him in the area where he had used to park and rut with Merry Urquhart now there were neat lines of headstones just as there were in every other part of the cemetery, the place was about filled up. He looked up. The night was clear, and the nearly full moon he hadn’t noticed but had worked by stood high above the magnolia trees at the cemetery’s summit, between Finus and the dim penumbra of the lights in town. He heard something and saw it moving toward him along the narrow paved pathway from the street. Some kind of dog trotting along, veered away from him and through the stones between him and the magnolias and stopped there when it saw him watching it. It stood stock still, sideways, head turned his way, to see what he was going to do.

Finus stood stock still, too. It looked just like the dog in his death dream, the one he’d told Birdie about, charged with guarding his body while he slept. Though it was clear the dog didn’t know him and feared him. A guilty, negligent dog.

— Hey! Finus called to it. The dog twitched but didn’t run. Both stood still watching the other. Then after a minute or so the dog seemed to relax. He looked away from Finus, looked around the cemetery, feigning a casual manner, sniffed the grass at his feet, as if something interesting there had caught his attention for a second. It was a transparent attempt to look innocent. He looked back at Finus, as if Finus had said something else. He hadn’t. Then the dog trotted on his way, weaving around headstones, crossed the gravel path at the crest of the hill and disappeared over it down into the lower parts of the cemetery out of sight. Finus watched him go. His heart was racing. When it calmed he looked around at where he was, at Birdie’s grave, at Earl’s stone, at the other stones shining dully in the moonlight, at his truck waiting stunned or suspended, incomplete without him.

HE SLEPT TILL two o’clock the next afternoon, took his time rousing, and went into the office at four, and finished rewriting her obituary early that evening. He took out the addendum about the poisoning, and inserted three new bulleted items:

She was the best at making a little gumball out of sweet-gum sap of anyone yours truly has ever known.

She developed later in life the ability to suck in her cheeks and make her lips into a funny little narrow pucker, made her look like a little mouse nibbling something, real comical, made all the children laugh.

She once at age eighty speared an actual mouse using one of those sticks with a nail in the end of it, used for picking up paper trash, disgusted that everyone else had been too squeamish.

He put the copy in Lovie’s basket, then put his overnight bag in the truck and helped Mike get up into the passenger seat. He filled the tank at the Shell station on the highway just south of town, then headed up the long hill that was the south ridge and rolled along the general decline to the Gulf coast.

It was a route he’d known since a small boy, though the roads had changed, improved. His grandfather accompanied them to the fort at the end of the peninsula, down on the Alabama Gulf coast, for dinner with the Commandant. His grandfather knew the Commandant, from the Spanish-American War. They ate by flickering lantern and candle light. Out the open, screened window, gentle summer waves flopped and crushed on the sand. Finus sat quietly as after dinner the grown-ups drank from small bowled glasses and his father and the Commandant smoked cigars that his grandfather leaned over and whispered to him came from Cuba.

— Go to the south window, Finus, and see if you can see the lights of Cuba.

He’d smirked at his grandfather, who knew he was too smart for that. His grandfather was big and open-faced, a bald and friendly giant, and his touch was gentle on Finus’s shoulders and on his back, and when he tousled Finus’s light brown hair. His parents were dressed in their best clothes, though he could not see his mother, she was eternally just at the edge of his eye. He was in his worsted wool suit, and the Commandant wore his dress jacket with the high collar and stars. The Commandant was a bachelor and had hired a Creole cook whose head at what seemed regular intervals appeared from behind the swinging door to the kitchen to look at him with oddly green eyes in her coppery face, and then disappeared again. The food was wonderful, fish in a sack, gumbo, fried grouper, bright white scallions like pearls with long green stalks, and boiled new potatoes so small and sweet they didn’t even need butter. The Commandant gave him a very small measure of red wine. The others raised their glasses to him, love and admiration in their eyes.

Читать дальше