She was twenty years old, and the summer seemed to drag as heavily on her limbs as the heat wave. The summer internship she’d been so happy to land at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston had turned out to be hours of cataloging in an office with a small window and even smaller fan, and sometimes the days felt so heavy and still, she could hardly bear it. Even the green of her aunt’s suburban lawn when she returned in the evenings provided no relief.

“Which one?” Tools lay sprawled out across the drive. She spotted at least three wrenches, each slightly different.

“Fuck if I know,” Kevin had said. “That one.”

She picked up the one Kevin had indicated, trying to ignore the stranger as well, but his eyes bore into her. She let her hair fall over the wrench and stole a glance, not towards his face but at the rest of him: he had on threadbare corduroy pants that seemed impossibly heavy for a day this hot. The skin of his knees, visible through the worn cloth and almost at her eye level, was white as birch. He looked unlike anyone she knew, not least because of the blunt way he was examining her.

Kevin grunted and threw the wrench back at her. She had to hop to one side to avoid being hit. “Too big. Give me another.”

“You aren’t going to get nowhere like that,” the stranger said, after she’d handed over the second wrench. His voice was soft but not gentle. He jumped down from the wall, and using one booted foot — despite the heat, he was wearing leather boots — kicked the remaining wrench towards Kevin. “You need that one, you stupid feck,” he tossed over his shoulder, sauntering towards Aunt El’s kitchen. The door slammed shut behind him.

Clare sat down on the wall where he had been. “Who was that?”

“Aw, fuck. Him? Some cousin. Some ten-times-removed fucking cousin. One of my mom’s charity cases.”

She tried not to cringe. Aunt Elaine had had her move in with them in Newton after seeing the dank, cramped room Clare had planned to rent for the summer in downtown Boston, not far from the museum. Aunt Elaine had a big heart for everyone.

Kevin reached out for the final wrench, the one the ten-times-removed cousin had kicked, and applied it to the gasket. Oil came rushing out. He cursed and grabbed for a bucket. “Motherfucker!”

She got up and went into the kitchen.

And there he was, seated in the kitchen alcove, one hand clasped around a glass bottle of Coke. A film of condensation had developed around its neck, and water sweated down its sides. He flicked a few drops from his fingers and lifted the bottle to his mouth.

She sat down beside him on the bench and watched his Adam’s apple as he drank. He was barely older than she was, maybe twenty-one or twenty-two. He wasn’t taller either. They were shoulder to shoulder at the table, and she could feel his exposed knee beside hers. The smooth heat of his skin penetrated through the stupor of the summer, through her lanky, indolent limbs. She had to move her leg.

He drained the contents of the bottle in one go, set it back on the table, and belched. Then he looked at her. She looked down at her hands. He looked at them also.

She raised her head. Their eyes met, and she saw that his were very light blue, and as cool and glittering as winter. Despite how they’d burned into her earlier, there was nothing sunny about them.

“I’m Clare.”

“I know who you are.” Niall reached out and lifted one of her hands. He turned it over carefully before setting it back down on the table.

“You surely have beautiful hands, Clare.”

She’d unfolded her hands in front of him. One by one, her fingers; long, thin, pale. The gentle lift around her first knuckle and slender knob of the second knuckle, the soft mound of the third, and then the broad, flat, pearly nails, fingers longer than the palm, tapering only slightly, graceful without appearing fragile. First her thumb, then her index finger, then her middle finger, her ring finger, her pinkie. They stripped for him without having worn clothing.

“Thank you,” she said.

The heat had gotten to her. The heat, and she’d been too hot to eat breakfast that day. It had weighed down on her, drowning her better judgment, had drowned it that whole long hot summer. She wiped her brow and realized she’d been clutching Patricia’s arm.

“Heavens,” she said, loosening her scarf.

There was no Niall here, just row after row of tins and cardboard boxes and rounds of cheese and bundles of asparagus. Still, she had so thought she’d seen him this time for real, and then she had grabbed Patricia Blum’s arm. She didn’t even like Patricia Blum. She stepped back from her.

“Hey, that’s okay!” Patricia patted her. “I’ve been there. Hot flashes?”

“No, no, nothing like that. It’s just…Oh, too much to do today.” She smiled and tried to erase her foolishness. She was barely forty-five. Hot flashes? Did she seem older to Patricia? “Please pass along greetings to Em on Jamie’s behalf. It was lovely to chat.”

She pushed off from Patricia, like a canoe from a dock, backwards, wobbly but sliding, trying to hide her embarrassment. The false sightings had begun the first time she and Edward lived in London, continuing after they were subsequently posted to Paris. Not all the time, but in random flurries — months would go by, even a year, then for a few weeks she’d be sure she saw him almost daily. They’d subsided when she and Edward had been moved back to Washington and had remained dormant upon their ensuing return to Paris, and she’d thought finally she was done with thinking she saw Niall in a crowd when she was just seeing another pale blue-eyed man disappearing into a sea of people. Now, lately, they had returned to her. And, like today’s, they’d become so real.

The problem was Ireland. Just the thought of moving there and already she was losing her grip.

She lifted her shopping basket sternly and, in the aisle devoted to imported British foods, collected all the boxes of oatcakes on the shelf. As she waited by the checkout, she tried not to peer around her, tried not to use her height to glance over the heads of the others. She busied herself instead by verifying the expiration date on the biscuits. The point was to stop struggling with regret. Niall would never seek her out. Niall couldn’t seek her out. His body had been lowered in a casket into the moist earth of Derry the November after she met him. Niall was long dead and buried.

She reached the courtyard of the Residence, basket of cheese and asparagus hanging over one arm, homeopathic drops for Mathilde tucked away next to the to-do list in her sweater pocket, just as the men delivering the official plate and silver crested with Her Majesty’s royal emblem from the embassy pulled up. She checked her watch: 11:45 a.m. Too late to call Barrow before lunch.

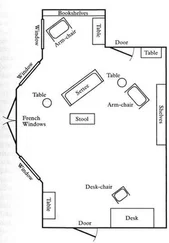

She nodded and slipped past the men, into the building’s downstairs foyer. Outside, the sun was still shining, the wind still light and playful, but upstairs would soon be the table settings to unpack and lay out, and she was going to make sure that was done correctly. Her determination to make this dinner right had started to feel almost religious, like an act of penance. They were in the first decade of the third millennium, nearly three thousand people had been killed on one day alone in New York City by lunatics, some forty thousand civilians had since died in Iraq, more were dying daily, maybe right at this very moment, due to a war begun by British and American politicians, a war that neither she nor Edward (although he took care, like any good British foreign diplomat, never to promote his own political leanings) supported but that had affected their personal lives to the degree that they’d felt compelled to exile their younger son, and she was fixating on silverware. She couldn’t be stopped for directions by an innocent stranger on the street without scanning for escape routes — she did wonder what had happened to that man, if he’d found his doctor, and if so, if the doctor had managed to help him; he’d looked so ill — but aligning china plates was her mantra. And there was her youngest son, imploding at school, and she’d had to put off speaking with the headmaster. It sounded ridiculous. But upholding standards was part of Edward’s job, and she believed in Edward. Edward furthered the cause of civility. He would not bring anger to Dublin if he got the top post there. He would bring discussion. So she would let the building’s door swing shut behind her, closing out the breeze and sunshine as well as the disorder and chaos of the external world, and train her thoughts to tableware and wineglasses.

Читать дальше