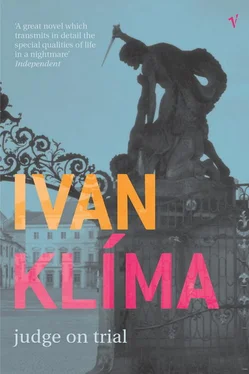

Ivan Klíma - Judge On Trial

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Ivan Klíma - Judge On Trial» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1994, Издательство: Vintage, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Judge On Trial

- Автор:

- Издательство:Vintage

- Жанр:

- Год:1994

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Judge On Trial: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Judge On Trial»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Judge On Trial — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Judge On Trial», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

‘Open the window, would you, so we can breathe. And take off that jacket, for heaven’s sake.’ She poured the wine into the glasses. ‘Or are you in a hurry?’

He wasn’t going anywhere in a hurry. He leaned out of the window. In the backyard two fellows were bashing a sheet of tin while coloured rags blew about above their heads.

‘You can sit on the chair or the armchair, or stretch out on the settee.’ She slipped off her shoes and sat down on a corner of the settee with her legs crossed beneath her. ‘It’s a nice place, isn’t it? It’d be a pity to lose it.’ She lit a cigarette. ‘When I was a little girl we lived in the country — near Cáslav. Dad was the local policeman. When the comrades took everything over in February ’48, he shot himself. But he made a bad job of it and just shot a hole in his lungs, and then went through the most terrible suffering for the next three years till he died. Then we moved here. Different fellows would move in from time to time, but Mum would always kick them out again in the end. One of them had studied to be a priest and he always used to tell me the kinkiest stories about the saints: fantastic horror stories. He also carved me a great big nativity with really weird figures. All the animals had human heads. They’re still in a box up in the loft. Another one of them was a railwayman, he used to spend his evenings at home making locomotives out of wooden skewers and coloured paper. I slept in the kitchen and I was desperate for somewhere to put my paints and paper and a bit of space for myself, but there were his models everywhere. But they were pretty good, and I even helped him paint some of them. He used to bring me loads of paper and gave me a box of Pelican oil pastels. I can’t think how he came by them; I expect he pinched them. In the end they arrested him along with a gang of fellows who were stealing from railway wagons. We chucked all his models into a box, but I packed them in wood shavings first so they wouldn’t get squashed, otherwise he’d be sad when he came for them. He didn’t come for them anyway; he kicked the bucket inside. It wasn’t you who sent him down by any chance, was it?’

‘What was his name?’

‘Well now you ask me, I can’t remember. We used to call him Joey. After he landed up inside, Mum didn’t have any other lodgers. But then she started going out with some gent. I never set eyes on him as he never came here. He must have been well heeled, because he used to buy Mum lovely clothes. He was probably married and could only manage to see her once a week and then she would come home after midnight. She was so regular I could even invite my David here every Wednesday evening. He was two years above me in school and used to make fantastic sculptures, with long bodies like he had himself. He also used to make some real weird things from old sheets of tin. He would paint them with car enamel and other sorts of paint and then fire them. They had a kiln at home because his dad was a blacksmith. Once he got dreadfully burnt and spent almost a month in hospital. He said that if ever he decided to end his life, he’d jump in a furnace. But he didn’t burn himself to death, that was left for someone else.’

He tried to concentrate on what she was saying but it was impossible: her presence distracted him. Why had she invited him here? Why was she confiding in him? ‘How old were you at the time?’

She reflected for a moment. ‘I must have been at least fifteen. And one of my teachers was in love with me too. He was always terrified in case someone saw us. When he first came here, he was shaking all over because he’d bumped into some woman on the way in. He always had to get drunk first. Then he used to tell me all about how he fought in a foreign army, how his wife took all his money, and also about his beautiful daughter who was the only reason why he couldn’t leave his family, otherwise he would have married me. I never understood why he said it because I naturally had no desire to marry him. He assured me I had talent and would go far with it. I just enjoyed painting: daubing on paint. In those days I hadn’t the faintest idea colours had numbers, or that one day I’d be issued with an industrial-sized bottle of pink to do five hundred dogs’ muzzles. I thought it was so fantastic that in a world where everything was precisely regulated and planned, I could paint what I wanted. Trees growing roots upwards, for instance. Or a girl walking naked along the street with everyone enjoying it and no one going after her, because in my world there’s no such thing as police.’

‘You’d like to walk along the street naked?’

‘Why not, if I felt like it? I remember once we got terribly drunk and climbed out on the roof and stripped off. We were still at school. I bet you wouldn’t like that, would you?’

‘I don’t know, but I’ve never run about a roof naked in my life.’

‘That’s a pity; you might have turned out differently.’

‘Do you think it would have improved me?’

‘You’d have started to relax a bit and not think so much about your paragraphs all the time.’

‘I don’t think about them at all, except when I really have to.’

‘Who are you kidding? You’re always thinking about what you ought to be doing, or not doing. Right now you’re thinking about whether it’s right for you to be sitting here listening to this crap I’m spouting. Have a drink, at least!’ She pushed the glass towards him. ‘I like people who jump off a bridge, say, just because they feel like it. And I can’t stand people who have to weigh it all up beforehand and then live accordingly. Like Ruml, for instance.’

‘Your criteria are a bit one-sided.’

‘You’re bound to think that way. Or you wouldn’t be in that job you’re in.’

‘There’s nothing particularly bad about what I do, is there?’

‘You don’t think so? You can’t see anything dreadful about helping them sustain their disgusting system? Doesn’t it turn your stomach?’

An unexpected note of anger suddenly entered her voice, or of personal interest, more likely. He didn’t know she had some experience of the courts. But what did he know about her?

‘Ruml told me they put you in prison when you were small, and it was something I liked about you, the fact you’d been through something — unlike him, who used to get taken to school by car. But I just couldn’t fathom out how you could then go and send some other poor devil to a lousy, dirty hole somewhere.’

‘That was different, though, wasn’t it?’

‘What? Just because they weren’t children? Or because you didn’t get sent down with them this time?’

‘Why are you getting so hot under the collar? All over the world they have laws, and someone has to try people under them.’

‘All over the world they have laws that say it’s a crime to want to live like people and not slaves? That’s news to me. And why should it be you who does it?’

‘And what should I do, according to you?’

‘Something that would allow you to be free.’

‘Not everyone can be an artist. We’d all die of hunger.’

‘We’ll die anyway.’

‘It’s too late, I don’t know how to do anything else.’

‘Maybe you’re wrong; maybe you just haven’t hit on it yet. You could be a rabbi, for instance,’ she suggested. ‘No, I don’t mean a rabbi, I mean the one who does the singing. I happened to be by the synagogue not long ago and there was a fellow there with a big nose just like yours and he sang so wonderfully he mesmerised me. Afterwards I caught sight of him outside chatting to some girl and she was completely knocked out by him too. Or you could be a mendicant friar. You could wander around the villages in the Bohemian Forest preaching to the people. I bet you’d enjoy that — preaching. They’d give you bread and wine in return and a place to sleep for the night. And you would creep into some girl’s bed, have a fantastic time and the next morning you’d be gone with the wind. You could be a sailor, outward bound from Hong Kong to Honolulu, and there’d be beautiful native girls waiting for you everywhere.’

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Judge On Trial»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Judge On Trial» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Judge On Trial» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.

![Юрий Семецкий - Poor men's judge [СИ]](/books/413740/yurij-semeckij-poor-men-s-judge-si-thumb.webp)