“Of course, I did. What are you saying? I spoke with Mrs. Thomas. But they’re giving you another chance. You are being suspended, not expelled. So I’d say they were being fairly generous. They could kick you out, you know, altogether.” She hesitated. She hated to go there — Edward would say it was none of their business. He’d say everyone had to take responsibility for his or her own actions. “Robbie didn’t also get into trouble?”

Jamie’s face fell shut. “Robbie wasn’t part of it. It was just me and Rian.”

“Who’s Ryan?”

He stuck his lip out. “You’re busy.” He flopped back on his bed and folded his hands on his chest.

She knew that sullen face, the hands closed up like an oyster. Whoever Ryan was, and why Ryan was involved rather than Robbie, his lab partner — Jamie wasn’t now going to explain, not until he was ready. Jamie was like the shower they had in that first home in London. Sometimes the water would suddenly turn cold, sometimes hot, sometimes the pressure would disappear altogether. You had to be ready to jump in and out accordingly. She shook her head. “I want you to stay in your room until I tell you that you may come out. I’m going to see Mathilde about fixing you something. Did you see her?”

Jamie shook his head. “I said I’m not hungry,” he repeated. “I bought two Camembert sandwiches at the airport. I ate them on the bus.”

Her heart swelled up against her rib cage. He knew how to take the airport bus by himself; he bought himself stale sandwiches wrapped in paper. He would have been sitting there, in the same city as she, without her even knowing it, chewing on his baguette, his heart a mix of joy at being back home and dread over being in trouble at school. Maybe dread also at having to face his parents — at having to face her. Jamie. However bad what he’d done was, he’d done it just out of desperation. He didn’t want to disappoint them. “Okay.”

“Don’t go bugging Mathilde,” he said and raised an eyebrow. “If you know what’s good for you.”

“That’s enough.” She would not laugh. “You just sit tight.”

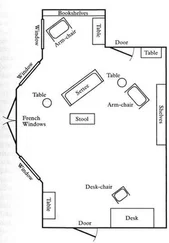

She shut his door behind her and made her way back down the hall. The door to the study was closed. She could hear the clip of Edward’s voice behind it but muffled by the heavy wood of the door such that she couldn’t make out what he was saying. This was not the first time she’d faced this same scene, a closed door, the sound of her husband’s voice on the phone behind it in midday. She shook the thought from her mind. If something terrible had happened somewhere, she probably would have heard it from Patricia Blum. Bad news spread faster than a virus amongst the expat community in Paris.

“Did you speak with the minister?” she asked Amélie as she passed through the dining room into the kitchen. She couldn’t go in there while he was on the phone, talking.

“Excuse me, Madame. The ministre goes to ze study and closes ze door. Clac! I do no speak with him.”

The harder she worked at it, the worse poor Amélie’s English seemed to be becoming. Clare tugged on her hair. If something had happened, surely Edward would have looked for her before closing himself into the study. At the very least, he would have asked her whereabouts from Amélie.

She noticed a bit of dust on the back of a chair but resisted the urge to flick it. Amélie might take it as a reproach. “Well, let’s go see about the plates,” she said.

The men had brought the crates all in by now and opened them.

“Votre signature, Madame, s’il vous plaît,” one of the men said, handing her a clipboard.

She signed her name at the bottom, added the date, and handed it back to him. She took one last look around the dining room while Amélie showed them out. Their dining room might not be the Salon Bleu of the ambassador’s residence, but rich with polished wood and sparkling crystal it did look attractive. With Amélie no longer watching, she removed that one tiny piece of dust. Then she followed the deliverymen’s path through to the kitchen. As she passed the pantry, she could see the wines in their wooden boxes. She hoped Amélie had thought to check the contents against the order sheet, but she refrained from asking. Amélie didn’t usually make mistakes, other than grammatical ones. Amélie, for example, would intuit she shouldn’t mention Jamie’s return to Edward. Clare couldn’t count on Mathilde for the same sort of discretion. But maybe Mathilde hadn’t seen that Jamie had come in.

The cook was standing beside the kitchen table, a huge bowl pushed up against her abdomen, a whisk the length of a donkey’s tail in her hand. Clare could smell freshly sliced onion, mint, and basil; Mathilde must have already prepared the sauce for the potatoes. For one sweet second, she was swept back outside, into the spring, into the light.

“Well, Mrs. Moorhouse, the minister is home à midi and a bit early at that, n’est-ce-pas? ” Mathilde commented, without stopping her flaying of the pale yellow yolks in the bowl. “And now I suppose you’ll be needing a lunch for him, and me trying to make a miracle out of these here eggs. They’re a right waste of good money, they are, these eggs. He’s no good, ce marchand. ”

The image of Jamie, alone in the airport, buying sandwiches, came to her. As much as the idea disturbed her, she couldn’t help but think he’d done well to get them. She wouldn’t want to ask Mathilde to prepare a lunch for him now, and Mathilde probably wouldn’t accept anyone else mucking about in the kitchen. Mathilde was in a creative fury. “That’s all right, Mathilde, I’ll find something for Mr. Moorhouse.”

“Oh, and be leaving the minister with a cold sandwich at lunch? Anyhow, I can’t have anyone fussing about in my kitchen right now.”

Clare smiled; Mathilde was as consistent as a toothache. Knowing her so well gave Clare a curious sense of satisfaction.

Then she remembered the closed door to the study.

“Did the minister come to speak with you when he came in? I mean, he didn’t come to say anything about having to cancel?”

“Cancel!” Mathilde dropped the whisk. “ Ça va pas ça! First you announce we’ll be putting on a V.I.P. dinner on one day’s notice, and a night off for me, too, then you add to it just hours before without telling me, then you want to take everyone away! Were you planning to tell me that after I finished preparing dinner? And me already with the dessert half done and the bread rising?”

“No, no, no,” Clare reassured her, inwardly scolding herself. If something serious had happened, something that might demand cancelation, like another bombing in London, Edward would have called her before he even got home. And he wouldn’t have been the one to tell Mathilde about it. Dealing with staff was her job.

Where was her phone? She reached into her sweater pocket — but her BlackBerry was still in her purse. She hadn’t used it while she was out, although she almost had, to call the embassy to find a ride back from the airport tomorrow for Jamie. Wasn’t she glad now that she hadn’t! How embarrassing if word had gotten round that James was already in Paris when she’d called: the minister’s wife didn’t even know in which country her younger son was. Still, it was odd she hadn’t received any calls. Had she neglected to switch it back on after Edward’s welcoming speech at last night’s reception? Maybe Jamie had tried to call her on her cell phone to ask permission to leave, to fly to Paris. Unable to reach her, he wouldn’t have tried the home phone, because he’d have had to call when his dad was still home in order to catch that morning flight. It didn’t make anything okay, but it did explain things a little.

Читать дальше