Forrest Leo

The Gentleman

To

Dad,

who’d have been proud,

and

Frank M. Robinson,

who taught me how

EDITOR’S NOTE. I have been charged with editing these pages and seeing them through to publication, but I do not like the task. I wish it on record that I think it better they had been burned.

— Hubert Lancaster, Esq

In one great gulp I drank my tea and gazed

Upon the grim and gloomy world anew—

And gasped at how my griping eye had lied.

The rain still fell, the wind still blew, but now

I thought it grand! I love the rain!

Not rain nor cloud did cloud my eye—‘twas thirst!

— LIONEL LUPUS SAVAGE, from ‘The Epiphany’*

One In Which I Find Myself Destitute & Rectify Matters in a Drastic Way

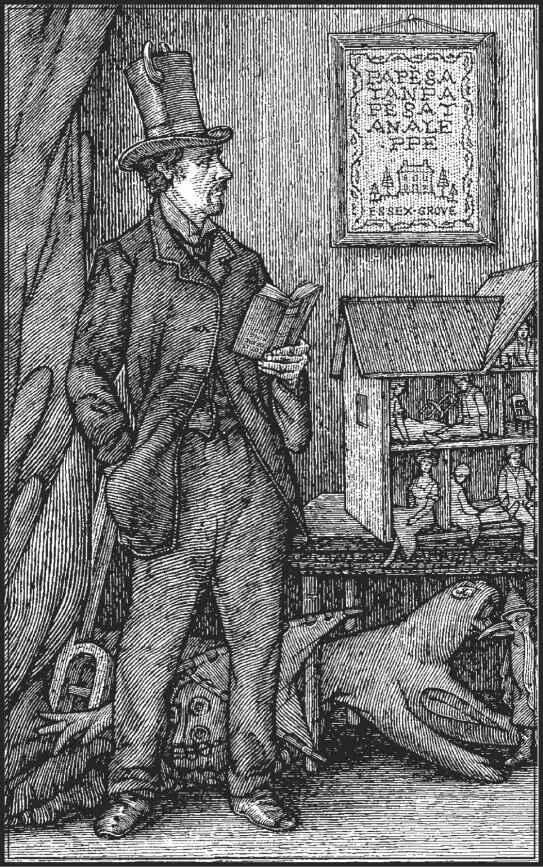

My name is Lionel Savage, I am twenty-two years old, I am a poet, and I do not love my wife. I loved her once, not without cause — but I do not anymore. She is a vapid, timid, querulous creature, and I find after six months of married life that my position has become quite intolerable and I am resolved upon killing myself.

Here is how my plight came about.

Once upon a time about a year ago, I was very young and foolish, and Simmons informed me we hadn’t any money left. (Simmons is our butler.)

‘Simmons,’ I had said, ‘I would like to buy a boat so that I can sail the seven seas.’

I hadn’t, I suppose, any real notion of actually sailing the seven seas — I am not an adventurous soul, and would relinquish my comfortable seat by the fire only with reluctance. But it seemed a romantic thing to own a boat in which one could sail the seven seas, should one suddenly discover he had a mind to.

But Simmons (whose hair is grey like a thunderhead) said with some remonstrance, ‘I’m afraid you cannot afford a boat, sir.’

‘I can’t afford it? Nonsense, Simmons, a boat cannot cost much.’

‘Even if it cost next to nothing, sir, you still could not afford it.’

My heart sank. ‘Do you mean to tell me, Simmons, that we haven’t any money left?’

‘I’m afraid not, sir.’

‘Where on earth has it gone?’

‘I don’t mean to be critical, sir, but you tend toward profligacy.’

‘Nonsense, Simmons. I don’t buy anything except books. You cannot possibly tell me I’ve squandered my fortune upon books.’

‘Squander is not the word I would have used, sir. But it was the books that did it, I believe.’

Well, there it was. We were paupers. Such is the fate of the upper classes in this modern world. I didn’t know what to do, and I dreaded telling Lizzie — she was in boarding school at the time, but even from a distance she can be quite fearsome. (Lizzie is my sister. She is sixteen.) Despite the popularity of my poetry, I was not making enough money at it to maintain our household at Pocklington Place. Another source of income was necessary.

