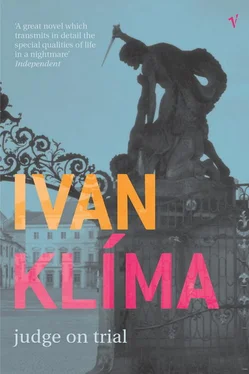

Ivan Klíma - Judge On Trial

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Ivan Klíma - Judge On Trial» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1994, Издательство: Vintage, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Judge On Trial

- Автор:

- Издательство:Vintage

- Жанр:

- Год:1994

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Judge On Trial: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Judge On Trial»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Judge On Trial — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Judge On Trial», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

‘Listen,’ he’d clearly not been listening to anything she had said, ‘you oughtn’t to sit there like that. You look tired to me. You should come to bed.’

She roused herself: ‘You haven’t asked what I went as.’

‘Well, sorry, but it does happen to be half past two in the morning.’

‘You wouldn’t ask me even if it was noon!’

‘So what did you go as?’

‘A snowflake,’ and she realised immediately how silly it sounded. At any rate to someone who’d never wanted to go to a fancy dress ball in his life.

‘And were you a success?’

‘I don’t know! Success,’ she repeated, ‘why do you measure everything by success?’ She stood up and went off to the kitchen. The water running into the washing-up bowl at two thirty in the morning didn’t murmur but roar; her ears rang.

He came after her. ‘Leave the washing-up, for goodness sake!’

‘I can’t stand it staying here overnight.’

‘I’ll wash it,’ he offered. ‘I’ll see to it in the morning.’

‘Would you really?’

The roar of the water ceased. She put her head on his shoulder. ‘Do you love me?’

When she finally got to bed, she hesitated a moment, but then snuggled up to him as she had done almost every evening for ten years already. At that moment she was overcome with a blissful sense of security and belonging.

‘It’s gone three, already,’ he said reproachfully as if the passage of time were her responsibility. He tried to cuddle her.

‘Wait a sec,’ she told him, ‘couldn’t you open the window? It’s very smoky from next door.’

‘The window is open.’

‘Wider, then!’

He got up and opened both windows fully.

‘And he had an awful life, you know,’ she said suddenly.

‘Who?’

‘The one I was telling you about.’

‘Who were you telling me about?’

‘Honza. They sent his dad to prison. You know, when they were gaoling everybody.’

‘My father went to prison too.’

‘But you were older. He was only six when it happened.’

‘Oh, yes?’ he said without interest. ‘Shouldn’t we get some sleep?’

‘Why do you always talk about sleep when I’m trying to tell you something?’

‘It’s just that it’s about time. I have a hearing in the morning and you ought to be packing. The children are looking forward to getting away.’

‘We didn’t sleep either. We hardly slept at all the past two nights.’

‘Precisely!’

‘I can’t help it. I’m always so het up. I can never get to sleep.’

‘So tell me how it was with his father.’

‘Honza was terribly attached to him,’ she said gratefully. ‘The whole time his father was in prison he thought about him and dreamed about him as the best person in the world. But when his father came back after eight years, things looked quite different. But don’t you want to get to sleep?’

‘Not any more. Talk away.’

‘They’d done something to his father; broken him somehow. He came back full of bitterness, hating his wife and Honza. He used to beat him and humiliate him.’

‘How do you know?’

‘He told me about it.’

‘Maybe he wasn’t being impartial. People are incapable of telling the truth about themselves.’

‘But that’s how it felt to him. He was only thirteen by then. It completely broke him up. He skipped on his school work and started getting into mischief, fighting and breaking windows. It was all to try and get his father’s attention. But instead, his father stopped talking to him. Just imagine, more than two years without a single word. He pretended not to see him. They’d be sitting together in the same room but his father would behave as if he was alone. When he was dying and Honza came to visit him in hospital, he didn’t speak to him. Honza went home and tried to commit suicide. He slashed his wrists: I’ve seen the scars.’

‘You shouldn’t think about it. You’re too worked up.’

‘And do you love me?’

‘You know I love you.’

‘I love you too.’ She might have cuddled him if she had had enough strength left.

The next day she didn’t wake until eleven thirty. She found a note on a chair at her bedside: ‘The children are at your mother’s. Get some sleep. The washing-up’s done! You can give me a call. Have a good sleep.’

Again no expressions of affection. It was his way of punishing her for having been so tired yesterday and because he’d done the washing-up.

It annoyed him that she was usually tired, even though she didn’t have a full-time job. As if six hours in the library, as if travelling to and fro in a packed tramcar weren’t enough in themselves to drain her of energy. As if in addition she didn’t look after him and the children. In the old days women didn’t have to go to work and they’d have a maid to help them as well. So of course they could be sprightly whenever their husbands remembered them.

She got up and went to the kitchen. Her head ached and her limbs felt weak. This was the start of her holiday. He could have written: I love you. Or added some kisses. But he had done the washing-up, even though he’d left the sink dirty and she would need to wash half the plates again. And he’d taken the children to her mother’s, got up early and done things surprisingly quietly, not even woken her up.

She had a drink of milk (he’d done some shopping too). Her eyes smarted so much she had to keep blinking. She climbed back into bed and draped a scarf over her face. Next day she was leaving, she realised; she would be alone with the children in the hills. What if he came after her? But she was known there, her brother would be there with his family. It didn’t bear thinking about.

What did bear thinking about then? What was there to look forward to? There weren’t even any nice books being published, and it was her job to withdraw the nice ones that had come out before from circulation. It was such a humiliating task. Maruš had been thrown out so she was ashamed to go and see her because she herself had not yet been sacked. She had had only two friends in the library and they had both fled abroad. She didn’t even know where they were now. What was left for her?

When she was six years old, during the last year of the war, everyone expected Prague would be bombed and her parents had sent her to an auntie in the uplands on the Moravian border. The auntie wasn’t a real relation — she had been in service with her parents before she got married. She had a cottage with tiny windows, and the kitchen, which smelt of bread and buttermilk and boiled potatoes, was hung with coloured prints: the Virgin Mary and Child, St Anne with the Mother of God, a Guardian Angel. Her auntie had taught her a prayer — the only one she had ever said in her life. She could remember the way it ended: people may love me or hate me, but I shall not neglect Thee, and shall pray for my enemies, and commend their spirits and mine own into Thy hands. On Sunday she would go with her aunt to church where the portly priest in his robe would say mass. When they met him on the way out after mass he would hold out his pudgy hand to her smelling of incense and she would have to touch it with her lips. In those days she made up her own picture of God. He sat in the middle of a white cloud on a rocking chair (like the one her father sat in when he came home from work), clutching a crosier tight in His hand, and smiling with toothless gums. (She couldn’t explain why, but the idea of God having teeth seemed undignified to her.) He was tall, even massive (reminding her of His Majesty the King of Brobdingnag from the illustration in the children’s edition of Gulliver’s Travels ), and invisible. Even so, she had no trouble seeing Him clearly: each evening, the moment she whispered ‘their spirits and mine own into Thy hands’, He would sail out all-powerful on His shining white cloud, motionless and smiling toothlessly, high above her head, and she would be overwhelmed with a sense of security such as she had possibly never known since.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Judge On Trial»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Judge On Trial» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Judge On Trial» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.

![Юрий Семецкий - Poor men's judge [СИ]](/books/413740/yurij-semeckij-poor-men-s-judge-si-thumb.webp)