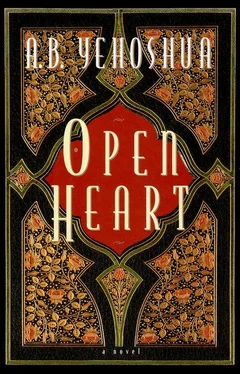

A. B. Yehoshua

Open Heart

To Gideon, who returned from India

Set thy heart upon thy work

But never on its reward.

Work not for a reward;

But never cease to do thy work.

— The Bhagavadgita, Chapter 2, verse 47 (Translated by Juan Mascaro, Penguin Classics, 1962)

Part One. Falling in Love

The incision was ready for stitching now. The anesthetist slipped the mask impatiently from his face, and as if the big respirator with its changing, flickering numbers were no longer enough for him, he stood up, gently took the still hand to feel the living pulse, smiled affectionately at the naked sleeping woman, and winked at me. But I ignored his wink, because my eyes were fixed on Professor Hishin, to see if he would finish the suturing himself or ask one of us to take over. I felt a tremor in my heart. I knew I was going to be passed over again, and my rival, the second resident, was going to be given the job. With a pang I watched the movements of the scrub nurse as she wiped away the last drops of blood from the long straight cut gaping in the woman’s stomach. I could have scored an easy success, I thought bitterly, by completing the operation with a really elegant suture. But it didn’t look as if Hishin was about to hand over the job to anyone. Even though he had been at work for three straight hours, he now rummaged, with the same supreme concentration with which he had begun the operation, through the pile of needles to find what he wanted. Finally he found the right needle and returned it angrily to the nurse to be sterilized again. Did he really owe it to this woman to sew her up with his own hands? Or perhaps there had been some under-the-table payment? I withdrew a little from the operating table, consoling myself with the thought that this time I had been spared humiliation at least, even though the other resident, who had also apparently grasped the surgeon’s intention to perform the suturing himself, maintained his alert stance beside the open abdomen.

At this point there was a stir next to the big door, and a curly mane of gray hair together with an excitedly waving hand appeared at one of the portholes. The anesthetist recognized the man and hurried to open the door. But now, having invaded the wing without a doctor’s gown or mask, the man seemed at least to hesitate before entering the operating room itself and called out from the doorway in a lively, confident voice, “Haven’t you finished yet?” The surgeon glanced over his shoulder, gave him a friendly wave, and said, “I’ll be with you in a minute.” He bent over the operating table again, but after a few minutes stopped and started looking around. His eyes met mine, and he seemed about to say something to me, but then the scrub nurse, who always knew how to read her master’s mind, sensed his hesitation and said softly but firmly, “There’s no problem, Professor Hishin, Dr. Vardi can finish up.” The surgeon immediately nodded in agreement, handed the needle to the resident standing next to him, and issued final instructions to the nurses. He pulled off his mask with a vigorous movement, held out his hands to the young nurse, who removed his gloves, and before disappearing from the room repeated, “If there are any problems, I’ll be with Lazar in administration.”

I turned to the operating table, choking back my anger and envy so that they wouldn’t burst out in a look or gesture. That’s it then, I thought in despair. If the women are on his side too, there’s no doubt which of us will be chosen to stay on in the department and which will have to begin wandering from hospital to hospital looking for a job at the end of the month. This is clearly the end of my career in the surgical department. But I took up my position calmly next to my colleague, who had already exchanged the needle Hishin handed him for another one; I was ready to share in the responsibility for the last stage of the operation, watching the incision close rapidly under his strong, dexterous fingers. If the incision had been in my hands, I would have tried to suture it more neatly, not to mar by so much as a millimeter the original contours of the pale female stomach, which suddenly aroused a profound compassion in me. And already the anesthestist Dr. Nakash, was getting ready for the “landing,” as he called it, preparing to take out the tubes, removing the infusion needle from the vein, humming merrily and keeping a constant watch on the surgeon’s hands, waiting for permission to return the patient to normal breathing. Still absorbed in the insult to me, I felt the touch of a light hand. A young nurse who had quietly entered the room told me in a whisper that the head of the department was waiting for me in Lazar’s office. “Now?” I hesitated. And the other resident, who had overheard the whisper, urged me, “Go, go, don’t worry, I’ll finish up here myself.”

Without removing my mask, I hurried out of the shining darkness of the operating room and past the laughter of the doctors and nurses in the tearoom, released the press-button of the big door sealing off the wing, and emerged into the waiting room, which was bathed in afternoon sunlight. When I stopped to take off my mask, a young man and an elderly woman immediately recognized and approached me. “How is she? How is she?”

“She’s fine.” I smiled. “The operation’s over, they’ll bring her out soon.”

“But how is she? How is she?” they persisted. “She’s fine,” I said. “Don’t worry, she’s been born again.” I myself was surprised by the phrase — the operation hadn’t been at all dangerous — and I turned away from them and continued on my way, still in my pale green bloodstained surgical gown, the mask hanging around my neck, the cap on my head, rustling the sterile plastic shoe covers. Catching the stares following me here and there, I went up in the elevator to the big lobby and turned into the administrative wing, where I had never been invited before, and finally gave my name to one of the secretaries. She inquired in a friendly way as to my preferences in coffee and led me through an imposing empty conference lounge into a large, curtained, and very uninstitutionally furnished room — a sofa and armchairs, well-tended plants in big pots. The head of the department, Professor Hishin, was lounging in one of the armchairs, going through some papers. He gave me a quick, friendly smile and said to the hospital director, who was standing next to him, “Here he is, the ideal man for you.”

Mr. Lazar shook my hand firmly and very warmly and introduced himself, while Hishin gave me encouraging looks, ignoring the wounding way he had slighted me previously and hinting to me discreetly to take off my cap and remove the plastic covers from my shoes. “The operation’s over,” he said in his faint Hungarian accent, his eyes twinkling with that tireless irony of his, “and even you can rest now.” As I removed the plastic covers and crammed the cap into my pocket, Hishin began telling Lazar the story of my life, with which he was quite familiar, to my surprise. Mr. Lazar continued examining me with burning eyes, as if his fate depended on me. Finally, Hishin finished by saying, “Even though he’s dressed as a surgeon, don’t make any mistake, he’s first and foremost an excellent internist. That’s his real strength, and the only reason he insists on remaining in our department is because he believes, completely wrongly, that what lies at the pinnacle of medicine is a butcher’s knife.” As he spoke he waved an imaginary knife in his hand and cut off his head. Then he gave a friendly laugh — as if to soften the final blow he had just delivered to my future in the surgical department — reached out his hand, placed it on my knee, and asked gently, in a tone of unprecedented intimacy, “Have you ever been to India?”

Читать дальше