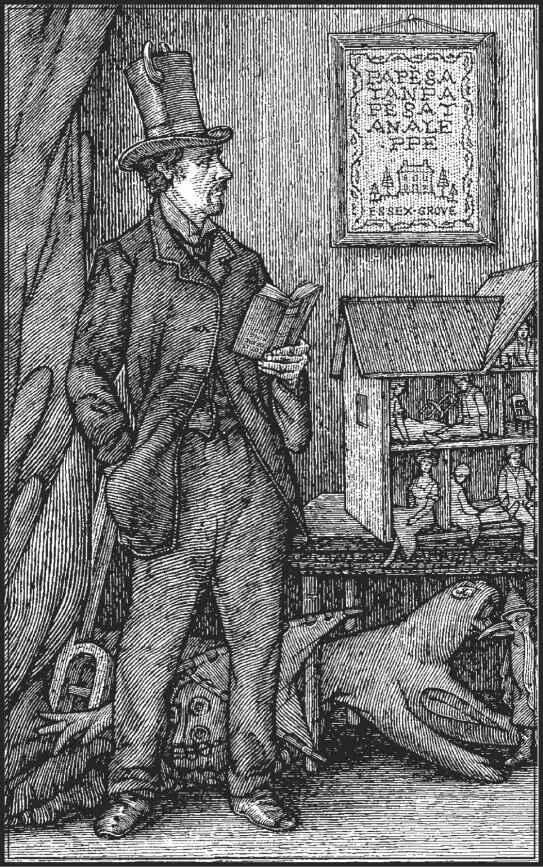

I set out to find one. Being a gentleman,* the trades were quite out of the question. Commerce is not a gentlemanly pursuit and sounds wretched besides. I considered physic or law, but lawyers turn my stomach and physicians are scoundrels all. I decided it must be marriage.

Finding a suitable family to marry oneself off to might sound a bore, but turned out to be rather a lark. I sought out only families of enormous means, without bothering myself too much about social position. As such, I had a few truly unpleasant experiences — but no dull ones.

The Babingtons were every bit as eccentric as one reads in the papers and proved entirely unsuitable. (Not that I object to eccentricity; but it is not a quality one searches for in a wife.) Sir Francis Babington and I are old friends, he having once savaged* a collection of my poetry.

‘Frank,’ I said one evening, having contrived to run into him while taking a turn about the Park,* ‘I suppose it’s about time I came over for dinner.’ (I abhor taking turns about the Park. I only do so when I have ulterior motives.)

‘Looking for a wife, Savage?’ said he.

‘Certainly not,’ I replied coldly. I was thrown off. I had not thought myself so transparent. I groped for a new subject but was not quick enough.

‘Never fear, lad, you’ll find no judgment here.’ He was laughing. Sir Francis is a ruddy and a rotund man, and his laugh is well matched to his person. ‘Been looking to unload Agnes for a while now, as a matter of fact. Helen and I ain’t particular as far as who to, and you’ll do just fine. Why don’t you come round Tuesday evening?’

This sort of impropriety I would ordinarily celebrate, but not when auditioning fathers-in-law. I declined.

The Pembrokes I enjoyed greatly, but the prospect of a half-dozen sisters-in-law was untenable. (One sister is quite enough.) I made it as far as a dinner, which was proceeding reasonably well, when the littlest one (Mary? Martha?) decided to be Mr Hyde. She jumped up on the table, thumped her chest with her tiny fists, and heaved a roasted pheasant at my head. That was that.

The Hammersmiths could have been the ticket, but their daughter was, I believe, replaced at infancy with a horse.

I could carry on and mention the Wellingtons, Blooms, and Chapmans — but my native discretion forbids it. Suffice it to say that the field was quickly emptied of players, and my options began to run low.

At the end of the day, in fact, the only real possibility was the Lancasters. They were rich, they were respectable and respected, and their daughter was beautiful. I will say that, whatever else I may lament — Vivien is very beautiful. Her hair is beaten gold, her eyes are a meteorological blue, her figure is — well, you have heard about her figure. It was her beauty I fell in love with first.

The dinner at which we met was unremarkable. It was not a private affair, but something of a party. I had contrived to procure myself an invitation on the grounds of my literary fame, and it seemed most of the guests had done the same. Whitley Pendergast was there, of course, as was Mr Collier, Mr Blakeney, Mr Morley, and Lord and Lady Whicher. (Whitley Pendergast is my rival and sworn enemy, and a terrible poet besides. The rest are literary personages of some reputation and indifferent talent. Benjamin Blakeney’s Barry the Bard I hope you have not read, and Edward Collier’s Penthesilea’s Progress I fear you have. I have forgotten what mangled offspring crawled from the pens of the others.) A few ministers of state rounded out the meal, but it would be in poor taste to mention them by name.*

I was seated between Pendergast and Vivien.

— But I have forgotten to finish setting the scene! Easton Arms, which is the Lancasters’ place in town, is a large town house in Belgravia furnished in the best and most modern taste. They are a very modern family, though very old in name. The art on the walls was unremarkable not in execution but in choice. If you were to close your eyes and name the six artists respectable and cultured persons of no particular taste ought to have on their walls, then you will have a very good idea of what hung in Easton Arms.* I haven’t a clue as to their names, as I do not keep up with such things. But you take my meaning.

Everything seemed gilt-edged. The mirrors, the frames of the paintings, the books on the shelves (I pulled several down and found the pages to be uncut) — even the curtains were trimmed with gold lace. The situation seemed promising. I prepared to be charming.

Читать дальше