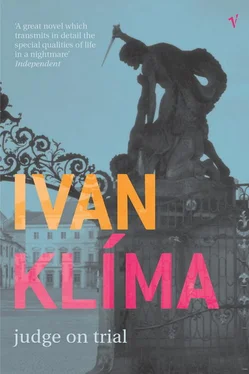

Ivan Klíma - Judge On Trial

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Ivan Klíma - Judge On Trial» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1994, Издательство: Vintage, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Judge On Trial

- Автор:

- Издательство:Vintage

- Жанр:

- Год:1994

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Judge On Trial: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Judge On Trial»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Judge On Trial — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Judge On Trial», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

‘I couldn’t. I just couldn’t. You were there.’

‘I would have left if you’d told me it bothered you.’ He could still smell gas. He bent over the cooker and sniffed the burners.

‘I could-n’t,’ she repeated. ‘I couldn’t have told you to go if you were al-rea-dy there.’

‘Have you been drinking?’

‘I don’t know. I expect I had some tea. And some-thing else before that. But that’s ages ago. I called you but you weren’t home.’ She was still unable to open her eyes and spoke as if speaking to him from a dream. Her voice was hoarse.

‘Did you turn the gas on?’

‘It wasn’t me. He turned it on.’

Her words made no sense to him. She had clearly been drinking. He assumed she had been getting drunk somewhere and come home late for that reason.

‘I turned it off afterwards,’ she said.

She looked so wretched and helpless that he suddenly felt sorry for her. ‘You ought to go and lie down.’

‘I can’t! I’ve got to go — you know — to the library.’

She didn’t seem to him capable of any activity at all. ‘Give them a call to excuse yourself. Tell them you’re going to the doctor’s.’

‘But I’m not going to the doctor’s.’

He took the milk out of the refrigerator and poured some into a saucepan.

‘Where have you been these past two days, Adam?’

He put the pan on the stove. He hesitated a moment before striking a match. ‘But I told you where I was going, didn’t I? You oughtn’t to go to work. I’ll call them myself if you like.’

‘Were you there with her?’

He turned away. Yes, of course he was there with her. Why did she have to ask? After all she hadn’t been drinking on her own, either.

‘Why don’t you answer, Adam?’

But there was something wrong with her; something had happened that was troubling her. What point was there in hurting her even more? ‘No,’ he said.

‘You weren’t there with her?’

‘No!’

‘You were there on your own?’

‘Who was I supposed to be with?’ Shame overwhelmed him. He was lying brazenly like a false witness.

‘You’re not lying to me, are you, Adam?’

‘No!’ He took a loaf of staleish bread out of the bread-bin and cut some slices, trying to make them as thin as possible.

He buttered the bread and topped each slice with a round of salami and some tomato. ‘I have to go and wake the children,’ he said. ‘Or do you want to wake them yourself?’

She made no move, so he put the plate on the table. As he passed her he noticed that the odd smell of gas was coming from her. It was in her hair and her clothes. He bent over her. ‘Did you try to gas yourself?’

‘No, he did it,’ she said. ‘Adam! Oh, Adam!’ she sobbed.

He straightened up again. He knew he ought to comfort her in some way. Or to speak to her tenderly. And indeed for a moment he was gripped by an agonising sympathy and searched for the right word. He could also have hugged her or stroked her acrid hair.

But at the same time a paralysing feeling of disgust started to well up in him. Something about her disgusted him. He couldn’t tell whether it was the senselessness of what she had done or the other person with whom she had obviously done it. Or maybe just the vile stench of gas.

‘I have to go and wake the children,’ was all he said. ‘They’ll be late for school otherwise.’

2

He left the house with the children. He had made Alena leave the kitchen before they came in for their breakfast. She had gone to the bedroom promising to sleep it off. He had promised to excuse her at work. And to be home soon. He had not promised to ‘talk it all over’ although she had begged him to insistently. He accompanied the children to the end of the block. They ran off immediately after saying goodbye. His daughter was wearing a short brown coat and her hair flew about her head as she ran, while the little chap’s bag leaped up and down on his back.

At their age he hadn’t gone to school. That was not exactly true: he’d attended for the first two years. Then the authorities had banned him from going. Anyway he couldn’t recall having mixed with his peers back in those days or played with them. His childhood peers had been the ones who ended up in the gas chamber. That fact occluded anything that had happened earlier.

What if Alena was to try to gas herself again?

It was not a good idea to leave her on her own. He turned and hurried back home. Someone had just gone up in the lift but he was still capable of beating the lift up to the second floor. He reached there at the moment two men were getting out of the lift. They glanced quickly along the passage and then came over to him. After reading the name on the door they asked: ‘Are you Dr Kindl?’ They didn’t even have to show their passes. He knew all too well who they were.

‘Yes, that’s me.’

‘We have something we would like to ask you.’

‘Well?’ He was unable to contain his agitation. ‘Would you like to come inside?’

‘We would sooner you came along with us for a moment. After all, you’ve no hearing right now.’

He shrugged.

‘Were you just on your way home?’

‘I was coming back for something I’d forgotten.’

‘You may go and fetch it.’ One of the men stood in the doorway, preventing him from closing the door. They did not enter the flat, however.

Alena was lying half-clothed on the couch, covered with a green blanket, her face thrust into the pillow. She was asleep. He wrote her a note: If I’m slightly delayed, don’t worry. He couldn’t concentrate. He added: Never do anything like that again!

The grey Volga saloon was parked round the corner, which explained why he’d not noticed it on his way back. They sat him in the back between the two of them and didn’t utter a word the whole way. The car pulled up eventually in the narrow lane off Národní Avenue.

They passed the porter’s lodge and took the lift up to the second floor. Then they proceeded down a long corridor until, at last, they opened one of the many doors and entered. At a desk sat a man with a broad, puffy face. The man stood up. It was impossible to tell his age but he was certainly the elder of them. ‘I could caution you, but I don’t think it will be necessary in your case.’

‘I agree. But I would like to know for what reason I was summoned.’

‘You were invited here for an informative chat.’

‘Surely there was no need for it to have assumed such dramatic form.’

The man brushed his remark aside. ‘So you are a judge. Since when?’

‘I hardly think that is the subject of your enquiry.’

‘Were you in America, Dr Kindl?’

‘Why do you ask? You gave me the passport.’

‘You know very well we do not issue passports here. During your stay in America you didn’t work as a judge, did you?’

‘Certainly not. That was out of the question.’

‘Did you have a lot of friends in America?’

‘No.’

‘Do you correspond with them frequently?’

‘Any correspondence is solely about personal matters.’

‘In the course of your professional duties have you ever come across criminal activity that might qualify as incitement through the dissemination of subversive literature?’

‘Not as far as I recall. Certainly not in the recent period.’

‘What is your attitude to such criminal activity?’

‘The same as to any other criminal activity.’

‘Which is?’

‘You don’t intend to cross-examine me, surely.’

‘Have you been receiving such literature from abroad?’

‘No!’

‘You didn’t even try to get it sent to you?’

‘No.’

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Judge On Trial»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Judge On Trial» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Judge On Trial» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.

![Юрий Семецкий - Poor men's judge [СИ]](/books/413740/yurij-semeckij-poor-men-s-judge-si-thumb.webp)