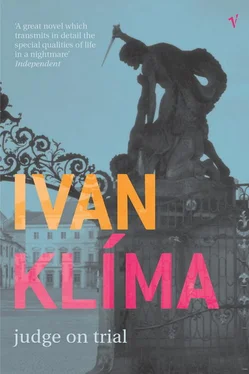

Ivan Klíma - Judge On Trial

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Ivan Klíma - Judge On Trial» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1994, Издательство: Vintage, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Judge On Trial

- Автор:

- Издательство:Vintage

- Жанр:

- Год:1994

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Judge On Trial: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Judge On Trial»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Judge On Trial — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Judge On Trial», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The next day I started my new job. I was assigned a desk in an office whose occupant was announced on the doorplate as Dr Oldřich Ruml.

Accustomed to the strict routine in The Hole, I arrived at work at the same time as the secretaries. I unpacked my things and set them out on the desk top and then started to study the titles of the books on the bookshelf while listening attentively to the noises from the corridor (compared with my old corridor, the silence here was uncanny and even depressing), and then the phone rang. I lifted the receiver with suspense-filled expectation, even though the call couldn’t possibly be for me. A woman’s voice asked the whereabouts of Dr Ruml. (I was astonished to be addressed as ‘sir’, a form of address never used in The Hole.) The phone rang several more times. Men’s and women’s voices asking for a man I had never met in my life, asking for more precise details of where he might be and when I was expecting him to arrive. Towards noon he finally appeared, a well-built fellow with a thick mop of short blond hair. He flung a parcel of journals on to the desk, thereby indicating he belonged there. He wore an immaculately cut suit (including a waistcoat, which I considered snobbishly old-fashioned), and his tie was transfixed by a tie-pin in the shape of a snake. He declared that they had already told him about me and was sure we would get on like Castor and Pollux. He listened to my account of telephone calls and personal callers and explained to me that I would have to learn to spend as little time as possible in those premises or I’d never get anything done. Then he asked me several discreet questions in an effort to ascertain to which clique or power group I belonged, to whom I owed my appointment, who my powerful protector was, and what my immediate ambitions were. He must have concluded I really was entirely uninformed in such matters (or artfully pretending to be) and declared that he would have to clue me up without delay or I’d be bound to commit irreparable gaffes.

His speciality was economic law, but he was far more interested in politics, or what went under that name here and which in reality consisted entirely of intrigues and scarcely visible movements and shifts within the ruling circles. He classified his colleagues into influential, promising and insignificant. With people in the first two categories his aim was to maintain good relations and he therefore spent his time attending a plethora of meetings, consultations, social evenings and seminars, where his interest was never the subject under discussion but who was taking part.

I never fully understood what place in his hierarchy I could have occupied, nor how I came to be promoted to be his virtual protégé. Could he have overestimated the importance of my family connections and mistakenly placed me among the influential? Or was it that he needed someone who could help him sort out his ideas and in front of whom he could rehearse his power games? Or maybe he simply took a liking to me, and out of a need to have someone like-minded and also useless around (he had lots of acquaintances but no real friends) decided that I would do?

He used to invite me to his parties — which he called garden-parties (and indeed they did take place in the garden when the weather was fine) — even though I was in no position to pay him back in kind.

He had just got married. His wife didn’t attract me. She seemed to me like a child who had grown up too soon and was trying to conceal the immaturity of her features under layers of face powder. I never knew what I could, or should, talk to her about. On one occasion, I arrived at a party some time before the other guests and we were compelled to spend several minutes together. She was probably making a conscientious attempt at conversation. She asked me whether I was interested in pictures and brought me a book about abstract painting, and then proceeded to tell me something about Chagall and Miró. I told her truthfully that I had little interest in art. At that moment I noticed something incongruously unshapely about her slender, girlish figure and asked her whether she was expecting a baby. In three months’ time, she said, and expressed surprise at my ignorance; Oldřich had told her I knew. Then the other guests started arriving, interrupting a conversation which was not to resume until many years later.

