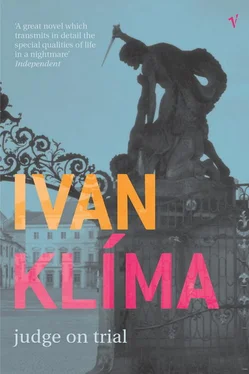

Ivan Klíma - Judge On Trial

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Ivan Klíma - Judge On Trial» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1994, Издательство: Vintage, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Judge On Trial

- Автор:

- Издательство:Vintage

- Жанр:

- Год:1994

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Judge On Trial: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Judge On Trial»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Judge On Trial — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Judge On Trial», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

I waited curiously to see whether someone would draw any conclusions as to his suitability. But his behaviour, if news of it ever got out at all, did not seem to perturb any of our superiors.

He always wanted us impose the stiffest penalties the law allowed, since the longer the criminals and enemies were behind bars the better it would be for society as a whole. This was so contrary to the spirit of even those laws we were supposed to be upholding that I actually managed to protest on several occasions, but he either didn’t listen to me or didn’t understand.

My only colleague, Dr Klement Horváth, had served there for many years. He was an experienced lawyer, having graduated from the rigorous imperial schools, and an expert in Roman, Austrian and Hungarian law. He had been a judge during the first and second republics and the independent Slovak state. Having once tried those who were now in power, all the more willing was he now to try those who used to be in power then. He toed the line; not a word, not a glance suggested that he conformed unwillingly, or that he thought anything but what he was supposed to think.

I felt morally superior. I hadn’t had to change my views, fall into line or turn my coat. I was able to act according to my convictions.

I acted according to my convictions, fought for the new system of justice, defended the nascent new order. I served it with every ounce of my strength. I delivered dozens of verdicts (the Presiding Judge enrolled us in competition: the more cases the individual judge dealt with, the better the assessment), sat on various commissions and committees, and travelled round the villages, cajoling, negotiating and educating.

Occasionally, however, I would be overcome with nostalgia for my far-off home, besides having a permanent sense of not being appreciated. It was out of the question that I, who was destined to achieve something of importance, if not indeed of great significance, should spend the rest of my days in such a godforsaken spot.

I used to write lots of letters in those days (to my parents, uncles, colleagues and even Professor Lyon) with enthusiastic accounts of my selfless achievements, while occasionally complaining — as if jokingly — about my banishment, from which it looked as if only someone’s intercession could release me.

I received comforting replies, written — as I increasingly realised — in another world, and packages from my mother containing carefully wrapped plum slices or pastries filled with ground poppy seeds (goodness knows where she obtained them).

In the course of time, my home drifted further and further away from me, and with it all my former and current notions about the world. My ideals and university precepts started to quake from the moment I opened my eyes in the morning. How much longer would they survive the life here?

My favourite person in the courthouse was our clerk, Vasil. He was born locally and was the same age as my father — though, unlike him, he was a powerful man with enormous hands and a broad head on which there was always perched some hat or fur cap. He knew — or made a convincing show of knowing — the backgrounds of all the litigious individuals. He could remember all the sentences passed since the end of the war when he first came to work for the court.

He used to come and see me in my office, a knapsack thrown over his shoulder. He would always have a short chat with me if no more, regaling me with sayings about people, the weather and the ways of the world. From time to time, and especially in winter when it was already getting dark, he would pull a bottle of home-made spirits from his knapsack, pour us both a nip and reminisce about pre-war days before they had a court, a hospital or a factory, when he used to earn money as a forestry labourer or from smuggling cloth into Poland and alcohol out. If he had a good few drinks he would start to talk about the independent state, when he was set to catch smugglers instead, as they appointed him to the local constabulary. And if he got really drunk he would tell me the most fantastic stories claiming that they had really happened: about the mysterious black dog which always appeared behind the cottage belonging to an uncle of his who had inexplicably disappeared, about the golden coach and four which appeared to his father when he was returning from a social. The horses were driven by an eyeless coachman with hair aflame. He was the blind count who had once owned the local estate, and whom God had struck blind during his lifetime as a punishment for his dissolute behaviour. But even blindness did not secure his repentance and he went on to kill his coachman out of spite. So after his death he had been punished thus. That was justice. I was not sure what his intentions were in telling me that story, or whether he believed it or not. He also expounded his own theory about how society was ordered. The world was made up of those who ruled and those who worked. The masters were always changing, however. When new masters came along they would make all sorts of promises to their subjects so as to win them over, but as time went by they would forget about their promises so nothing changed, only the masters. The poor had to work and the only chance they had of getting anything was by cheating the gentry, and it was the people’s God-given right to cheat their masters. That was the way things had always been. And that was the way they would be now, he said, when I tried to explain to him that it was the people, not the masters, who were ruling now. The people couldn’t rule, he told me, because from the moment they were in power they were no longer the people but gentry. Meanwhile those who were ruled and had to do the work were the people, even if they had once been gentry, and the new people would cheat and rob the new masters. And they would get punished for it.

He was the only person I could turn to for advice (not counting those who volunteered advice themselves) and I’m sure I wasn’t the only one to quiz him, that both the Presiding Judge and Dr Horváth secretly consulted him too. For Vasil knew in advance the effect which the verdict would have both in town and in the defendant’s home village, how many children the defendant was really supporting and how big and influential his family was. Vasil alone knew how to explain the true motives of crimes, instead of the fictitious ones derived from the literature: not class hatred but ancestral hatred, unhappy loves, inherited jealousies and unpaid debts.

It was only just before I left The Hole that I discovered he accepted bribes from the parties involved in return for intercession on their behalf, and that much of what he had told me, and which I had taken as gospel, was the product of his imagination. In his eyes, I was one of the new gentry (or at least one of their servants) and it was his God-given right to do me down.

That autumn, they assigned me my first politically significant case: that of a former shopkeeper from the village of Vyšná. I was supposed to convict him of concealing (like the majority of the shopkeepers whose shops were confiscated) some of his stock. In cash terms the concealed portion amounted to four thousand five hundred crowns.

I still failed to grasp the logic of a legal system which, knowing that it couldn’t prosecute everyone who broke the new laws, selected certain individuals and punished them severely as an example to the rest. I was amazed that the prosecutor ascribed to the shopkeeper’s action, which was so understandable, a deliberate intention to jeopardise supply, and in aggravating circumstances to boot. (Those aggravating circumstances were the defendant’s origins and the continuing political tension in the region.) What did the prosecutor expect of me? What sort of penalty for a hidden sack of sugar, several bottles of spirits, a few enamelled cooking pots and some axes? Five years? Six years? Or ten, even?

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Judge On Trial»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Judge On Trial» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Judge On Trial» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.

![Юрий Семецкий - Poor men's judge [СИ]](/books/413740/yurij-semeckij-poor-men-s-judge-si-thumb.webp)