2

The more I studied, the more I realised the inadequacy of my previous education. I did not have the faintest notion about real sociology or real political science, had never penetrated any of the foreign legal systems and possessed a knowledge of jurisprudence so biased as to be non-existent. Half a century of modern thinking had remained concealed from me. Philosophers and lawyers whose names were familiar to grammar-school children elsewhere in the world were utterly unknown to me. I had not even mastered a single foreign language. As I began to realise the extent of my ignorance I started to panic. Would I ever manage to make up for all those wasted years?

Sometimes I got carried away, mostly to the detriment of my work. I started to study sociology and logic. I discovered that I lacked the fundamentals of maths and statistics and bought myself several text-books which I started on, but abandoned as soon as they demanded more time and concentration than I could afford to give them, having decided in the meantime to improve my English. There was a growing pile of unread journals, scholarly reports and new books on my desk. And I had seen nothing of modern art and not been to an exhibition of any kind for years. I bought myself a transistor radio and had it on while I was studying (if only Magdalena could have seen me) and used it to deafen my restive spirit. Sometimes I was overcome with a sense of the futility of all my efforts. Knowledge was meaningless of itself: I needed to link it to some goal, to some living person. I wrote to Magdalena telling her I was missing her, but received no reply.

My brother gave me a tennis racquet for my birthday. The accompanying comment was that he could not stand to watch me getting fat and turning into a misery. We used to go twice a week, weather permitting, always early in the morning, to bumpy tennis courts situated terrace fashion under the windows of the institute where he worked. It could be that I showed a certain aptitude for the game since we were soon well-matched opponents. Occasionally, he would bring some of his mathematician colleagues with him and, even more often, female colleagues and friends — who were not required to understand mathematics or even play tennis — and we would form mixed doubles. After our match we would drink cheap lemonade, though my brother’s female colleagues were happy to accept an invitation to something better and rather stronger. But I was always in a rush to get back to my institute and anyway they didn’t appeal to me — I lacked Hanuš’s free-and-easy way of enjoying himself, not to mention his apparent gifts for making love.

At the beginning of spring, our institute played host to a visitor from London University with the Scots name of Patrick MacKellar. He was my age and specialised in juvenile delinquency, a subject I was assigned to at the time. They therefore decided that I should act as a guide for our visitor. I was quite unsuited to such a role. What I knew of Prague was two or three wine bars and a couple of churches, apart of course from a comprehensive grasp of the Old Town street plan. At a pinch I could have put together a programme for two or three evenings, but my charge was due to spend a whole month in Prague. In order to fill the time, I invited him on a trip to the town where I had spent the other part of my childhood. On a sunny Sunday morning we boarded a bus and set off in the direction of Litoměřice.

Oddly enough, I did not feel I knew the landscape, and even the fortress town itself seemed unfamiliar. (I had not been there since the day my cousin came for us in the gas-powered lorry.) I walked through the straight lanes with my guest and pointlessly drew his attention to the long out-of-date names on the barracks and tried unsuccessfully to find something that recalled the atmosphere of those years. We set off along the road in the direction of the Small Fortress where we joined a group of tourists. They were Jews in dark clothes and black hats. In schoolgirl English — though faultless, as far as I could tell — their guide endeavoured to acquaint them with events that she herself must have been too young to remember. We accompanied them up to the museum as well. And here you can see pictures from the neighbouring ghetto (yes, that was it, at last I recognised what I had been in) where most of the people died. One hundred to one hundred and fifty victims every day. Each person had a maximum floor space of one and a half square metres and the people had to work ninety hours a week, and that included children from fourteen years of age.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Judge On Trial»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Judge On Trial» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Judge On Trial» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.

![Юрий Семецкий - Poor men's judge [СИ]](/books/413740/yurij-semeckij-poor-men-s-judge-si-thumb.webp)